by Micah Yongo

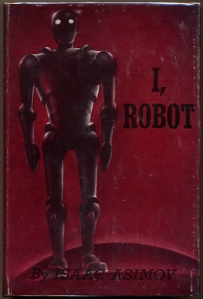

You need only cast a quick glance over the considerable career of someone like Isaac Asimov to note the prescient, directive power of science-fiction. The man who coined both the word and idea of robotics in his classic I, Robot and, in his 1964 article, Visit to the World’s Fair of 2014, foresaw everything from kitchen top coffee makers and microwave meals to satellite phones.

And then consider that Asimov’s predictions, as impressive as they were, cannot even be considered unusual amongst the sci-fi writing intelligentsia. Ray Bradbury prefigured the advent of earphones in his best known novel, Fahrenheit 451. Whilst HG Wells, as far back as 1899, was imagining automatic doors in The Sleeper Awakes. In fact, everything from bionic limbs (The Six Million Dollar Man) to credit cards (Edward Bellamy’s 1888 novel, Looking Backwards), to the now commonplace Skype-style video calling we all use and love has been prophesied one way or another by the heady imaginations of science-fiction. And that’s before we even get into how much of our everyday vernacular is co-opted from the oft quoted but rarely read (and yes, I have read it) George Orwell classic, 1984 – terms like ‘big brother,’ ‘doublethink’ ‘newspeak’ ‘thought-crime’ (none of which will trigger your present day spellchecker) were all coined in a book authored in 1949, a full two decades before CCTV made its first appearance in the 70s, and over half a century before Edward Snowden, Julian Assange and the pervasive surveillance culture that’s now so much a part of our world. We may as well call proponents of science-fiction ‘seers’ as well as writers, so often have their speculations foreshadowed, and in many cases shaped, the future reality. All that being said, at its heart sci-fi has always been about more than gadgets and technology. It’s a vehicle through which men and women have not just imagined the future, but also used those imaginations to critique the landscape of the present day (hence the often dystopian bent). The science-fiction genre is a domain of elaborate thought experiments. It means to do more than entertain, it seeks to show the world to us, one step removed, unveiled and refracted through the dark mirror of hyper-reality, and therefore beyond the apathy-inducing lens of what is familiar. It’s perhaps because of this that Ray Bradbury once called it,

“The most important literature in the history of the world, because it’s the history of ideas… central to everything we’ve ever done.”

And he’s kind of right. In generations long gone by our parables were hidden in aural traditions and fables, everything from Hans Christian Andersen, to Aesop, to Plato, Homer and back to the earliest cave drawings have carried their own polemic thrust. Our stories were ‘once upon a time’ then, hearkening back to fantastical histories in search of compass and roadmap for the realities of the present day. But since the forward-hurtling train the industrial revolution put us on, and the way technology has since quickened and enlarged the shifts between one generation and the next, the past has become a venerable though antiquated stranger, foggy and mysterious and hard to call to mind. In the words of bestselling science fiction novelist, William Gibson,

“It’s harder to imagine the past that went away than it is to imagine the future.”

All of which has meant one simple thing: the tales that now tell what’s wrong or right about how things are – our modern day myths, so to speak – no longer speak of what used to be, they envision what is still yet to come. And so it’s for this reason it’s somewhat alarming to find that for the most part science-fiction, at least until very recently, has been dominated by just one particular kind of imagined future. Gibson elaborates that,

“It seemed to me that mid-century mainstream American science-fiction had often been triumphalist and militaristic, a sort of folk propaganda for American exceptionalism. I was tired of America-as-the-future, the world as a white monoculture, the protagonist as a good guy from the middle class or above. I wanted there to be more elbow room.”

And more elbow room is exactly what certain parts of sci-fi, and afrofuturism in particular, has been trying to shoulder its way into for the last twenty years. Nnedi Okorafor, author of the award winning The Shadow Speaker (2007), notes that

“Science fiction is the only genre that enables African writers to envision a future from our African perspective.”

Which is a big deal. Because let’s face it, the co-opting of Africa’s future isn’t exactly a new or rare practice. Without getting into the hoary, knotty tangles of 19th & 20th century (French, Dutch, Belgian, Portuguese and British) colonialism, even since the many (apparent) liberations and independences of sub-Saharan Africa the narrative for what the continent is and ought to be has been written by everyone from Joseph Conrad (see his 1902 short novel Heart of Darkness, and Chinua Achebe’s critique of it) to Ernest Hemingway to CNN. With added emphasis on the latter, because the outsider’s perspective assumed by most western media is an issue, one acknowledged by Komla Dumor, a Ghanaian correspondent for the BBC, who recently lamented the media’s failure to recognise that any ‘expert’ analysis of Africa must come from its inhabitants, and not news organisations who’ve “[flown] in a correspondent to tell you what’s happening by looking out of [their] hotel window.” This kind of thing is why Kenyan film director Wanuri Kahiu says,

“we’ve never had a chance to talk about our own history, it’s always been written by other people.”

And this, also, is why afrofuturism is so important. The term was coined by the American author and critic, Mark Dery, in 1993, who correctly saw the genre as the perfect vehicle to narrate the African-American experience, an experience of those who were and are

“the descendants of alien abductees; [inhabiting] a sci-fi nightmare in which unseen but no less impassable force fields of intolerance frustrate their movements [whilst] official histories undo what has been done.”

