by Shane Thomas

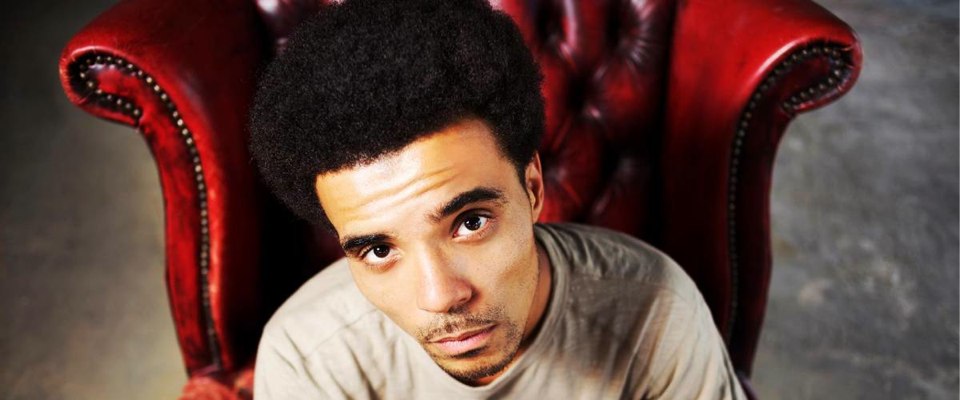

Back in 2011, Channel 4 had a season of programming, which they called their “Street Summer” season. A tokenistic nod to featuring the lives of working-class people, especially working-class people of colour? Possibly. However, it did feature some fascinating viewing. One of their programmes was the documentary, Life of Rhyme. It was my first encounter with the rapper, Akala.

Back in 2011, Channel 4 had a season of programming, which they called their “Street Summer” season. A tokenistic nod to featuring the lives of working-class people, especially working-class people of colour? Possibly. However, it did feature some fascinating viewing. One of their programmes was the documentary, Life of Rhyme. It was my first encounter with the rapper, Akala.

I subsequently went to YouTube, and discovered that Akala (born Kingslee Daley) is the brother of singer/rapper, Ms Dynamite, a former winner of the Mercury Music Prize, and a part of the soundtrack to my adolescence.

However, nepotism isn’t at play where Akala’s career is concerned. Read/watch any interview with him, and it’s clear that he’s not your average MC. One of my fellow contributors to Media Diversified, Lee Pinkerton penned an incisive piece on “the demise of conscious rap”. While it’s a fair assessment when you look at the milieu of popular hip-hop, Akala is someone who is the professional (rather than literal) progeny of acts such as Public Enemy[1].

Despite his four studio albums, Akala may be more familiar from his television appearances on programmes such as the BBC’s Free Speech or his two TEDxTalks. I confess that I’d heard his thoughts on societal aspects such as the music industry, the links between hip-hop and Shakespeare, as well as the true motivations for abolishing slavery in Britain and America, long before I had listened to any of his albums.

While it’s easy to be rhapsodic about his spoken word interactions, Akala is first and foremost a musician. Not only does much of his work come under the rubric of social commentary, but it’s framed from a historical context, bringing clarity to how kyriarchal structures are formed and ossified. Maybe the best example of this is one of his freestyles on Charlie Sloth’s show, the BBC Radio DJ.

While it’s easy to be rhapsodic about his spoken word interactions, Akala is first and foremost a musician. Not only does much of his work come under the rubric of social commentary, but it’s framed from a historical context, bringing clarity to how kyriarchal structures are formed and ossified. Maybe the best example of this is one of his freestyles on Charlie Sloth’s show, the BBC Radio DJ.

However, it should be stated that on Akala’s most recent record, The Thieves Banquet, there are a couple of tracks (Old Soul and One More Breath) where he appears to be taking a more introspective approach to his music. That said, the album’s title track, and the magnificent Maangamizi still give us a couple of history lessons.

I’m sure you have guessed by now that I am a huge fan of Akala’s[2], but that should never inoculate one from critique. He seems to excel when discoursing on topics such as racism, imperialism, and global history. However, I’m yet to hear him firmly address other intersecting forms of oppression such as sexism, transphobia or ableism in his body of work[3].

But given that Akala’s oeuvre over the past decade has shown constant progress, I see no reason why he won’t continue on the same upward swing. I think we are still yet to see the best from him.

And his best may not even come in the sphere of music. In 2012, he wrote an arresting short film, called Rage, starring Jimmy Akingbola. I hope it’s not the only time that he turns his creative eye to the arena of dramatised fiction.

Maybe it’s the genre-fiction fan in me, but in a parallel world I imagine Akala is plying his trade as a university lecturer, or maybe as a solicitor for the disenfranchised, much like the Laurence Fishburne characters in Higher Learning or Boyz N The Hood. He seems to believe that the key to a more equitable society is through comprehensive and unfettered access to knowledge.

That’s why I think that the artist Akala feels most redolent of is not Chuck D, Nina Simone or Bob Marley, but KRS-One. For “Knowledge Reigns Supreme Over Nearly Everyone”, read “Knowledge is Power”. Buy Akala’s music

[1] – Lowkey is another rapper whose work deviates from what we tend to hear on the radio. He has also been featured on these pages.

[2] – I try not to pay much mind to the online currency of Twitter followers, but I admit that – with the exception of Janet Mock – I don’t think I enjoyed gaining a follower more than Akala. If he ever reads this, sod’s law dictates that he’ll probably unfollow me.

[3] – For clarity’s sake, I’m not trying to accuse Akala of being bigoted towards those groups. Just at the time of writing, these issues haven’t been at the forefront of his work.

A mixed-race film graduate, Shane Thomas comes from Jamaican and Mauritian parentage. He has been blogging about sport since 2010 at the website for The Greatest Events in Sporting History. He is also a contributor to ‘Simply Read’, the blogging offshoot of the podcasting network, Simply Syndicated. A lover of sport, genre-fiction, and privilege checking, Shane can be found on Twitter, both at @TGEISH and @tokenbg (and yes, the handle does mean what you think it means).

Related articles

- Akala Music

- The ‘n’ word, and the demise of conscious rap (mediadiversified.org)

- The Lost Prophets: who does Hip Hop think it is? (mediadiversified.org)

- The Electric Lady (mediadiversified.org)

- Akala – Knowledge is Power. This is not just hip/hop rap, it’s liberation culture

- Akala – Double Think Lyrics

I was a huge Akala fan and when this piece first appeared on MD my take away was “I’m yet to hear him firmly address other intersecting forms of oppression such as sexism, transphobia or ableism in his body of work” and since then I have awaited the day Akala would address the above in his music and over a year later I am disappointed in him because he hasn’t addressed them at all. Maybe the occasional mention of sexism in a freestyle but that’s it. So Akala, the New Prophet = no, not really.

LikeLike

I will say in his defence that there are mentions of misogynoir in the song, ‘Maangamizi’, and he also touched on the topic in this interview back in 2013 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cyS0PmygoBA

Also, bar the odd freestyle from him, I don’t think he’s put out any music since this piece was published. Personally my main worry for artists is when their work ossifies oppression and makes things worse, so I’m reserving judgment for now, especially as he’s still relatively young, and I’d expect the quality of his output to get better as he gets older.

LikeLike