by Zoé Samudzi Follow @BabyWasu

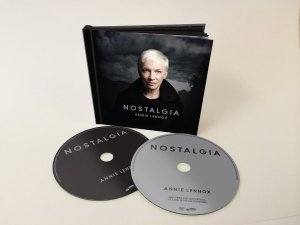

After her October interview with Tavis Smiley, I no longer think of Annie Lennox solely as the edgy, cool, and philanthropic Eurythmics frontwoman. I now see her as an embodiment of white ignorance. On her new album Nostalgia, Lennox covers “Strange Fruit,” a song popularised by Billie Holiday in 1939 that describes, vividly and hauntingly, a scene after the lynching of a black man. Lennox manages to describe her interpretation of the song without any mention of the lynching:

“Strange Fruit’ is a protest song and it was written before the Civil Rights movement actually got on its feet, got established. And because of what I’ve seen around the world, I know that this theme, this subject of violence and bigotry, hatred, violent acts of mankind against ourselves. This is a theme. It’s a human theme that has gone on for time immemorial. It’s expressed in all kinds of different ways, whether it be racism, whether it be domestic violence, whether it be warfare, or a terrorist act, or simply one person attacking another person in a separate incident. This is something that we as human beings have to deal with, it’s just going on 24/7. And as an observer of this violence, even as a child, I thought, why is this happening? So I’ve always had that sense of empathy and kind of outrage that we behave in this way. So a song like this, if I were to do a version of ‘Strange Fruit,’ I’d give the song honor and respect and I try to bring it back out into the world again and get an opportunity to talk about the subjects behind the songs as well.”

The Guardian hailed Lennox’s remake as a “brave reinterpretation.” This, of course, is in reference to her stylistic rendition of Billie Holiday’s blues vocals. The writer ignores Lennox’s very literal reinterpretation and whitewashed redefinition of the song. Lennox’s “Strange Fruit” stands in stark contrast to Holiday’s own understanding and description of her physical reaction each time she sang the song. As the story goes, the imagery was so sickening to her that she would vomit after every performance.

In her autobiography The Heart of a Woman, Maya Angelou recalls a discussion her son Guy had with Billie Holiday in 1957 about this very song:

On the night before [Holiday] was leaving New York, she told Guy she was going to sing “Strange Fruit” as her last song. We sat at the dining room table while Guy stood in the doorway.

Billie talked and sang in a hoarse, dry tone the well-known protest song. Her rasping voice and phrasing literally enchanted me. I saw the black bodies hanging from Southern trees. I saw the lynch victims’ blood glide from the leaves down the trunks and onto the roots.

Guy interrupted, “How can there be blood at the root?” I made a hard face and warned him, “Shut up, Guy, just listen.” Billie had continued under the interruption, her voice vibrating over harsh edges.

She painted a picture of a lovely land, pastoral and bucolic, then added eyes bulged and mouths twisted, onto the Southern landscape.

Guy broke into her song. “What’s a pastoral scene, Miss Holiday?” Billie looked up slowly and studied Guy for a second. Her face became cruel, and when she spoke her voice was scornful. “It means when the crackers are killing the niggers. It means when they take a little nigger like you and snatch off his nuts and shove them down his goddamn throat. That’s what it means.”

The thrust of rage repelled Guy and stunned me.

Billie continued, “That’s what they do. That’s a goddamn pastoral scene.” (Angelou, 1981, pp. 15-16)

Lennox’s artistic “reinterpretation” and subsequent narrative erasure is an illustration of white ignorance. White ignorance emerges from racialised epistemologies of ignorance. Epistemologies of ignorance pertain to not only knowing and not-knowing (epistemology is the branch of philosophy theorising about knowledge and its scope and nature), but also the “active reconstruction of one’s knowing” in a manner that may deliberately alter, obscure, or altogether erase the narratives of another (McHugh, nd). The epistemologies of wilful ignorance play a central role in whiteness’ epistemology of denial, that is the deliberate recreation of histories, events, sufferings and narratives of an other – in this case black people. These knowledges constitute a systematic social construction, “a political consequence of conflicting interest and structural apathies” (Proctor, 1995). It is in this context that whitewashing and cultural appropriation operate: it is a combination of white entitlement to cultural products, dominant narratives, and (re)definition of existence that these products become redefined at the expense of the cultural traditions from which they originate.

