In a fascinating essay, Ronald Kuykendall discusses the “right wing wave”, and how it relates to white identity politics, the history of factions in the two-party system in in the USA, and the backlash to the Obama presidency

It is obvious and undeniable that in the United States the Republican Party is attractive to reactionaries, racists, those with fascist tendencies, white nationalists, and, in general, extremists’ right-wing elements. Moreover, the magnetism of the Republican Party to these elements has little, if anything, to do with the wave of right-wing populism, white nationalism, and Euroscepticism sweeping over the West.

The right-wing ideological wave encapsulating Europe has been attributed to the 2008 Great Recession that created fears of white economic displacement along with political disaffection with establishment politicians and parties. The fear and anxiety were then transferred to issues of immigration, cultural liberalization, and perceived threats to national sovereignty and security by right-wing groups, politicians, and political parties. They seized the opportunity and took advantage of this mood to create a narrative which served to explain the crisis not as a failure of capitalism and neoliberal government complicity, but as a consequence of liberalization which opened the door to mass immigration, racial diversity, and cultural tolerance which then threatened white hegemony and white privilege.

However, in the American context, the makeup of the Republican Party and the consequent election of Donald Trump is not an American version of what we see in Europe. Rather the political disposition of the Republican Party represents an old political faction within the white American ruling class establishment. This old political faction once belonged to the Democratic Party but migrated to the Republican Party because Depression Era New Deal Democrats had become both governmentally and racially more liberal. This takeover of the Republican Party is a result of an intra-class political struggle, and this struggle extends back to the very founding and establishment of the American government.

“This did not mean that being antislavery meant being pro-Black or anti-racist. To the contrary, the antislavery faction opposed slavery as a mode of production and a system of labor but still believed in the racialized class system in which whites were superior.”

From its inception, the dominant political class that emerged during the founding and establishment of what would become the United States and the American government was white, wealthy, male, and racist; they were successful plantation owners, slaveholders, large land speculators, bondholders, real estate investors, merchants, bankers, and lawyers with considerable experience in politics and government. As a political class, their goal was to overthrow the British colonial system and institute a new system of government reflecting their political and socio-economic interests. These individuals organized and financed the American Revolution and set up the first American government under the Articles of Confederation. And when the Articles proved to be problematic, these individuals arranged and controlled the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the constitutional ratification process, and positions in the new government to guarantee that it reflect their political and socio-economic interests.

However, within this political class have existed two factions competing for national political hegemony. These two factions emerged at the very beginning of the American government representing regional groups within the white American ruling class – north and south, manufacturing and agriculture, antislavery and proslavery – that would vie for political control but nonetheless shared a fundamental belief in classical liberalism, capitalism, republicanism, inegalitarianism, and white supremacy. However, this did not mean that being antislavery meant being pro-Black or anti-racist. To the contrary, the antislavery faction opposed slavery as a mode of production and a system of labor but still believed in the racialized class system in which whites were superior.

