by Rowena Mondiwa Follow @RowenaMonde

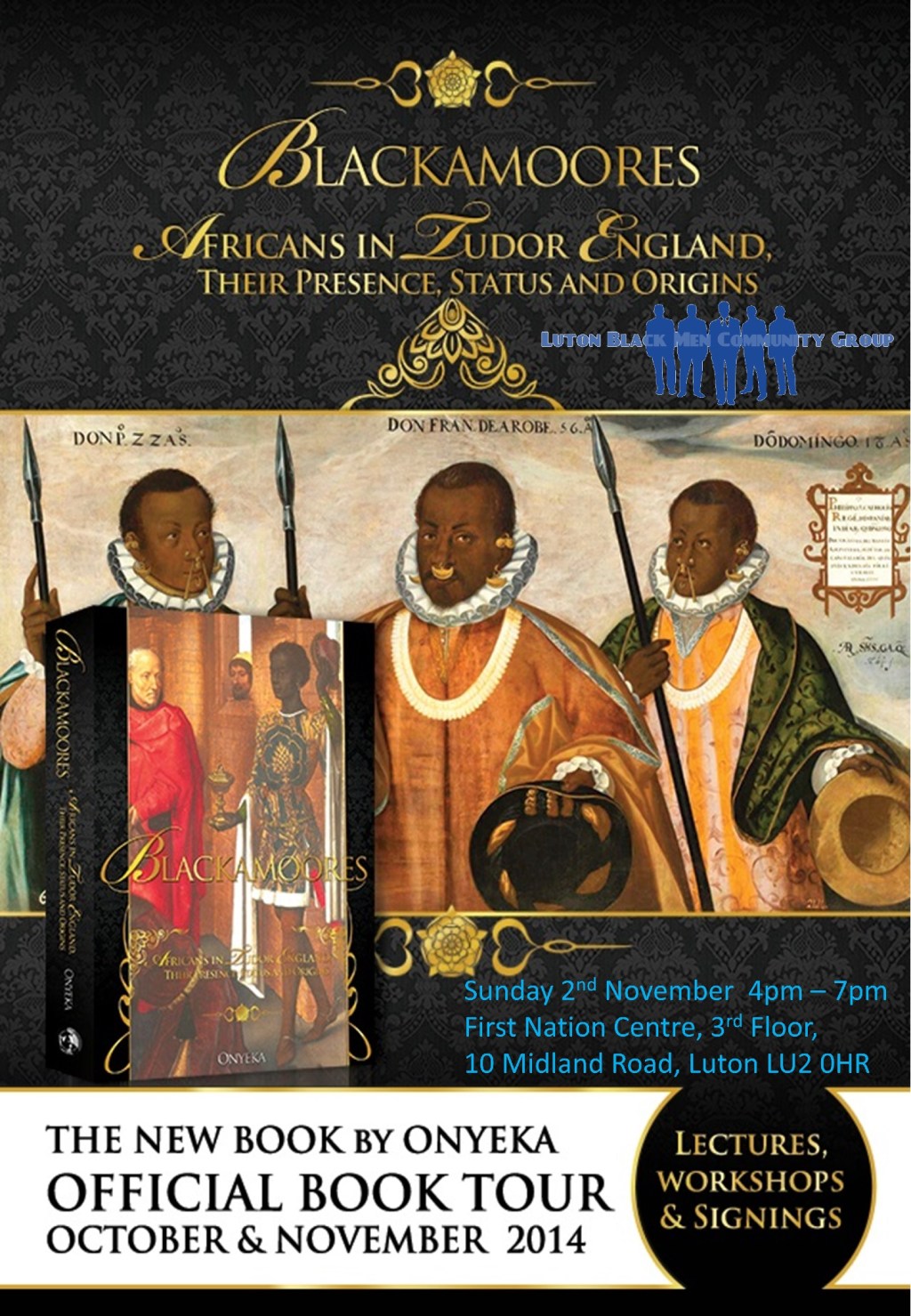

A criminally neglected part of British history is the true scope of the African diaspora in Britain that reaches as far back as Renaissance Europe. A new book by Onyeka Nubia seeks to rectify the problem, examining the lives of the thousands of blacks that lived in the UK in Tudor times. In Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, Onyeka Nubia shares research conducted in uncovering early evidence of Black existence in the United Kingdom, and proves that black presence was evident a lot earlier than is usually assumed. Nubia’s research focuses on the Tudor era (1485- 1603), specifically looking at the four English cities of London, Plymouth, Bristol and Barnstable.