Lennox’s artistic “reinterpretation” and subsequent narrative erasure is an illustration of white ignorance. White ignorance emerges from racialised epistemologies of ignorance. Epistemologies of ignorance pertain to not only knowing and not-knowing (epistemology is the branch of philosophy theorising about knowledge and its scope and nature), but also the “active reconstruction of one’s knowing” in a manner that may deliberately alter, obscure, or altogether erase the narratives of another (McHugh, nd). The epistemologies of wilful ignorance play a central role in whiteness’ epistemology of denial, that is the deliberate recreation of histories, events, sufferings and narratives of an other – in this case black people. These knowledges constitute a systematic social construction, “a political consequence of conflicting interest and structural apathies” (Proctor, 1995). It is in this context that whitewashing and cultural appropriation operate: it is a combination of white entitlement to cultural products, dominant narratives, and (re)definition of existence that these products become redefined at the expense of the cultural traditions from which they originate.

In examining these epistemologies of ignorance as a product of the structures and ideologies of whiteness, we see the constructions or erasure of narratives in order to reproduce dominant racialised worldviews. Ignorance and dominance are inextricably linked in the context of whiteness because the forced perpetuation of particular worldviews can be construed as the “refusal of multiple ways of knowing,” (May, 2006). Charles Mills discusses the concept of white ignorance by stating that it emerges from white supremacy and the tacit agreement of those invested in whiteness to fundamentally misrepresent the world and to subordinate all other narratives pertaining to knowing and understanding (2008).

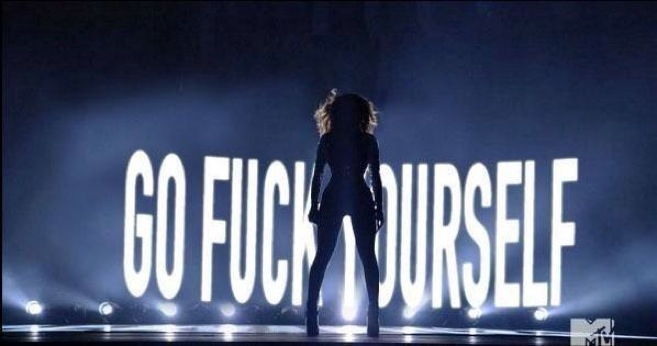

In this light, Annie Lennox’s statements, though reprehensible, make sense. Her feminism and conceptualisation of the world are both created from and centred on the preservation of these epistemologies of whiteness and the necessary ignorance and denial therein. Lennox had previously criticised the sexualisation of women in the music industry “from a perspective of a woman that’s had children.” She went on to comment about Beyoncé in the context of her own understandings of feminism:

“I was being asked about Beyoncé in the context of feminism, and I was thinking at the time about very impactful feminists that have dedicated their lives to the movement of liberating women and supporting women at the grass roots, and I was saying, ‘well that’s one end of the spectrum, and then you have the other end of the spectrum…Listen, twerking is not feminism. That’s what I’m referring to. It’s not—it’s not liberating, it’s not empowering. It’s a sexual thing that you’re doing on a stage; it doesn’t empower you. That’s my feeling about it.”

The reduction of Beyoncé’s dancing, sexual expression, and identification with feminism to mere “twerking” seems to come from a highly prescriptive and limited understanding of what feminism is. Lennox’s feminism is one where other cultural histories, aesthetics and performances are denigrated. Even in appropriating black female sexuality and using black women’s bodies as literal performance props, Miley Cyrus has largely escaped the feminist condemnation squarely aimed at black women. Mainstream white feminism’s entrenchment in white ignorance can render white women unable and/or unwilling to create space in feminism for nuanced and alternative understandings of women’s sexual agency and racialised experiences, and it led Annie Lennox to overlook the history of racialised violence and oppression that inflects Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” Even the line “black bodies swinging in the southern breeze” didn’t jar Lennox out of her wilful and racialised ignorance. Lennox’s refusal to recognise the historical context and significance of the song and to meaningfully engage with black history illustrates some of the tensions that continue to shape many of the interactions between intersectional feminism/womanism and white-centred mainstream feminism. The imbrication of whiteness in feminist movements perpetuates the notion that feminism is an exclusive playground, the entrance to which is protected fervently by white western middle-class cisgender heterosexual and able-bodied gatekeepers.