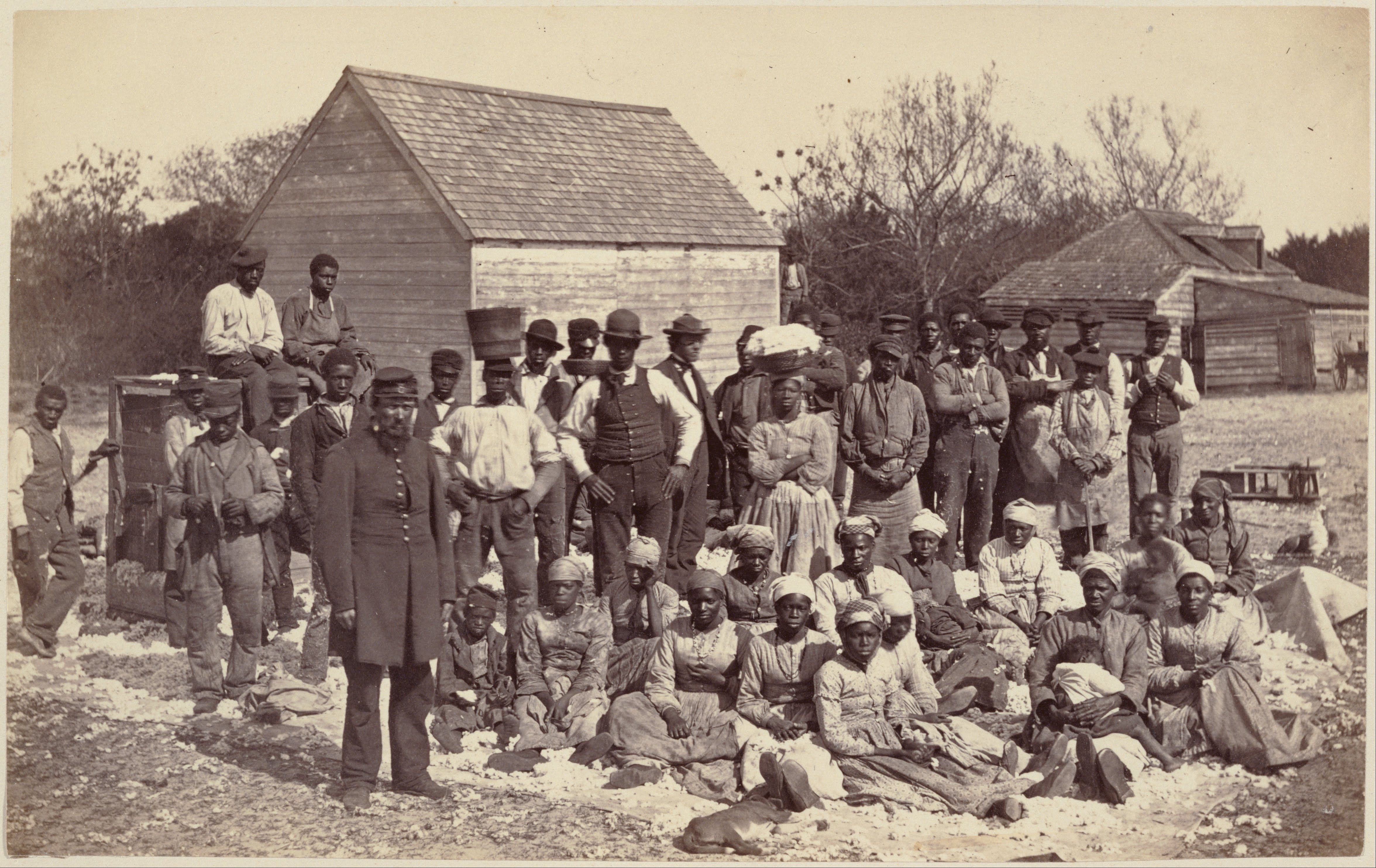

The proslavery southern plantation owners, on the other hand, dependent on slave labor saw to it that slavery was protected within the new Constitution. This political faction of southern slave owners was instrumental in securing to their advantage constitutional protections for slavery, such as delaying any ban on the slave trade, assuring the return of runaway slaves, and most important the Three-fifths Compromise which awarded southern slaveholding states undue seats in the House of Representatives and in electoral votes for president.

“The two-party system was not indicative of rigid ideological differences about the form of government but instead was about how best to construct the policies that would serve the interests of white political class domination.”

These concessions to the southern faction, though contentious, were deemed necessary to smooth over internal antagonisms and maintain white political class unity. And as the American two-party system emerged, the two dominant parties simply represented the two factions within the white American political class. However, the political class is not a political party; the political party is only a tool for controlling the state and hence the political system, and for attracting voters, sympathizers, and sycophants.

Starting with Thomas Jefferson, the Democratic Party (which formally took this name in 1829 during the campaign of Andrew Jackson) was essentially the party of the American ruling class but dominated by the proslavery southern faction and so assumed the political role of maintaining white political class solidarity and white consensus in general. The Whig Party formed as an opposition political party to Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party and represented a coalition of diverse interests and ushered in the modern two-party system. However, the two-party system was not indicative of rigid ideological differences about the form of government but instead was about how best to construct the policies that would serve the interests of white political class domination.

