by Chimene Suleyman Follow @chimenesuleyman

There is a painting in my parent’s house that my mother made. It is a self portrait; green eyes looking back between the black cloth of the headscarf painted around her face. It is a beautiful painting, carnal even. The assigned image on my phone for my father is a photograph taken from the same time as my mother’s painting. He sits straight, regal, the red chequered keffiyeh draped around his head. It was the 80s and we were living in Saudi Arabia. Their stories of this period in our life are as wild as they are affecting. My mother speaks of having to pretend to be my father’s “foreign” wife, denying her Turkish nationality so she would not be forced to fully comply with the strict rules assigned for Muslim women. She recalls the uncomfortable privileges she received when assuming this role of “white”, alongside her darker skinned girlfriends who would be whipped in shopping markets by men they didn’t know. The painting of her in such cloth is a nod to this point in her life; to her feminism, to her choice to wear and respect this headdress as well as the hardships of when it was not her decision alone. The image she presents in this painting – down to the item of clothing she is wearing – has become symbolic of the troublesome complexity of removing a part of your identity in order to salvage it elsewhere and, ultimately, what she reclaims of her ethnic legacy – earned and owned for herself.

For my father, the keffiyeh was an emblem of when he had once been a freedom fighter. The look on his face is tantamount to this. Perhaps unsurprisingly I grew up with a love for headdress; the meaningful and beautiful prints, the varied materials and shapes. That they remind me of my grandmother – her headscarves still my most valuable possession. They prompt a closeness between myself and her when I wear them beside her grave. Yet as a teen for many years I shied away from them, pushed to the back of the cupboard, the voice of friends and peers in my head; “You look like a gypsy,” went the jokes, “you’re dressed like a cleaner”. Imagine my surprise when I typed “headscarf” into a search engine and was faced predominantly with images of women not like my grandmother, but celebrities and models. Imagine the feeling when fashion magazines adopted them as their own. White women from America and the UK, the headdress wrapped around blonde hair as they tottered with accompanying designer handbag or shoe. Imagine how it felt. For me this was not progression. This was not a global community of cultural show-and-tell, but an insult. The message was that you would not be called names, told you looked “lower class”, inferior, if you didn’t look like me. At a respected and popular festival last summer a man with vicious scowl danced in the crowd; his face in black paint, his hands, a jumpsuit with a picture of Bob Marley, dreadlocks stitched to a Jamaican flag-print hat. Yet this indisputably aggressive and racist man was hard to spot, lost amongst the crowd of festival bindis and comedy afros, Day of the Dead headwear, Native American warbonnets, harem pants and ponchos. Near him marched a group in their own get-up – a recently resurrected and bizarre festival trend of British Raj fancy dress. We shook our heads at the man in black-face.

“Someone should tell the police to stop and search him,” a friend gloomily joked, “if people want to look black, they should know what it’s like to be treated as such.”

This quip was not only the comic-relief we very much needed, but of course a touching truth. How quick we are to slip on the once fashionable beaded moccasin, without walking a mile in them first. “I hate the stupid beards and skinny jeans,” Alex Proud predictably wrote of hipsters for The Telegraph in early January.

“I hate the ‘dirty burgers’ and the knowing appropriation of the 1980s icons that were never any good to begin with,”

I read on (the irony of the author not lost on me), hoping for the piece to say what other articles on the topic never do but of course wouldn’t.

“The real problem,” Proud wrote instead, “is hipsters themselves… who, in their quest to be different, have wound up virtually the same.”

Proud’s criticism – like much of the protest against hipsters and its current trends – is so misguided that its superficiality and privilege is equal to that of the trend it critiques. Beards, of course, are not worthy of hate. Neither are skin-tight trousers, burgers or that some people dress the same. That Proud’s greatest issue with appropriation is 80s pop-culture strikingly says it all, as once again cultural appropriation, neo-colonialism, misogyny and exclusionism have fallen off the list. What is hateful about hipster culture and its direction into the mainstream – pages of fashion magazines, the subject of TV, art, music – is the purposeful blind-spot it has for low income families and people of colour. Not only shifted from neighbourhoods, these original residents are further victims of abuse of stolen and polluted identity. It is the regular borrowing of ideas, life, food and cloth from outnumbered ethnicities to build careers and finance from, without ever crediting these minorities, that should be leaving us anxious and angry. Regions often torn apart first by the societies that now parade such traditions as though their own inheritance, the fine face of imperialism, is what should be clocking up words in mainstream media.