It is crucial to understand that this ignorance is not innocuous. It has far-reaching implications for what we collectively understand and hold to be true. Lennox’s treatment of “Strange Fruit” was not simply an unknowing misrepresentation of a song: it is a part of wider structures of social amnesia that systematically erase resistant narratives and counter-discourses, an Orwellian forgetting of something we once knew to be true (Wylie, 2008). This form of erasure has been called epistemic violence because the systematic suppression of narratives of oppressed people is an injustice that exists as a form of violence in itself. Not only is this erasure a form of epistemic violence, but the silence on the matters of race, sexuality, and gender-based violence serves as a mode of complicity with the dominant and oppressive status quo. My intention in drawing attention to Annie Lennox’s treatment of “Strange Fruit” is to show one way in which white feminism can be complicit with epistemic violence and injustices.

What is especially challenging about these forms of epistemic ignorance is that they cannot be informed and ‘corrected’ by fact alone. Stories of racism, news clippings of trans female murders, discussions of demographic-specific vulnerabilities, and constant critique by those who are the subjects of structural inequalities would be more than sufficient to establish ‘truth’. It is only through a conscientious process of acknowledgement and engagement that meaningful change can come about: an important albeit difficult conscientious process not wholly unlike the one that occurred at the Women in Africa and in the African Diaspora conference in Nigeria in July 1992. But what does this engagement look like? What are the particular processes through which we can mitigate these often overlapping epistemologies of ignorance? Admittedly, these are complex manifestations of deeply entrenched hegemonic histories and ideologies. I certainly don’t have all the answers, but perhaps if we can begin to describe the workings and varied effects of these oppressive phenomena, we can begin to bring them out of the shadows, name them, and work together to devise strategies for building and sustaining counter-narratives, discourses, and new epistemic traditions.

References

McHugh, N. (nd). Telling her own truth: June Jordan, standard english and the epistemology of ignorance.

Proctor, R.N., 1995. Cancer wars. New York: Basic Books.

May, V.M., “Trauma in paradise: wilful and strategic ignorance in Cereus Blooms at Night. Hypatia, 21(3), 107-135.

Mills, C.W., 2008. White ignorance. In: R.N. Proctor and L. Schiebinger, eds. Agnotology: the making and unmaking of ignorance. Stanford University Press, 230-249.

Wylie, A., 2008. Mapping ignorance in archaeology: the advantages of historical hindsight. In: R.N. Proctor and L. Schiebinger, eds. Agnotology: the making and unmaking of ignorance. Stanford University Press, 183-205.

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Zoé Samudzi, a first-generation American of Zimbabwean origin, has recently finished a masters degree in community development at the London School of Economics. She is dedicated to taking a critical and intersectional approach to all topics of interest, particularly in gender politics and public health discourse. You can catch her tweeting at @BabyWasu

This article was commissioned for our academic experimental space for long form writing curated and edited by Yasmin Gunaratnam. A space for provocative and engaging writing from any academic discipline.

The comments here are much better than the article, unfortunately. It’s quite poor that the article is premised on Lennox singing this song and not discussing lynching when she has, in fact, grounded the song in its birth horror multiple times in other interviews and on the record notes. And that’s only the start..

LikeLike

Great article except for the Beyoncé part. Having your PR person pen a letter doesn’t make you a feminist.

LikeLike

Great article! Will be searching out your sources for further reading tonight. Thanks

LikeLike

Hmmm, no.

LikeLike

Here’s another interesting art-critical feminist/anti-racist failure piece about how Annie Lennox is racist cause she sang Strange Fruit, and is therefore engaged in the crime of ‘cultural appropriation’, and also white ignorance and black historical erasure cause she didn’t use the phrase ‘lynching’ when she talked about it on the Tavis Smiley show, although she had talked about lynching in other interviews.

Never anybody mind that Strange Fruit the song was actually written by a white Jew, and that Billie Holiday literally stole the song and claimed she wrote it in her biography.

I personally might argue that Billie Holiday made that song her own, that the song holds a sacrosanct place in American culture. Therefore the song is a special case and white people better have a damn good reason for doing it.

But it’s stupid to go off about ‘white ignorance’, and appropriation when your own self is too ignorant to look up who wrote the damn song in the first place. So much for that Master’s Degree…

LikeLike

A bit harsh, perhaps, but you’re absolutely right.

LikeLike

It’s difficult to read comments like this because I ask, is this person unable to read? Do they have reading comprehension problems? Or, are they purposely twisting the crux of the commentary to suit their own ends?