But as the issue of slavery became the centerpiece of national debate (just as it had during the Constitutional Convention of 1787), it split the two dominant parties internally and opened the door for the emergence and success of a third party, the Republican Party in 1854, composed primarily of antislavery northern Democrats and Whigs. This left a southern Democratic Party of slavery supporters and a Republican Party of largely northeasterners and burgeoning westerners opposed to the expansion of slavery.

The Republicans sought to keep slavery out of the new territories, not for any altruistic reasons, but as a means of protecting the white working-class from competing with slaves. Factional divisions within the Democratic and Whig parties allowed the Republicans to contest Democrats for political control of government and undermine the proslavery majority in Congress. And, when the Republican Party won the presidency and both houses of Congress in 1860 this led to southern secession and the Civil War—an intra-class war.

With the Civil War defeat of the proslavery southern political faction, the Reconstruction Era began—a temporary attempt at punishing but also transforming the south and integrating the newly freed slaves into American society. Led by the Radical Republicans in Congress—a bloc within the Republican Party opposed to slaveocracy and angry with the southern secessionists—constitutional amendments were ratified and civil rights acts passed as a means of incorporating African Americans into the social and political milieu of the south and the nation as a whole. The Republican Party, with the support of newly enfranchised African Americans, took political control of the southern states and guided the Reconstruction agenda of southern transformation.

“The southern Democratic Party’s goal through terrorism, racism, intolerance, and white chauvinism was to turn back every democratic and egalitarian trend and defend against the disintegration of the southern way of life.”

However, the contested presidential election of 1876 and the compromise that resolved it ended Reconstruction. The Democratic Party reestablished controlled of the south and the former slave-owning southern faction ruled once again.

