Yellowface at the Edinburgh Fringe

by Anh Chu

UPDATE: The Fringe and venue are open-access platforms which do not have jurisdiction over show content. The venue has sent staff to watch the play after our conversation. The play has added an address to the audience prior to the show to explain that it is intended to be a critique of racism.

Open-access. Artistic expression. Freedom of speech. Art, particularly live theatre, has the potential and power to affect change. I should know. I was so moved by a play that I watched that I gave up a lucrative corporate gig to focus on play writing.

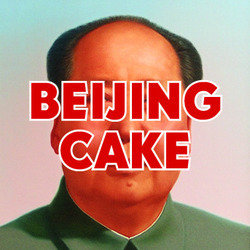

As a Canadian-Chinese writer who currently has a show at the 2013 Edinburgh Fringe Festival, imagine my excitement at seeing a selection – albeit a minority of the nearly 3,000 shows available – of East-Asian theatre available. So I, along with cast members Siu-See Hung and Julie Cheung-Inhin, excitedly went to see a play called Beijing Cake. With a name like that and Chairman Mao’s picture on its posters, we assumed it was going to be a Chinese play, probably with Chinese actors in it.

We never expected it to, God forbid, be from the point of view of an East Asian, but we did not expect in 2013 to experience blatantly offensive yellowface and racism.

We never expected it to, God forbid, be from the point of view of an East Asian, but we did not expect in 2013 to experience blatantly offensive yellowface and racism.

Firstly, we want to point out that this is not a review. Indeed, it cannot be: although we went to Beijing Cake to see what a play with such an intriguing name was about, and potentially (naively) to support East Asian artists, we were unable to finish watching the play. We stayed for 15 minutes of what felt like being slapped in the face while approximately 30 audience members laughed away.

The play starts off with two white actors and two black actors coming out in traditional Chinese costumes to perform a mock Chinese dance waddle that made our fists clench. The dialogue then began with the white American protagonist (Sarah Rosen) talking loudly and slowly to the black actress (Cassie Da Costa) playing Mei Hwa, asking how to say certain words in Chinese. Da Costa replied in a made-up “Chinese” language that was clearly meant to sound Chinese. (Indeed, it felt like “Chinky Chonky shu shu shu” mockery). Later on when talking to the playwright, Rachel Kauder Nalebuff, about the “Chinese” used in the play, she explained they wanted to make up the Chinese language rather than use real Chinese so as to not offend the Chinese people.

Image from Kickstarter

Image from Kickstarter

We hoped that the joke or irony would come out soon, but when the yellow-faced black actor (Gabriel Christian) started to portray an elderly Chinese man chucking money at a white woman to buy her unborn child, we could take no more. Perhaps the most insensitive and hurtful part of the play was the portrayal of the ghost of Mao Zedong as a kindly paternal figure that Rosen’s character repeatedly goes to for comfort and hugs. A parallel of this would be painting Hitler or Mugabe as a friendly confidante.

After walking out in total anger, we regrouped ourselves to talk to the people behind the project. First of all we approached the cast who told us to wait with a man until the writer was free to see us. This man did not tell us who he was until asked directly; he was in fact one of the producers of the show. We asked him why he did not cast East Asians in the East Asian roles, and he smiled and stated that he believed white actors should be able to play any colour role they liked as otherwise the industry would be very limiting. When we questioned this point again he deferred responsibility to the writer and said he didn’t want to talk to us unless we were lawyers.

When we eventually spoke to playwright Kauder Nalebuff, she was the perfect politician. She apologised about the fact that we found it offensive, but maintained that she had tested the play with many different audiences to make sure it did not offend and that she believes this was achieved. We then asked her how many of these audience members were of East Asian decent and she did not reply. We also asked her about her casting choices. She said that in her play (a play we hasten to add is called Beijing Cake and is set in Beijing) she did not want to pinpoint the Chinese, but that casting was to represent that people are different and she wanted people to ruminate on stereotypes. Since our chat, each show is now prefaced with a disclaimer, followed by a post-show Q&A in an attempt to justify, to me, these nonsensical choices.

As a courtesy, we spoke to the venue about our concerns, to let the manager know media had been notified and a Twitter storm was brewing. After being initially dismissed as something not worthy of his attention, he proceeded to state the pointlessness of our subjective opinion which was therefore not worthy of a proper dialogue. Our concerns were furthermore diminished as everyone else liked the show and we were the only ones who had made a fuss. No media will ever pick up this “story.” Basically we are wasting our time. It’s the Fringe. Worse things have been shown. Blacking up is now trendy in America. Anything goes. The English here just deal with [racism].

So what’s the big fuss, we’ve been asked? Don’t we believe in freedom of expression? Are we humorless, uptight, oversensitive as we have been made to believe? These questions, in my opinion, are intended to degrade our judgement, to silence. Indeed, there is no dictionary definition of yellowface – the absence of this alone signifies the invisibility of this issue. If blackface is no longer acceptable, why is yellowface? If this article was about blackface, there would likely be instant public outrage. Instead, this is seen as a non-issue. We are faced with intimidation from establishment. Patronisation – at all levels, across the board. The real question that should be begged here is: What is each of our responsibility and complicity in this discrimination, as audience members – and artists?

Racism is defined as the distinguishment of a race as superior or inferior. This is a definition but the impact is not an intellectual construct. Yes, it can be analysed as such, but for those who have experienced it, this offense is visceral – imbued and embedded with centuries of history and culture, which informs the receiver of it. Along with discrimination, it cannot be fully understood by a person who has never experienced it, nor from those of non-minority positions telling us how we should feel.

Unfortunately, it seems certain types of racism and discrimination are still deemed acceptable, nay, desired comedic devices by artists and audiences. Similarly, the exploitation and representation of East Asian cultures by those outside it, continues. We are incredibly grateful to pioneers like Daniel York for paving the way for discussion about equal treatment of East Asians in the arts. For sticking his neck out in light of the recent RSC Orphan of Zhao scandal

We, you and I alike, as fellow human beings, are part of the problem. Unless we speak up about these issues.

So. Here we are.

UPDATE Mon 9 Sept:

Related

#BeijingCake anonymous audience member review-Four reasons why “Beijing Cake” is offensive

For the uninitiated: Beijing Cake is a Northern American play which explores the racial stereotyping of Chinese people and the issues surrounding immigration and culture. In Beijing cake this is presented to us as a world where roles are reversed and American people desperately want to live in China. Produced by Year of the Horse, a virgin theatre company, the play casts African Americans as the Chinese, who dress in full 18th century Chinese dress, speak in “chinky-chonky” Chinese accents and talk gobbildy gook in lieu of any Chinese dialect. The play aims to lampoon such stereotypes, using its own absurdity to highlight the absurdity of racial stereotypes.

Many people in the East Asian community have taken offense at the play, and the responses to their outrage from the producers and others involved in the production has been apathetic and dismissive.

Anh Chu is a former TV editor/producer, journalist, food critic and communications specialist, turned actress and playwright. Her plays Something There That’s Missing, Bonk! (co-writer) are both playing at the 2013 Edinburgh Festival Fringe. She has written sustainability and lifestyle pieces for Canada’s The Globe & Mail, Avenue magazine, Metro, and more. Tweet her @AnhChuWriter

BRITISH EAST ASIAN ARTISTS

Work to raise the profile of BRITISH EAST ASIAN ARTISTS* nationally as well as in London. To promote Cultural Exchange. To challenge prejudice & stereotyping FACEBOOK

Related articles

- Where exactly are my British Chinese role models? (newstatesman.com)

Leave a reply to bringreaner Cancel reply