Reread the second paragraph of the commentary. The basis for the critique of Lennox is based on her omitting the visceral evil that is at the heart of the song. Cultural appropriation happens when you recontextualize that which belongs to “The Other” and strip it of its essence – which is EXACTLY what Lennox did. The same cannot be said of Abel Meeropol, the man who wrote the lyrics. I am sure that if he was alive, his explanation for penning the lyrics would be would be VASTLY different than Lennox’s and would be inclusive of the photograph of a lynching that spurred him to write the lyrics.

So, Annie Lennox and White ignorance? Well, yes, in that her ignorance is willful. No, in that it is White privilege that allows her to omit the song’s essence, as with an admission, it then becomes difficult to walk through Western society without wincing at nearly every turn.

Is it racist? Of course! Perhaps you and yours have forgotten that Western civilization as we know it was built by forcibly taking the land of people of color and appropriating their cultures. To do so, White people had to develop a sense primacy – no matter how false – when viewing people not like them; that it is THEY who are the pinnacle of their god’s creation and that all other people are lesser forms of this creation… PRIMACY.

To justify their theft of other peoples’ lands they gave the excuse that these people, people of color, were and remain inferior to them; less intelligent, soulless, primitive, incapable of meeting the requirements SET BY WHITE PEOPLE of what “civil,” “civilization,” and “civility” mean.

Lennox’s reducing Beyonce to a “twerker” is illustrative of her establishing primacy over The Other – as if Lennox never donned period costumes and pranced around on stage shaking her ass singing… as if “Sweet Dreams” was something more than an emo, synth period, pop song) . Oh, but I forgot, those actions and songs when performed by Lennox are, “art.”

Sure.

As bell hooks has asked for forever and a day, why must there be “Black feminism? Answer: to establish and maintain the primacy of feminist theory and philosophy when espoused by White women.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your excellent piece. It’s given me lots of information and clarified things in such a way enable me to do much better work on many fronts. I hope that everyone reads it.

I once had a white student in my voice studio who told me at the end of a lesson that she wanted desperately to work on “Strange Fruit”. She was passionate, young and filled with good intentions. I praised her for her musical taste and ambition and her passion for social justice. Then I asked her if she’d ever witnessed a young black man being lynched or knew anyone who had. She gave me a confused look and said no. I told her to go home and think very hard about this because unless she could feel every aspect of that experience to the core of every bit of DNA in her body, she shouldn’t sing the piece. She quit lessons not long after that.

LikeLike

You could have been more supportive and suggested that by studying/ performing the song combined with learning more about black lynchings, slavery, and abuse that it could be a way in which she could feel every aspect of that experience to the core of every bit of DNA in her body. Rather than the other way around.

Studying music can be a way of learning about humanity, rather than a means of pure self expression. If you have personally witnessed a black lynching you could have have conveyed those experiences to her to help her developed a deeper understanding of the song. Maybe you could have aranged for her to meet some people in the community that have have witness these lynchings. You are a teacher after all. How many people today under the age of 30 have witnessed black lynchings or know someone who has? Ideally this should be zero as generations pass. Should the song then cease to be sung?

LikeLike

So, Catherine, in regard to the comments above, would you also have crushed the compassionate response of the Jewish guy who wrote the song? Because you might have prevented it from ever being written. Art is about taking leaps. Inequality is terrible, but so is killing the creative spirit in your students.

LikeLike

Anybody over 5 has witnessed a lynching: it is just not defined so. The recent spate of police murders, and the brutal carceral state are a testament to modernized manifestations of lynching. Don’t know if you are privy to the war-related lynchings that take place far away from our safe spots. The languages we use and its framing can make a whole lot of difference.

LikeLike

How refreshing to read these thoughtful comments without the usual diatribes

It was almost as enlightening as the very interesting article itself.

LikeLike

I feel this is some very misguided anger. Lennox may not be as specific as we would like her to be, but to say she “whitewashes” would be a rhetorical distortion. She is clearly making a statement against intolerance and hatred. And if the song is a good song, she should be applauded. If she isn’t as articulate as we would like her to be when someone had a camera on her and asked her about it, well, not many of us are Maya Angelou (who, as a writer and not an on-camera personality, actually got a little more time to craft her own description.) Let’s stay focused and save our anger for the real villains.