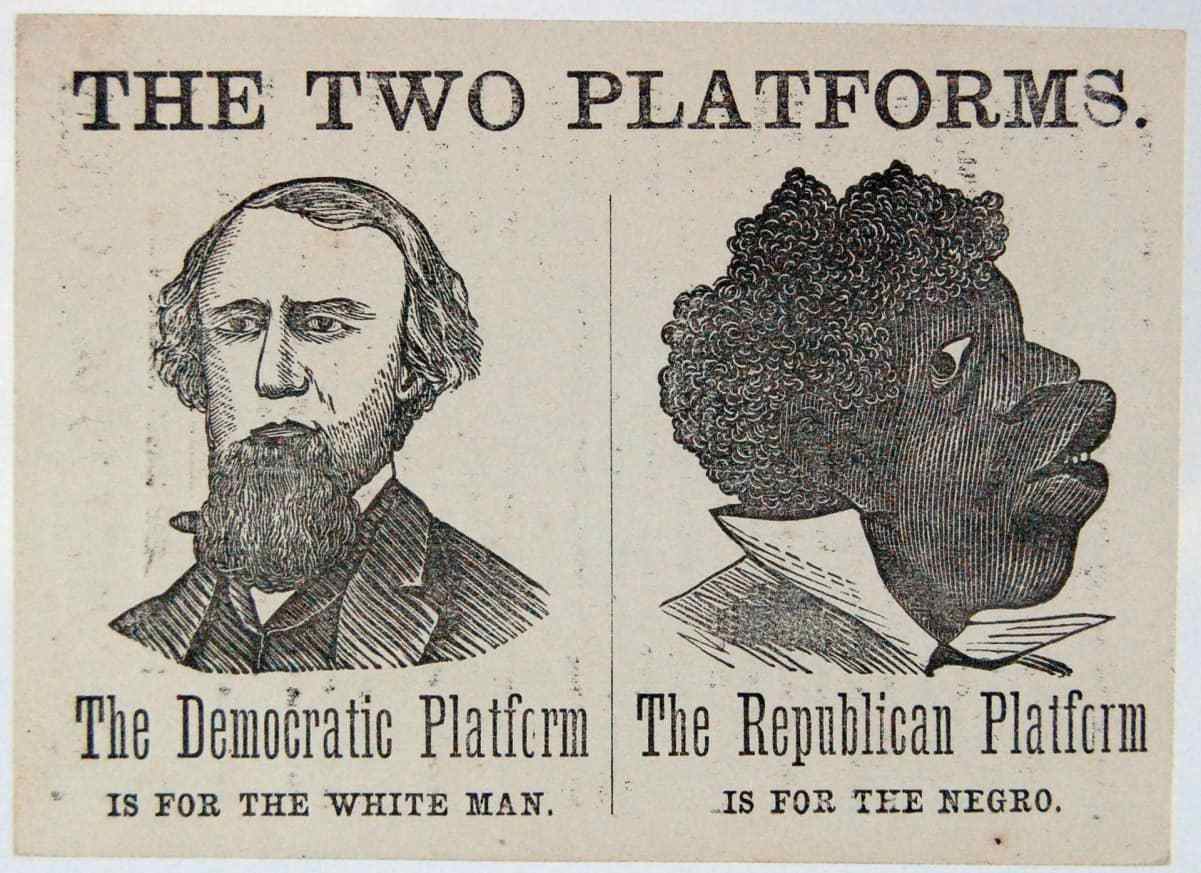

Therefore, a key issue in the formation of the Republican Party was slavery (also the key issue in the formation of the American republic). And because of the Republican Party’s antislavery position and African American support, the southern white ruling class, via the Democratic Party, was able to undermine the Republican Party, at least in the south, by making the Republicans a party of African Americans trying to establish “Black domination.” The Democrats represented the ruling interests of the old plantation south and the Republicans, because they represented antislavery sentiment and support for southern Reconstruction, were castigated as anti-white. Consequently, the Democrats labeled the Republican Party as the “Black” party, which meant that the Democrats were the true “white man’s party.” And so, from this point forward, the two major political parties made race a major part of the content of political discourse and electoral politics.

So, for the first time, during Reconstruction and after, the fascist tendency within American capitalism emerged in the south and inside the southern wing of the Democratic Party. Racist demagogues were now able to implement their fascistic terror against their enemies—Radical Republicans and their Black allies—and defend themselves against the disintegration of the backward southern capitalist system and its customs brought under threat by Reconstruction. They were able to wrest southern regional political power from the Republican Party and return many Blacks to as close a condition to slavery as possible.

All the classic characteristics of fascism were on display. Using terrorist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, Knights of the White Camellia, White League, and Red Shirts African Americans were subjected to economic pressure, intimidation, physical violence, and murder; election fraud was rampant; and many white Republicans capitulated in the face of white southern pressure and abandoned their commitment to civil rights. The southern Democratic Party’s goal through terrorism, racism, intolerance, and white chauvinism was to turn back every democratic and egalitarian trend and defend against the disintegration of the southern way of life.

With only one party of any significance in the south—the Democratic Party—white supremacy was once again entrenched, and the southern white ruling class set the tone for race relations throughout the nation. The last quarter of the 19th century began the institutionalization of racial segregation and the implementation of American apartheid—Jim Crow. Well into the 20th century, African Americans were legally recognized as second-class citizens. The ascendency of the southern white ruling class faction was secure for a while.

“By linking African American political activism with New Deal liberalism (a tactic used during Reconstruction against the Republicans), a realignment of southern Democrats and conservative Republicans slowly took shape.”

However, the Democratic Party as a national political power would reemerge because of the Great Depression, the New Deal, and the leadership of Franklin D. Roosevelt. However, the emergent national Democratic Party dominance was built on alliances of unlikely groups, (e.g., Catholics, Jews, unionists, farmers, urbanites, white ethnics, and Blacks), and supported liberal policies, civil rights, and the expansion of government power and responsibility. This meant that the white southern political elite’s role and power within this coalition was diminished and therefore sharpened divisions within the Democratic Party. The liberal wing of the Democratic Party, primarily composed of politicians from the northeast and Midwest, began to purge the party of its conservative southern bloc. Ultimately, this led to the Dixiecrat Revolt in 1948 and the beginning of the breakup of the New Deal Coalition and the shift of white southerners to the Republican Party.

