He was the first black player to participate in the Sugar Bowl, Bobby Grier said his memory had filtered out most of the negative aspects of his experience.

For Grier and other black athletes, the bowl game was a galvanizing event of the civil rights era.

In December 1955, Gov. Marvin Griffin of Georgia, a segregationist, demanded that Georgia Tech not play in the Sugar Bowl against Pittsburgh because the Panthers’ team included a black player, Grier.

“The South stands at Armageddon,” Griffin said in a telegram to Georgia’s Board of Regents, detailing his request that teams in the state’s university system not participate in events in which races were mixed on the field or in the stands.

“The battle is joined. We cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in this dark and lamentable hour of struggle.”

On Jan. 2, when West Virginia and Georgia play in the Sugar Bowl in Atlanta, there are no plans to commemorate Grier’s breaking the bowl’s color barrier. But there is no denying its significance.

A day before Griffin’s statement, Rosa Parks refused to yield her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Ala. Although Grier’s situation may not have been a similarly seminal moment in the civil rights movement, it received comparable national attention that month.

A black football player had never played in the Sugar Bowl, which is held annually in New Orleans. (The game was moved to Atlanta this season because of Hurricane Katrina.) Pittsburgh officials agreed to participate only if Grier, a fullback and linebacker, could play and if the sections of Pitt fans were not segregated.

Griffin, who died in 1982, was widely criticized by students and the news media leading up to the game. Georgia Tech students protested at the governor’s mansion in Atlanta and marched on the state capitol, burning Griffin in effigy. David Rice, a member of the Board of Regents, called Griffin’s comments “ridiculous and asinine” in an article in The New York Times. Georgia Tech’s president said that his team would not break the contract to compete in the Sugar Bowl.

“Stupid,” Grier said recently in an interview at his home when recalling Griffin’s comments. “Why did the governor need to jump into sports?”

Black players had participated in other bowl games, like the Cotton Bowl in Dallas, but Grier was credited as being the first black player to participate in a bowl game in the Deep South.

“It wasn’t the only national racial incident in college football, but it was the last big one,” said Michael Oriard, who detailed the controversy in his book “King Football.” “The national press was overwhelmingly against Griffin, and it made the South look pretty stupid. It was pretty clear at that point the direction that history was going.”

Georgia Tech had played against black players before, including a game at Notre Dame two years before, but never in the South.

“It was made into a situation when the governor acted like a horse’s backside,” said Don Ellis, a right end for Georgia Tech. “The governor didn’t reflect the attitude of the Georgia Tech football team at all.”

Griffin ran for governor on a platform of segregation “through hell or high water.” In his telegram to the Board of Regents, he went on to say: “One break in the dike and the relentless seas will push in and destroy us. We are in this fight 100 percent.”

His son, Sam Griffin Jr., who was a student at Georgia Tech at the time of the controversy, said his father was not a racist. He said that his father ran as a segregationist and his position was simply a political stance indicative of the political hyperbole of the time.

Sam Griffin Jr. said his father was opposed to Georgia Tech’s playing in the game as a matter of upholding segregation laws. If he had not, Griffin Jr. said, his father’s critics would have panned him.

Griffin Jr. added: “No one was going to get elected back then who didn’t run on that type of a platform. He was not a racist. I don’t know if you can understand that or not. A segregationist believes in segregation, equal but separate. It was the way things were. It had been that way for 100 years.”

The team stayed at Tulane for most of its trip because blacks were not allowed at many hotels. According to an article in The Atlanta Daily World, Grier made history in New Orleans as the first black to attend a social function at the Old St. Charles Hotel.

Grier could not attend some team events, but he found a warm welcome elsewhere. The fraternities at local colleges held parties in Grier’s honor. “They treated me like a celebrity,” he said.

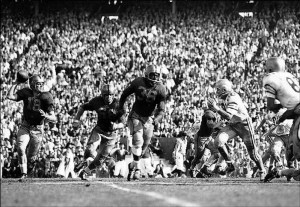

Grier played offense and defense in the game and had the game’s longest run – a 28-yarder. But the low point was a controversial penalty called against him in the first quarter that ultimately proved the difference in Georgia Tech’s 7-0 victory.

Grier, who is retired after a career as a foreman for US Steel and an executive at Allegheny County Community College, keeps a scrapbook from the game. The letters arrived from Texas, California, Alabama, Illinois and Tennessee, and from as far away as London. One New Orleans disc jockey wrote to Grier, “You are regarded just as much of a trailblazer as Jackie Robinson was in his debut in Brooklyn.”

Grier said he did not remember one negative letter, phone call or shout from the stands. He looks back at the 1956 Sugar Bowl as a turning point.

“I learned that things were going to change and things were a changin’,” he said, smiling. “It showed that sports has a way to change a whole lot of things.”

Leave a comment