LikeLike

Also, whilst racism is very well known, there’s plenty of violence in women’s experience such as the Irish homes for fallen women or the English mental asylums where child and female rape victims were locked away without trial, often for life, where they were subject to various physical and drug experiments, raped by guards, beaten , starved and electroshocked whilst being worked as slave labour. The last of these ‘homes’ or cocentration camps as the UN called them, only shut down in 1995. Pain can be felt by many races and when it comes to social injustice, being raped because your black or because you’re a womeh doesn’t lessen the pain to either.

LikeLike

I’m not a big fan of Annie Lennox but I’m not sure the criticism in this article is correct. Lennox doesn’t say anywhere that the song isn’t about racist murder. She says the song’s theme is “violence and bigotry, hatred, violent acts of mankind against ourselves.” You can’t dispute any of that. Racism is of course a particular and particularly toxic form of “violence and bigotry, hatred, violent acts of mankind against ourselves”, but just because Lennox doesn’t emphasise this particularity doesn’t mean she is hiding it. In fact, she goes on to say “It’s expressed in all kinds of different ways, whether it be racism, whether it be domestic violence.” So she’s making the point that the wickedness of racist violence is part of a more universal wickedness. Far from being ignorant, she is making a point that is at the heart of the civil rights message. The white racist considers violence against blacks not to be violence because he doesn’t consider black people to be fully human. Just as mysogenists justify violence against women on the premise that women are inferior. Lennox says that violence against black people, against women, is simply violence and unacceptable as such. So she’s singing from the same book as Dr. King and the civil rights movement in general. Indeed, you might wonder how her interview would read if she were to highlight that “Strange Fruit” was about lynching. To me it would seem strange; my reaction would be “duh – no kidding.” The subject of the song is so well known by now that it can be taken as read, and Lennox probably took it as read. Far from showing ignorance of the song’s meaning Lennox probably is so familiar with it that drawing attention to it doesn’t cross her mind. Where I do think she is a little lame though is that recently there have been many high profile murders of black men by white policemen or security guards which have gone unpunished, most recently near St Louis but also the awful shooting of Treyvon Martin – which went unpunished due to the appalling, disgusting and heinous “stand your ground” legislation – and strangling of Eric Garner. If you want to show why Strange Fruit is still relevant today you don’t need generalities. The fact that Lennox didn’t mention these events in connection with singing the song today was air brushed and PC.

LikeLike

Kanye West bastardised ‘Strange Fruit’ for ‘Blood on the Leaves’ to describe his own sordid personal life, and nobody criticised him for it at all.

Annie Lennox may have avoided the topic of lynching in interviews, but she is clearly aware of the song’s origin. How could you not be! There is no ignorance here. Tact maybe. Widening the song’s core to encompass all violent crimes committed by humanity is hardly offensive. How could she channel Billie Holiday’s visceral reaction without widening the subject to include her own experience?

Do not punish people for empathy. The sentiment of this article is that one ethnic group ought not to be able to express another – can you really advocate that kind of weird cultural separatism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d agree that Kanye West’s narcissistic appropriation of “Strange Fruit” is problematic, and that it’s obvious nonsense to suggest that West’s blackness grants him some ownership of the song that extends to such use of it. That being said, West actually *did* cop some flack for “Blood on the Leaves”. The trouble with all this is that “Yeezus” was a solid contender for the best album of 2013, despite containing plenty of misogyny and homophobia in addition to the tasteless “Strange Fruit” sample. It’d be great if less obnoxious people were making records anywhere near as brilliant as “Yeezus”, but very few are.

I don’t think anyone gets to declare that “widening” the focus of “Strange Fruit” is “hardly offensive”. Lennox’s approach to both feminism and human rights is grounded in a universalizing tradition that is at once compassionate and well-intentioned, but also dangerous in its tendency to elide differences in the experiences of different groups. Highlighting such differences isn’t just “weird cultural separatism”; it’s giving voice to lived history. So while Lennox’s statement on “Strange Fruit” certainly isn’t “reprehensible”, as this author histrionically asserts, it does carry potential for causing inadvertent offense–and it’s entirely reasonable for the author to make *that* point.