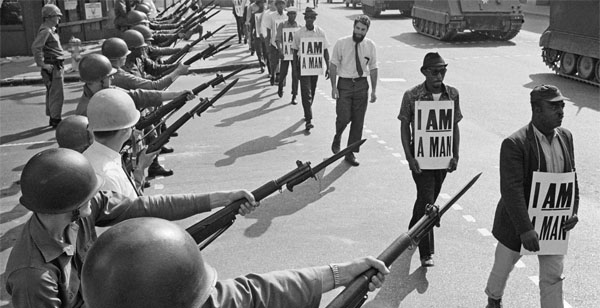

Of particular concern to southern Democrats was the emerging civil rights movement, and its support within the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, that began to reshape African American political identity and threaten southern customs, specifically segregation. This led to the Dixiecrat Revolt within the Democratic Party – formally known as the States’ Rights Democratic Party composed of southern segregationists intent on maintaining Jim Crow laws and white supremacy. Southern Democrats began a courtship with conservative Republicans that linked states’ rights, economic conservatism, and white supremacy.

By linking African American political activism with New Deal liberalism (a tactic used during Reconstruction against the Republicans), a realignment of southern Democrats and conservative Republicans slowly took shape. And, although the Dixiecrat Revolt was an electoral failure it opened the door for an alliance between southern Democrats and Republicans during the 1952 presidential election in which the Republican Party openly and successfully courted the southern white vote in support of Dwight Eisenhower.

The alliance would be strengthened during 1964 as the ultra conservative wing of the Republican Party took over leadership and nominated Barry Goldwater and began in earnest to wrest the Old Confederacy from the Democrats through racially inflected language and conservative policy positions. However, it would be Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan who would solidify the alliance and cement white southern support for the Republican Party through the successful implementation of Richard Nixon adviser Kevin Phillip’s “Southern Strategy” and Ronald Reagan aide Harvey “Lee” Atwater’s aggressive application of this strategy. However, this has not meant Republican Party dominance at the national level even though it has captured the white South. Since 1968, there has been more years of divided government, that is, the two parties splitting control of the presidency and Congress, than unified government, that is, one party controlling both branches of government.

“During the 1980s, white southern Democrats switched to the Republican Party in droves and once again made the south a one-party region, only this time for the Republicans.”

Also couched within this racial strategy was a neoliberal agenda to extend the free market, market deregulation, voter suppression, redistribution of social service provisions, and regressive tax policies that expand inequality and privatization, and shrinking the welfare state. The “Southern Strategy” took advantage of and instigated racial hostilities in order to restore historic class and race alliances between poor and working-class whites with economic elites who had become destabilized through the Great Depression and Keynesian economic policies as implemented by Roosevelt and the Democratic Party, and it played an important role in the reproduction of whiteness and racism and the restoration of historic class privilege surrendered through the New Deal and racial liberalism.

During the 1980s, white southern Democrats switched to the Republican Party in droves and once again made the south a one-party region, only this time for the Republicans. Ronald Reagan’s presidency proved to be pivotal in this shift. Reagan would mobilize white solidarity and finally break the New Deal coalition. Reagan became the face of the new Republican Party. What began in 1948 as a rebellion within the Democratic Party was now complete. The south was now a bastion of white Republicans.

The old southern faction completely transformed the Republican Party by shifting its support to that party. The two parties had now completely flipped in terms of political perspective and base of support. And the irony of it all is that a party once hated by white southern Democrats and that began its career as an antislavery party open to Black civil rights and Black political participation would become by the end of the 20th century the vehicle for reestablishing what was perceived as a loss of white socio-political space and a weakening of white privilege and hegemony.