This is not the first book published about African presence in England. Black Lives in the English Archives by Imtiaz Habib (2008) and Gustav Ungerer’s The Mediterranean Apprenticeship of British Slavery (2010) are two other books that look at similar subject matter and help substantiate the information uncovered in this research project. Additionally, just this year, academic Miranda Kaufman has published essays on the same research.

Using extensive data from letters and parish records, Nubia pieces together some of the unknowns, and paints a bigger picture of Black presence in Tudor England. These historical documents, one even signed by Queen Elizabeth I in 1596, clearly confirm the black presence in the country. Emma McFarnon in The Missing Tudors: black people in 16th-century England questions why history doesn’t acknowledge black Africans being part of that society. As she says, the numbers were quite large too, at least large enough for Queen Elizabeth I to have taken note in two letters signed by the monarch in 1596.

Who were the Africans? McFarnon says that from as early as 1558, parish records mentioned Africans using a diversity of terms such as “Blackamoores,” “blacks,” “moors,” “negroes,” “negars” and “Ethiopians” to describe people of African heritage. Africans were buried in England in the 16th Century, Africans such as Anthony John who died on March 18, 1587. Africans were also found in the royal court, men such as John Blanke, the black trumpeter who attended court from 1506-1512. Evidently, Africans where an important part of the social fabric.

Nubia courageously confronts the assumptions made by a few of the prominent authors of Black history in England that Africans were brought to England as slaves. Indeed, the author found firstly that the term slave when used was a “temporary or transitory” term; additionally, there is evidence of Africans marrying English people and having children.

‘A report in 1578 declared ‘I myself have seene an Ethiopian as black as cole…taking a faire English woman as wife [they] begat a sonne in all respects as blacke as the father.’ James Albert Gronniosaw (an African prince, enslaved at 15, who served in the British army and later wrote his memoirs) married an English weaver and settled in Colchester.‘nationalarchives.gov.uk

One of the examples of Africans found in important jobs at the time is a man named Fortunatus, who was in the employ of Robert Cecil, a member of Queen Elizabeth I’s Privy Council, proving that blacks in Tudor times were not always confined to the lower classes. Black representation in 16th and 17th Century art and literature was not unusual. Juriaen Van Streeck (1632-1687)’s painting “A Still Life with a Moorish Servant” depicts a Black man. Jan Brueghel, a prominent Flemish artist also has paintings of Black subjects.

With well-cited facts, records and other documents, credibility is lent to an under-researched and generally unpopular area. Onyeka Nubia acknowledges the challenges of working on such a neglected topic and stresses the history of the African diaspora be “taken more seriously.” Nubia carefully details the problems faced when researching the historical data of blacks — it begs the question, why are modern historians so uncomfortable with discussing the historical Black presence in Renaissance Europe? This is an area of history that hegemonic historians ignore.

It is timely that I read Nubia’s book during Black History Month here in North America. In television shows, films and books by popular historians, the presence of black Tudors is not acknowledged. As McFarnon says, the problem with not acknowledging them is

“it influences how we develop public policies on a range of important matters and it affects how we educate children in schools.” Historian Marika Sherwood goes further and states that black people often say “in this curriculum I don’t exist.”

Blackamoores shows us parish records, letters and artwork as primary sources, detailing how Black people have been a part of European society since at least the fifteenth century. It is obviously important for the African diaspora to know their roots and see evidence of themselves in history, a history that has often been whitewashed in popular culture and history books until recently. As Onyeka Nubia writes,

“this tension exists and to some extent is inevitable until Black history and in particular the study of Africans in the Diaspora is taken more seriously.”

It’s time for academia to take the African diaspora seriously.

Find more information at narrative-eye.org.uk and sign their Petition to Education Secretary, Michael Gove, to Reflect True English History by Including Black Tudors in the National Curriculum

All work published on Media DIversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not republish anything from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information go here.

_______________________________________________

Rowena Mondiwa was raised in the UK and Africa and currently lives in Vancouver, Canada. She is currently a first-year graduate student of International and Intercultural Communication. Rowena is interested in education, the arts, literature and cultural and diversity issues. She blogs at Les Reveries De Rowena and can be found on twitter @RowenaMonde

This piece was edited by Désirée Wariaro

Related articles

- The Missing Tudors: black people in 16th-century England (historyextra.com)

- Black Prsence: Asian and Black history in Britain 1500-1850 (nationalarchives.gov.uk)

- (Blacks In) Tudor Britain (mirandakaufmann.com)

- Mixed Marriages in the Eighteenth Century (nationalarchives.gov.uk)

- People of Colour in European Art History ( medievalpoc.tumblr.com)

Leave a comment