Dery saw the subversive, outsider oeuvre of sci-fi as ripe for both “asserting [the African-Americans’] presence in the present and [making] clear they intend to stake their claim in the future.”

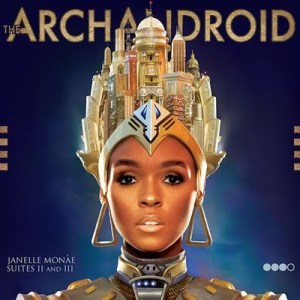

It’s this impetus to do so that Dery identified in the writings of Octavia Butler, Samuel R. Delaney and Charles Saunders, as well as spying incarnations of afrofuturism beyond literature in Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, Bernie Worrell’s Blacktronic Science and George Clinton’s Computer Games, a sort of technocultural funk meme that’s found continuance in the innovative sounds of Janelle Monae, Outkast and others. But today afrofuturism is broader than this, reaching beyond Dery’s initial remit to encompass writers from the continent of Africa as well as those of its diaspora, seeking to explore, in the words of artist and educator, Denenge Akpem, “what blackness could look like in the future”. And it’s this exploration that undergirds the genre’s import, and makes the work of writers like Nnedi Okorafor, Lauren Beukes, Sarah Lotz, Clifton Gachagua and Steve Barnes worth supporting even beyond the merits of their talent. Because science-fiction of all kinds – of which afrofuturism is one – has proven over and over again its ability to set the frame for how we envision the future, and as Zimbabwean author and publisher, Ivor Hartmann, puts it

“If you can’t see and relay an understandable vision of the future, your future will be co-opted by someone else’s vision, one that will not necessarily have your best interests at heart.”

______________________________________________________________________

Micah Yongo writes about creativity, literature, culture and film. He is part of the Writers of Colour collective and has been published at mediadiversified.org. When he isn’t busy writing articles he can be found, with knuckle to chin, at his blog Thoughthouse or else working on his own fiction writing. Micah tweets as @micahyongo.

______________________________________________________________________

Media Diversified is a 100% reader-funded, non-profit organisaton. Every donation is of great help and goes directly towards sustaining the organisation ![]()

Related articles

- Afrofuturism: Where Space, Pyramids and Politics collide (guardian.com)

- Where are the Black Women in Science Fiction? (www.mediadiversified.org)

- “Popular culture” is no longer a “marketplace of ideas.” (www.mediadiversified.org)

- Why Black Science Fiction is Essential for Our Children (brownmamas.com)

- Oh Come All Ye White Saviors (www.mediadiversified.org)

- ‘Afrofuturism’ on Display in Harlem (online.wsj.com)

- Doctor Who: The Day of the (White) Doctor (mediadiversified.org)

- In 1964, Isaac Asimov Imagined the World in 2014 – Rebecca J. Rosen – The Atlantic (theatlantic.com)

- “The Principles of Newspeak”

A wonderful article. I very much agree that Sci Fi is a reflection of how any culture can envision a future. I was just talking about this in regards to Battlestar Galactica. The modern remake and, indeed the original, heavily in envisions a Mormon sic fi epic. There are no people of any discernible culture beyond North American Asian and North American Northern European. This frightened me to no end, As Battlestar is a sic fi cosmology of the Earth itself. It takes me back to what Ms. Nichols’ said in her autobiography about Star Trek. “Always look to a vision of the future where skin colour is insignificant to the plot.” This is why she decided to stick with the show even during all the outward criticism.

My Best,

For More Articles About Sci-Fi and much much more check out the The Extremis Review. http://wp.me/43bYh

LikeLike

Brilliant article on the necessity of projection, to both critique and effect the present.

“It’s a vehicle through which men and women have not just imagined the future, but also used those imaginations to critique the landscape of the present day”

Well said.

LikeLike

Thanks, Akwesi.

LikeLike

This post reminds me of the comments Richard Pryor made after seeing the 70’s sci-fi pic Logan’s Run. “I didn’t like it. No niggers in it. Looks like white folks don’t plan for us to be here!”

LikeLike

Lol! Man did he have a way with words. But always knew how to make the point.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading this post. I also suggest looking at Alondra Nelson’s Introduction and Anna Everett’s “The Revolution Will Be Digitized: Afrocentricity and the Digital Public Sphere” in “Social Texts” (2002). Sound (DJ Spooky) and visual art, as well. Currently, there is an exhibition at The Studio Museum in Harlem called “The Shadows Took Shape” that explores afrofuturism.

LikeLike

Thanks. And thanks for the suggestions too. Visual art is a big part of this thing.

LikeLike

I hope that Blackness in the future will be ….. BLACK, not caramelized, not watered down, not so diluted that Black is no longer the essence.

LikeLike

Yeah, the hope is this genre of art will be what it’s been up to this point. A vehicle for black people to be author to our own images and ideas, a way to create the culture and identity we want to inhabit, rather than have it co-opted and created for us, as has often been the case in the past. Thanks for reading and sharing.

LikeLike

Excellent. Appreciate the Asimov and Orwell connections especially. Happy new year and here’s to future visions!

LikeLike

Thank you, Denenge! It’s very much appreciated.

LikeLike