Like so many of us, I was spellbound by the recent conversation between bell hooks and Melissa Harris Perry that showed beyond any doubt the lively power of an intersectional analysis that concerns itself with the entanglements of race, gender, class and sexuality in history and in everyday life. One point that caught my attention was when bell hooks responded to a question from the audience, picking up on and problematising the use of the term ‘hypermasculine’.

We should be careful about how we use the idea of hypermasculinity when talking about black men, hooks argued: it is patriarchy not masculinity that is the problem. This distinction recognises patriarchy as more than an economic system of male power and privilege and acknowledges the ways in which gendered relationships of power are also racialised, infusing identity, emotions and perspective. Talking of patriarchy as a disease Cornel West writes,

I grew up in traditional black patriarchal culture and there is no doubt that I’m going to take a great many unconscious, but present, patriarchal complicities to the grave because it so deeply ensconced in how I look at the world. Therefore, very much like alcoholism, drug addiction, or racism, patriarchy is a disease and we are in perennial recovery and relapse. So you have to get up every morning and struggle against it.The distinction between hypermasculinity and patriarchy is a subtle and complicated point. hooks seemed to be saying that if there is no critical thinking space from which to examine masculinity in terms outside of a patriarchy we restrict the room for acknowledging what she refers to as the ‘wounded’ psyche of the black male. How then do we begin to value and nurture black men?

“One of the things I’ve always felt so strongly and really expressed in We Real Cool hooks said, ‘is the depth of black male woundedness by patriarchial terrorisim and until those wounds get addressed in some way I don’t think we’re gonna get the respect, the recognition, the care…”

It is this notion of “patriarchal terrorism” that intrigues me the most. I see this as a terrorism that hijacks black masculinity, in its continually evolving forms, and turns it in on itself[i]. For me, hypermasculinity is both a cultural artefact and a commodity of patriarchy, with repercussions for us all. It is the commodification of black hypermasculinity as an apparatus of patriarchy that I want to consider more closely.

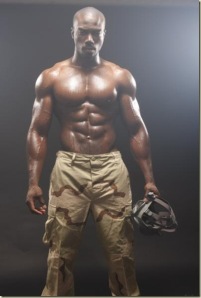

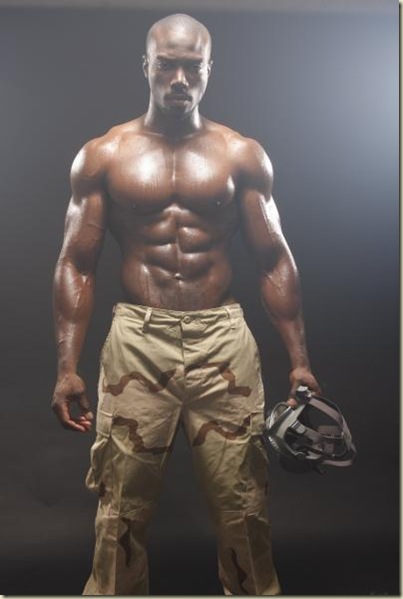

Through the exaggeration of dominant or ‘hegemonic’ masculinity, the image of black men as hypermasculine can become a cultural tool of self-regulation and self-loathing. This act of hijacking of what it means to be a man is a double whammy of subterfuge in modern culture where black masculinity has been co-opted as a purveyor of the market. In the Western neoliberal market cultural “blackness” sells. At the same time the blow of patriarchal domination is given a new sheen. It becomes a new false consciousness.

Through the exaggeration of dominant or ‘hegemonic’ masculinity, the image of black men as hypermasculine can become a cultural tool of self-regulation and self-loathing. This act of hijacking of what it means to be a man is a double whammy of subterfuge in modern culture where black masculinity has been co-opted as a purveyor of the market. In the Western neoliberal market cultural “blackness” sells. At the same time the blow of patriarchal domination is given a new sheen. It becomes a new false consciousness.

At the other end of the spectrum, we in our role as consumers of marketed blackness are also promised the privileges associated with cultural and social upward mobility and cool. Yet these promises are nothing more than mass consumerism built on a blackenised promise of an unattainable utopia. As we think of ourselves as self-determining as consumers (i.e. buying into the hype) we choose cultural commodities that signify “blackness” in the Kviftian sense of a commercial and exotic othering. We are duped into thinking that we have secured our individuality through the cultural aspirations of the market. Here is the second subterfuge; the market has become an institution in its own right.

In his book ‘Discipline and Punish’, the philosopher Michel Foucault describes how power is mediated through what he calls “discipline”. It is able to instil self-regulating behaviour in its subjects. However, whilst we are keeping our beady – yes beady, because, as Harris-Perry contends, we should be angry at the social injustices – eyes honed on structural inequalities are we becoming instutionalised by the market in much the same way as Foucault’s prisoner who rejects freedom in favour of the familiarity and ‘safety’ of captivity?

The power that this hidden-in-plain-view (market) institution wields is this very idea of commercial “blackness” that threatens to hold us ideologically captive too. It infiltrates our lines of resistance like the Trojan horse, as it is mediated through cultural images[ii] and market brandings of black hypermasculinity. Through these brandings such as the marketing of Hip Hop or here in the UK anything with the epithet “urban”, patriarchy is able to subjugate both men and women of all colours in one fell swoop. Think of Miley Cyrus and Lily Allen and how racialised patriarchy was played out on the bodies of twerking black women, even in Allen’s attempt to subvert it.

hooks recognises, as quoted earlier, that until we address the insidious nature of the role of patriarchy in the woundedness of black men, we will not be able to address the woundedness of black women (or anyone else). But why focus on the black male? Why is it important to address men as a priority?