I’m actually not clear on whether the author is arguing (preposterously) that Lennox is ignorant or unaware of the specific subject matter of “Strange Fruit”, or rather (more reasonably) that Lennox is aware of this subject matter but gave it insufficient attention in her generalizing statement about the song. Certainly the claim that Lennox displays a willful “refusal to recognise the historical context and significance” of “Strange Fruit” is odd; her answer to Smiley begins precisely by placing the song in its pre-Civil Rights-movement context, and her comments elsewhere and in the liner notes go into further detail about the subject of lynching. To be honest, I imagine Lennox was taking for granted that everyone knows what the song is depicting. At the same time, it’s fair to say Lennox’s statement failed to “meaningfully engage with black history” in this case, and fair to argue that any statement about “Strange Fruit” should do so.

LikeLike

Respectfully, have you even listened to Yeezus? There’s no homophobic lyricism in the least, in fact West has received plaudits for being an early ally of the gay community and speaking out against homophobia in a homophobic hip-hop community in 2004 when it was not receptive as it is today. Seems to be a lot of ignorance when it comes to West’s music actually, considering most, you included, seem to criticize him based on his public persona rather than his musicality.

LikeLike

There’s plenty to be said here, regarding both Annie Lennox and the article itself. Lennox has mentioned the depiction of lynching in “Strange Fruit” in multiple interviews and in the liner notes to her record; her discussion of lynching as an instance of human brutality in general risks implying questionable equivalencies, but is obviously well intentioned. She’s also voiced reservations about the sexualization of many female pop stars (irrespective of race), and has hardly singled out Beyonce in this regard. Lennox seems to miss the feminist significance of Beyonce’s assertion of black female sexuality and desirability–but this doesn’t change the fact that Bey’s power as a cultural icon is troublingly conditional on her largely conventional attractiveness.

This article is essentially a rewrite of a click-bait Gawker post from a few weeks back. It adds only the exasperating pretentiousness of much Anglo-American humanities writing: an intellectually facile critique of a trivial pop-culture moment is delivered in the tortured argot of critical theory, and falsely presented as an activist contribution toward social change. The last paragraph is laughable both for its unearned grandiosity and its hedging, hand-waving emptiness: “… what does this engagement look like? … perhaps if we can begin to describe the workings … of these oppressive phenomena, we can begin to … work together to devise strategies for building and sustaining … new epistemic traditions.” Such piffle offers much less to actual marginalized people than it does to an author’s parasitic self-regard.

LikeLike

Yes, exactly!

LikeLike

Couldn’t agree with you more: the pitiful, incredibly immobilizing grandiosity and pomposity of much of American memes (had one teacher like that who dismissed off anything that did not comport with his self-absorbed imagination) only serves to make the spaces of social change that much harder to grasp. The marginalized other cannot wait for that endpoint of critical theory that resolves all the dilemmas.

LikeLike

This article is mightily problematic. Though there are some incredible points, we can’t claim that Strange Fruit is a piece explicitly and totally owned by Black people. Firstly (and controversially) I propose that that’s just not how art works. People reinterpret and just because Lennox is a white woman it does not mean she has no right to inflect her understanding of the pain of the world into the song.

The second point is factual: Strange Fruit was written by a white man. Plain and simple. Yes, it’s a black anthem and speaks of black issues and may be sung best by black people. But those words, the poem, the imagery, stem from the bleeding veins of a Jewish man who could stand the horrors of lynching. If we continue to crucify everyone for co-opting our struggles, we may just miss out on some amazing, wonderful change.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am so glad someone left this comment.

For the author to not confront, and then tackle, the plain fact that a white man wrote the song — however problematic this may be to the overall argument — is a simply extraordinary oversight, whether wilful or accidental. Unfortunately this factual absence fatally weakens the whole piece. There are, I’d agree, some excellent points made though.

LikeLike

Another writer on the site addressed that in this piece Strange Stains in Ferguson http://wp.me/p3HucV-ds he rewrote strange fruit in the context of police shootings. With only 2000 words the author was hard pressed to also fit in how there was also a relationship between Jewish songwriters and black musicians because of industry domination but also because of the ways oppressions overlapped.

LikeLike

Great! Thanks for the link.

LikeLike

Strange Fruit was written by a white man, yes, but for and about a definitive black experience. To wit, it is as “black” as anything out there. Yes, its lessons are paradigmatic if not transcendent, that is indisputable, so I suspect. We would do well to heed the message embedded in the art form, not just for blacks but for humanity as a whole.

LikeLike

Annie Lennox did mention the lynchings in other interviews, like this one:

http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-29129566

LikeLike

oh now this is interesting….

LikeLike