by Rajeev Balasubramanyam Follow @Rajeevbalasu

George Orwell called Rudyard Kipling ‘the prophet of British imperialism… morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting.’ And yet eighty years after Kipling’s death, Disney’s adaption of his Jungle Books (itself a remake of the 1967 original) has become a global success and the second highest grossing film of this month. Have we really progressed so little, or has director Jon Favreau succeeded in eliminating the story’s imperialist undertones?

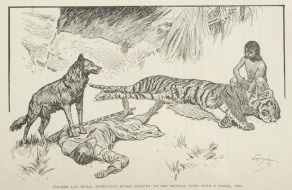

Kipling, who lived in India till the age of six then returned to Britain at sixteen, suffered from that most modern of maladies ― the identity crisis. About his return he said, ‘… my English years fell away, nor ever, I think, came back in full strength.’ Like Kipling, the feral boy, Mowgli, is never sure whether he is animal or man. His closest friends are the wolves who raise him, Bagheera, a panther, and Baloo the bear. His enemies are Shere Khan, a tiger, and the monkeys about whom Baloo says, ‘We do not drink where the monkeys drink; we do not go where the monkeys go; we do not hunt where they hunt; we do not die where they die.’

Kipling, who lived in India till the age of six then returned to Britain at sixteen, suffered from that most modern of maladies ― the identity crisis. About his return he said, ‘… my English years fell away, nor ever, I think, came back in full strength.’ Like Kipling, the feral boy, Mowgli, is never sure whether he is animal or man. His closest friends are the wolves who raise him, Bagheera, a panther, and Baloo the bear. His enemies are Shere Khan, a tiger, and the monkeys about whom Baloo says, ‘We do not drink where the monkeys drink; we do not go where the monkeys go; we do not hunt where they hunt; we do not die where they die.’

In the context of India, the monkeys are highly suggestive of untouchables, though in the 1967 Disney adaptation their leader, King Louie, is presented as a gross caricature of an African-American, race becoming a substitute for caste in a possibly unconscious act of social translation.

In Kipling’s original, racism is most apparent when it comes to ‘men’, of whom we have two types: the English colonialists and the Indian villagers. The villagers are backward and ignorant, threatening to burn Mowgli’s parents to death for siring a ‘devil child’ (ironically, Kipling describes the natives in ‘The White Man’s Burden’ in almost exactly the same way). They run for sanctuary to the British, who, ‘it is said… govern all the land, and do not suffer people to burn or beat each other without witnesses.’

Kipling’s Mowgli is himself culturally more wolf than Indian, and he hates the villagers so much that he ends up exhorting the elephants to trample the village of out of existence. Like Mowgli, Kipling’s boarding school experience meant that he was torn from his parents at an early age, something he describes in terms equally as terrifying as those he uses for the jungle. Kipling’s jungle, unlike Disney’s, is not sanitised, but nonetheless reads like a child’s fantasy refuge and as a vehicle for the writer to express his very real love of India without having to acknowledge the equal humanity of Indians themselves.

Favreau’s adaptation for a worldwide audience escapes these very obvious pitfalls by casting Christopher Walken, who sounds like a vaudeville imitation of the Godfather, as the voice of King Louie, thereby removing the undertone of internalised racism from ‘I Wanna Be Like You’, and by almost entirely eliminating the presence of humans. The 1967 version ends with Mowgli leaving the jungle in pursuit of a beguiling village girl, but in Favreau’s this has been expunged and Mowgli remains in the jungle. We see the only villagers for a few seconds in a series of nighttime montages ― silhouetted, surreal images in front of a fiery background that, in contrast to the jungle, looks nowhere near real.

While the CGI-rendered jungle looks very real, it does not feel much like India, or indeed any single place. Favreau’s jungle is more of a global one, resembling a composite of familiar scenes from The Lion King then Avatar, and then perhaps Arizona, or Rajasthan, or the Sahara. Anything that smacks of cultural specificity has been eliminated, including Colonel Hathi the elephant, who in the 1967 version was an amusing stereotype of a British colonial officer, and the four vultures based on the Beatles. Walken’s King Louie voice does not signify an Italian-American but instead references gangster films, a global rather than specially American signifier.

While the CGI-rendered jungle looks very real, it does not feel much like India, or indeed any single place. Favreau’s jungle is more of a global one, resembling a composite of familiar scenes from The Lion King then Avatar, and then perhaps Arizona, or Rajasthan, or the Sahara. Anything that smacks of cultural specificity has been eliminated, including Colonel Hathi the elephant, who in the 1967 version was an amusing stereotype of a British colonial officer, and the four vultures based on the Beatles. Walken’s King Louie voice does not signify an Italian-American but instead references gangster films, a global rather than specially American signifier.

By contrast, Mowgli, played by Neel Sethi from New York City, talks and behaves exactly like what he is ― a twelve-year-old Indian American. His Mowgli is far less fierce and defiant than either the Mowgli of the books or of the 1967 version, appearing less a product of the jungle (or of an abusive boarding school) than a suburban American basement complete with litres of soda and a PlayStation, in the manner of all middle-class post-globalisation kids.

There are still divisions within the animals of the jungle, but they now follow the fault-lines of the global middle-class imagination rather than a colonial Indian one. Shere Khan, who remains the only character with a Muslim-sounding name, is still the rogue threat, marauding across our screens in defiance of law and harmony. The monkeys are still the dregs of society, but are now deracinated, non-specific. The most unexpected change is that Kaa, voiced by Scarlett Johansson, suddenly resembles a sexual predator, though this is admittedly another ever-present danger in the postmodern suburban psyche.

As a result, despite boasting an ethnically diverse cast, there is no actual diversity within Favreau’s The Jungle Book because there are no actual identities. In 1892 Kipling was almost certainly aware of the Sanskrit fables of the Panchatantra and Hitopadesha, and appropriated these fables of talking animals for his colonial context, while in 1967 Disney did the same to him. But Favreau’s movie takes it one step further, using CGI to erase even the notion of context, trampling not a village but an entire country out of existence and replacing it with one of his own invention. This is global corporate technological colonialism, and it is total.

In Kipling’s books we never actually see the British, and in Favreau’s adaptation we never see the hidden hand of production… until the final credits when our on-screen world is shrunk to a three-dimensional ‘stage’ surrounded by a plush blue curtain. None of what you thought was real is real, is the message. It is we who own this world, not you.

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Rajeev Balasubramanyam is an award-winning novelist, and the author of In Beautiful Disguises (Bloomsbury), The Dreamer (Harper Collins), and Starstruck, which will be published in May by the new multi-mediate digital platform thepigeonhole.com. He is the winner of the Betty Trask Prize, the Ian St. James Award, and the Clarissa Luard award, and was longlisted for the Guardian First Fiction Prize. He is a graduate of Oxford and Cambridge universities, and has a PhD in Black British literature. He is currently a fellow of the Hemera Foundation for writers and artists with a meditation practice. You can sign up for Starstruck here and follow him on Twitter @Rajeevbalasu

If you enjoyed reading this article, help us continue to provide more! Media Diversified is 100% reader-funded – you can subscribe for as little as £5 per month here

The frightening thing about Kipling is that he isn’t ‘morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting.’ A great writer in verse and prose, his warped morality is served by his enormous artistic skills. Alongside Ezra Pound he is one of the writers who raises the question of whether great talents misused can ever be forgiven.

LikeLike

Great post

Gmail

Thanks for sharing https://mail.google.com

LikeLike

Interesting insights, thanks for sharing!

LikeLike