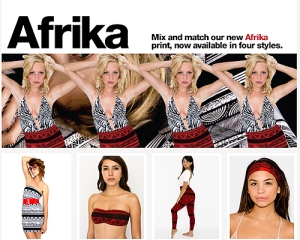

Sanaa Hamid’s artwork on fashion and cultural appropriation shows in only a handful of images everything that is wrong with it: the Middle Eastern man whose relationship with the keffiyeh supercedes image, “I am home, we are united” he says. This contrasted against the two-dimensional, “It’s only a scarf!” Of course when the keffiyeh became popular many of these street models would not have known, or perhaps cared, that the garment is symbolic of Middle Eastern politics and revolution. Likewise the ‘generic African print’ that has become so familiar in recent times on high street bought Kente cloth. Irrelevance for the individual meaning of these designs, some even to signify the death of a loved one. At other times the patterns have missed the point completely, meaning nothing at all as hundreds of African countries and tribes are clubbed together in this lazy distortion for fashion’s sake.

American Apparel’s advertising campaign might as well read,

“Africa: it’s a country, right?”

Amongst this all, as if the corruption of cultures were not enough, we are reminded that the way we carry our ancestry is wrong only bettered by the West. “If a Western person is accepted and applauded as ‘quirky’ and ‘cool’ for wearing a keffiyeh,” Sanaa Hamid said in an interview, “and a Middle Eastern is labeled a terrorist or ‘towelhead’ and dismissed as such, then no, that’s absolutely not okay.” Cultural appropriation is an understated yet poisonous racist devise. When keffiyehs became a fashion item it hurt my core more than any time I have been called “paki”. Here is why: name calling or misinformed beliefs of someone’s ethnicity, whilst hurtful, is a projection of the deluded and never a statement of the target. What is real are the customs that often begin as an unwanted spotlight on our “otherness” – our “grandmother’s headscarves” – before we are ready to fiercely declare this a symbol of our identification as immigrants, as children of immigrants, as targets of centuries of Western suspicion. What happens with appropriation is a suggestive scalping, a vogue bounty hanging from trendsetting bridle reins. It takes the crutch that we have pivoted our strengths around and bastardising it says, “here, let me have a go with that,” before losing our heritage under a pile of coats at a warehouse party. My father will often reminisce of moving to London as an immigrant in the 70s; a favourite anecdote of being unable to buy olive oil for his salads from any supermarket, told instead to try the pharmacy next door.

“Of course they will say Jamie Oliver invented it now,” my father says in front of the TV, sun-dried tomatoes, hummus, and olive bread a spectacle across the screen.

“It is only in the West,” my father speaks changing the channel, “that a white man will grab from your country and sell it back to you for more, as though you have never before seen it.”

This article was originally published on the wonderful Poejazzi website

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

_______________________________________________________

Media Diversified is a 100% reader-funded, non-profit organisaton. Every donation is of great help and goes directly towards sustaining the organisation

Related articles

- Iggy Azalea and a Culture of Appropriation (mediadiversified.org)

- African Culture Made in China (mediadiversified.org)

- Racism on the Runways (mediadiversified.org)

- NativeAppropriations.com

-

The Difference Between Cultural Exchange and Cultural Appropriation (everydayfeminism.com

- Should You Be Wearing That Keffiyeh? (animalnewyork.com)

- Another Case of Cultural Appropriation: Michelle Williams Poses as an American Indian (clutchmagonline.com)

I find articles of this kind to be rather depressing distraction from real issues. “Who cares” is the only valid response.

Everything comes from somewhere. Shall we give credit to the caveman who first wrapped an animal skin around his neck to keep it warm.

Shall we give credit to Charles Babbage every time someone makes new Facebook post?