“Therefore, the Office of the President, and specifically the Black man who occupied it, was disrespected because the white racialized space of the presidency had been transgressed”

So, when Barack Obama won the presidency, and was reelected, for many whites this was a crisis and an indication of white dislocation, a weakening of white supremacy. The unthinkable had occurred—the sanctity of the White House was desecrated by Blackness. The very symbol of whiteness, the apex of white domination, was invaded and occupied by Blackness. White supremacy was under assault. Therefore, white voters responded with Donald Trump, the anti-Obama. The idea that a phenotypically Black man, progeny of a Black African father, occupying the highest elected office in the United States, and therefore exercising his constitutional obligation as head of the government, head of state, and leader of the American Republic, challenged the white foundational understanding of American government and politics, that is, non-whites, especially descendants of African slaves, were not and are not really part of the constitutional compact.

Therefore, the Office of the President, and specifically the Black man who occupied it, was disrespected because the white racialized space of the presidency had been transgressed, and so there was a loss of reverence for the office. In fact, so disreputable had the Office of the President become, many whites preferred a white male who was not only unqualified, but vulgar, racist, misogynistic, incompetent, politically unsophisticated, and lacking a rudimentary understanding of American government and international affairs.

In their anxiety to escape what they perceived as a threat from the non-white other, the white masses were willing to sacrifice their economic interests, their national security, and endanger the nation to any white man who promised deliverance from the nonwhite threat and therefore put their faith in the most absurd, irrational, and racist arguments. The 2016 election of Donald Trump and what has transpired reflects this perception.

Consequently, the results of the 2016 election were not about appealing to what white people, in general, want; it was about who they are. Donald Trump did brazenly and conspicuously what the Republican Party has been surreptitiously doing for decades—appealing to white racial solidarity while pushing neoliberal programs. Trump and his fellow Republican compatriots and supporters espoused a form of white nationalism that was anti-internationalism, anti-democratic, politically autocratic, philosophically reactionary, anti-liberal, and demanding absolute loyalty. It was a nationalism that glorified the white national interests above all else. It was, in fact, a fascistic nationalism.

Donald Trump along with the Republican Party understood this. But Trump, more so than the Republican Party, spoke directly to what many whites saw as a betrayal of the “white nation.” He better understood the narratives and their generalizations, that is, stereotypes, caricatures, inferiorization, and derogation. He understood that by deploying these narratives he could better communicate with white anxiety toward the other. Trump understood this language of whiteness and was comfortable, unlike some other Republicans, within its lexicon. He boldly and shamelessly articulated the substance of this language, that is, racism and white supremacy.

The present moment in American politics reflects an ongoing factional struggle within the white ruling class establishment. When white supremacy is challenged or threatened, white Americans have always responded with a retaliatory backlash, i.e., a protest, and sometimes a panic, that reproduces racial inequality and protects white privilege and white supremacy. The extreme right-wing shift we see in the United States is not specifically a manifestation of the global political economy but rather the reemergence of an old political faction, which has once again ascended to political dominance.

Ronald A. Kuykendall is a Coordinator an Instructor at Trident Technical College, Charleston. He has recently contributed chapters to W.E.B. DuBois and the Africana Rhetoric of Dealienation, e.d, Monique L. Akassi; and Rhetorics of Whiteness: Postracial Haunting in Popular Culture, Social Meddia, and Education, eds. Tammie M. Kennedy, et al.

We are 100% reader funded. If you enjoyed reading this article and you got some benefit or insight from reading it buy a gift card or donate to keep Media Diversified’s website online

Or visit our bookstore on Shopify – you can donate there too!

I find it embarrassing that white Southerners, more than any other area in the country, practiced a one-party state in which they consistently voted for Dixiecrat legislatures and governorships for over a century after Reconstruction (and used ever possible tool to prevent African-Americans from voting in primaries or elections), while most other states outside of this region managed to vary between Democrats and Republicans. Now white Southerners vote solidly for Republicans with the exact sort of religious fervor as their ancestors voted for Dixiecrats, for mostly the same policies (except for slavery and Jim Crow).

Now in the South, the Democrats have become the “Black” party of diversity and economic justice, and white conservatives are largely united in the belief that economic justice is “socialism” and should never happen down here.

LikeLike

This essay says everything our history classes didn’t—thank you thank you thank you.

LikeLike