I would argue that as patriarchy is racialised, we can discern its contemporary workings in the market objectification or fetishisation of the black male body. The market fetishisation of the black male physique [PDF] means that black men are necessarily kept on a perverse pedestal of hyper masculinity. There is little scope to explore other aspects of what makes a man a man – whatever that may be. Jackson[iii] talks about the iconography of the black male physique that is only allowed to be desired (by the white male gaze[iv]) through its visual depictions of woundedness, in the Hip Hop glorification of the gun-shot wound, for example.

I would argue that as patriarchy is racialised, we can discern its contemporary workings in the market objectification or fetishisation of the black male body. The market fetishisation of the black male physique [PDF] means that black men are necessarily kept on a perverse pedestal of hyper masculinity. There is little scope to explore other aspects of what makes a man a man – whatever that may be. Jackson[iii] talks about the iconography of the black male physique that is only allowed to be desired (by the white male gaze[iv]) through its visual depictions of woundedness, in the Hip Hop glorification of the gun-shot wound, for example.

This desire is ultimately forbidden so must be disguised or hidden. Here commercially exploitative iconography allows the “patriarch” to play out masculinity using a fantasy avatar of black hypermasculinity which subjugates all men and women. The legacy of this human objectification is that the black male body has indeed been marketed to designate the epitome of masculinity that is both feared and revered in equal measure. However, the market regularly co-opts what it once considered to be animal (just as slaves were also traded in markets). In so doing it still exerts and demonstrates its ownership of the commodity. We can see this in the fetishisation and market abstraction of the black male physique and the pornographic perception of his superior reproductive powers, both images of which are post-slavery, post-colonial dehumanising constructs.

The power of this version of black masculinity is such that westernised men (and women) are falling under the spell of black priapism and aspiring to this limiting commercial branding of masculinity that pivots on homophobia, misogyny and emotional infantilism. As black men, we run the risk of limiting ourselves socially and emotionally. For instance, a study of young people in the UK by psychologists Frosh, Phoenix and Pattman found that the valorisation of black boys as hypermasculine – physical, sporty and super-cool – also involved the rejection of the pursuit of intellectual activities as ‘gay’.

In other areas of social life such as family relationships, there is little room for the black man to be considered a “father” because in the archetype he is only expected to sire offspring using his superior reproductive powers. The black man is not expected to be a “husband”, rather as a stud or breeding machine he is expected to be sexually profligate. So resisting and not conforming to this deeply embedded social and archetypal narrative is to open oneself to marginalisation or worse still, abuse and violence. Even though more versions of black masculinity are now being forged as black men resist dominant stereotypes, difficult questions remain.

How can a black man truly respect women? How is the black man supposed to be a father when all that is required of him is to sire? How can a black man explore other sexual orientations, other masculinities or ways of transacting with other men) such as being gay/bi/trans, or at the very least being emotionally aware/sensitive/literate when all other men are sexual competition or threats?

We need to take a good look at ourselves in the mirror of cultural and ideological liberation. Our diasporic histories are indeed a strength, yielding many cultural innovations. We also need to come to grips with the darker legacies of our ancestral journeys in order to move on and to develop resilience. Of course, this will not be easy but we can make a start by acknowledging that we ourselves play a part in perpetuating the structural inequalities through our self-speak, through our transactions with each other and with women, and through buying into the market hype about ourselves.

I take inspiration from the Marxist sentiment of ideological liberation as articulated in the Garvey-inspired Redemption song[v],

Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery,” because “None but ourselves can free our minds”

If you enjoyed reading this article and you got some benefit or insight from reading it donate to keep Media Diversified’s website online

[i] I suppose I am alluding to a kind of Freudian “melancholic attachment” that the market (patriarchy or white male gaze see note vi) has to a form of masculinity that can never be/have or possess, as it is forbidden and can only manifest itself in grotesque caricature. In doing this the melancholia or loss (black hypermasculinity) becomes the only discursive lens through which to view masculinity per se.

[ii] So strong is this cultural embedding that it permeates our cultural associations of “blackness” far beyond the visual (e.g. music, language, sporting culture etc)

[iii] Jackson, C. (2011). Violence, Visual Culture, and the Black Male Body. New York, Oxford: Routledge.

[iv] Here, the idea of melancholic attachment comes into its own.

[v] Garvey, M. (1938, July). The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers. (R. A. Hill, & B. Bair, Eds.) Black Man magazine, 3(10), pp. 7-11.

Dr Ornette D Clennon is a Visiting Enterprise Fellow in the department of Contemporary Arts at Manchester Metropolitan University. He is also a composer and singer and has worked with a variety of bands, orchestras, artists and ensembles, including the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, The Halle, The Smith Quartet and Soul II Soul. His work explores the intersection between Arts, Culture and Social Agency. Ornette also works with communities, as a NCCPE (National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement) Public Engagement Ambassador and is interested in researching the applied outcomes of his cultural theory research in the communities with which he works as a music practitioner and composer. Find him on twitter @revkollektiv

This article was commissioned for our academic experimental space for long form writing curated and edited by Yasmin Gunaratnam. A space for provocative and engaging writing from any academic discipline.

Related articles

- Some thoughts on bell hooks – on angry women and postcolonial feminism (neocolonialthoughts.wordpress.com)

- Progressive Black Masculinity (lgbtblackmales.wordpress.com)

Leave a comment