Civilization is all about building blocks. This is simply another side of the culture “i should get credit/get paid because I was there first”

LikeLike

I am only just now reading this yet it is still fresh. What nourishing food for thought. Thank you.

LikeLike

I would say Caucasian non-European (Middle Easterners for example) who try to talk like they are oppressed “people of color” are engaging in cultural appropriation of the worst sort. Certainly Turks are Caucasian as are many Saudis, and even many of the Saudis white ‘progressives’ in the Western democracies describe (with patronizing pity) as “people of color” regard themselves as white and are often far more prejudiced towards nonwhite than Europeans.

Somewhere along the line over the past few decades the western democracies (particularly the English speaking ones) have by degrees redefined “white” and/or Caucasian such that it now typically is applied much more narrowly than it has been historically (historically the people of not just Europe but also the Middle East and North Africa have been considered “white”).

Many of the people who today speak with the pious self righteousness of martyrs about suffering “white privilege” would have been considered white until very recently. It’s a sort of Nordicism essentially, only instead of being promulgated by racist Nordic types on the extreme right it’s promulgated by self styled “progressives” on the left. It’s often to the point where it’s not unusual in some circles for Spaniards (you know, the people who invented the white master / black slave paradigm and subjugated most of the New World) to describe themselves as “marginalized people of color” – and receive sympathetic pats on the head from pasty Nordic types with a severely misplaced sense if guilt in return.

The term “people of color” is applied WAY too broadly, and charges of “racism” are made WAY too frivolously. It’s just… weird.

LikeLike

M.L. I don’t really agree with your position. You say “Caucasian non-European (Middle Easterners for example) who try to talk like they are oppressed “people of color” are engaging in cultural appropriation of the worst sort.” But surely it all depends entirely on context and the way in which those groups are treated where they live. In some places they will be the pivaledged majority and in some places an opressed minority or even an oppressed majority – witnes Egypt’s troubles. Racism isn’t primarily about colour or how different coloured people are classified but how people are treated as ‘other’ or not full citizens or not even fully human. Some of the worst genocides have been extreme versions of racism between people who look very much the same – driven by what has been termed “the vanity of small difference” or as Hitchens fampously called it in his Slate article the “narcissism of small difference”. The Holocaust, Ruanda, Pol Pot and the Balkans are all examples of extreme racism between similar cultures in which skin colour was not the main signifier. So it is absolutly legitimate for (for example) Turks to consider themselves oppressed in many Northern European countries simply becase many are oppressed. Likewise, in some circles Spaniards were until recently routinely dismissed by the white middle classes as ‘Dagos’ and are still characterised as such by racists. So while such racism might come and go withing various cultures and social milleu it would be wrong to dismiss the concerns of the victims as their lives might have been made impossible by their particular circumstances withing the socio-political sphere they find themselves. I do agree however that people who are not being targetted should not say they are, but that is a general point about honesty and not inventing victimisation; it’s not particular to racism.

LikeLike

The problem I have with cultural appropriation is the denial of it; not the fact of it. All culture comes from somewhere and it’s simply crazy to think that some modes of expression are ‘owned’ by a particular national or ethnic identity. I get furious when a blues song (say) by a black American is covered by a white artist and is announced as being ‘by’ the white artist yet I do not feel that ‘the blues’ should be forever ‘black’ music anymore than a celtic folk song should be ‘white’ music. Indeed, musicologists can trace so many links back and forth between cultures that it’s impossible to say what originated where. In fashion too, it’s annoying when a style or design goes unacknowledged and credit is taken for a pre-existing design from another culture. But it is surely the acknowledgement that is important, we should all be aware that we borrow artefacts from all cultures all the time and there’s nothing wrong with that so long as we don’t claim to have invented them ourselves.

LikeLike

“Someone should tell the police to stop and search him,” a friend gloomily joked, “if people want to look black, they should know what it’s like to be treated as such.”

“Of course they will say Jamie Oliver invented it now,” my father says in front of the TV, sun-dried tomatoes, hummus, and olive bread a spectacle across the screen.

“It is only in the West,” my father speaks changing the channel, “that a white man will grab from your country and sell it back to you for more, as though you have never before seen it.”

how one is treated and money , the crux of the matter

LikeLike