by Karen Williams Follow @redrustin

The 17th century history of Indonesia and its anti-colonial figures brought Islam into the cultural life of South Africa, particularly for poor non-Muslims who lived together with Muslim communities. Growing up, I had a belief that Islam was the religion of freedom, without knowing why this was such a core belief of mine. Intrinsic to that experience is that Islam did not arrive in South Africa as a coloniser’s faith and its establishment and growth was rooted in the fight for freedom of enslaved people in South Africa. This contrasts directly with areas in Africa where Islam was a colonising, enslaving or hegemonic political and cultural force imposed from the outside. This would include for example, formerly enslaved Ethiopians (including children), and other Africans, who came to South Africa after being freed by the British from Arab slaving dhows.1

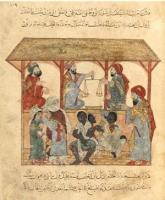

In Cape Town, Islam first established itself through the teachings of mainly exiled Indonesian scholars and royalty and was spread through the practices of the enslaved. In the poor, working class areas where the descendants of the enslaved continue to stay, there is an enduring belief that the city is protected by a number of kramats (shrines/burial places) of Muslim leaders who arrived as part of the exile and enslavement. The kramats form the “circle of Islam” that many believe protects the city. This is a guiding belief among the descendants of the slaves. There are particular legends that the kramats on the mountains are always unscathed whenever the city experiences its numerous summer mountain fires.

Two figures are key to the establishment of Islam in South Africa, namely, Sheikh Yusuf and Tuan Guru. Sheikh Yusuf was of royal lineage from Macassar and the place where he was exiled to in South Africa is popularly still known as Macassar. He was part of the anti-Dutch resistance and when he was exiled to South Africa, he became a key figure among slaves. The Dutch tried to house him far from Cape Town in order to reduce his influence among the slaves, but he was still a focal point for South Africa’s enslaved community. He often provided refuge for runaway slaves and the Dutch regularly accused him of encouraging the slaves’ bids for freedom. He is seen as the figure who established the first Muslim community at the Colony in the 1690s.

Imam ‘Abdullah ibn Kadi Abdus Salaam, known as Tuan Guru, was a prince from Tidore in Indonesia’s Trinate Islands who arrived as a prisoner in Cape Town in 1780. He served twelve years of his sentence and after being released he helped establish the first madrassa in 1793 and the first mosque in 1795.2

He authored one of the early Islamic texts during his incarceration:

While imprisoned on Robben Island, Imam ‘Abdullah [Tuan Guru], being a hafiz al-Qur‘an, wrote several copies of the holy Qur’dn (sic) from memory. He also authored Ma‘rifatul Islami wa‘ Imani, a work on Islamic jurisprudence, which also deals with ‘ilm al-kalam [Asharite principles of theology] which he completed in 1781. The manuscripts on Islamic jurisprudence, in the Malayu tongue and in Arabic, became the primary reference work of the Cape Muslims during the 19th century, and is at present in the possession of his descendants in Cape Town. His handwritten copy of the holy Qu‘ran has been preserved and is presently in the possession of one of his descendants, Sheikh Cassiem Abduraouf of Cape Town. Later, when printed copies of the holy Qu‘ran were imported, it was found that Tuan Guru‘s hand-written copy contained very few errors.3

In terms of language, Melayu and Bugis were used informally as (written and spoken) languages in South Africa in the 17th and 18th century.4 Islam would continue to be a driving force for intellectual production in South Africa: besides the Rajah of Tamboer’s Koran and letters written in Bugis, the first book ever published in Afrikaans in South Africa is believed to be a Muslim religious text, Bayan al-Din, written in Arabic script but read in the local slave dialect of Afrikaans, then known as Cape Dutch. It was published by the Kurdish religious leader, Abubaker Effendi, originally from Erbil in Iraq but who was a major religious figure in South Africa. The text was published in Constantinople (Istanbul). However, much earlier, madrassas provided education to slave children and prayers and incantations were captured in the emerging slave language of Cape Dutch/Afrikaans.

to be the first imam at the mosque. It was opened in 1794.

The royal Indonesian courts and advisors who were exiled to South Africa are not a historical curiosity. The implication of having highly literate scholars stationed at the Cape meant that early literacy and written intellectual production was driven not by the largely-unschooled white society and enslavers, but by the Asian (and at times Arab) captives. Some of the prisoners enslaved upon arrival in South Africa were also literate. The Indonesians brought not only Islam to South Africa, but madrassas which served as early schools. The study of Islam helped the development of the creole language that came about with the intermingling of South Africa’s indigenous African languages, with the Asian, African and European languages spoken at the Cape. Colloquially, the language was initially called Cape Dutch and historians have found texts used in the madrassas where early forms of the language were written down.5 In its early stages, the language developed in two main ways: through the close proximity of indigenous and enslaved South Africans who lived and partnered with each other; and through being spoken by the intersection of indigenous Khoi people, their mixed-race descendants and enslaved South Africans. Later on, in order to cement a claim to the country, Cape Dutch would be sanitised and co-opted as Afrikaans, even though today the majority of speakers continue to be the descendants of indigenous and formerly enslaved people.

References:

South African History Online: Doman. First accessed 21 August 2016.

Robert C-H Shell, Children of Bondage, Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg, 2012.

Kerry Ward, in Cape Town between East and West: Social Identities in a Dutch Colonial Town, ed. Nigel Worden, Jacana Media, Johannesburg, 2012.

Ross and Schrikker, in Cape Town between East and West: Social Identities in a Dutch Colonial Town.

Africana: The Encyclopaedia of the African and African-American Experience.

South Africa’s Stamouers: Van Tambora, Rajah. Accessed 21 August 2016.

RootsWeb: Rajah of Tamborah & Rustenburgh Estate, the governors’ residency. Accessed 21 August 2016.

Gabeba Baderoon, Regarding Muslims: from slavery to post-apartheid, Wits University Press, 2014.

Karel Schoeman, Seven Khoi Lives: Cape biographies of the seventeenth century, Protea Book House, Pretoria, 2009.

Hein Willemse, The Hidden Histories of Afrikaans.

Jean Gelman Taylor, The Social World of Batavia: Europeans and Eurasian in Colonial Indonesia, University of Wisconsin Press (2nd Ed), 2009.

1740 Batavia massacre (Wikipedia). Accessed 22 August 2016.

Kramat of Sayed Mahmud. Accessed 22 August 2016.

Kramats – Cape Mazaars. Accessed 22 August 2016.

Dutch East Indies (Wikipedia). Accessed 24 August 2016.

Java War (1741-43) (Wikipedia). Accessed 24 August 2016.

South African History Online: 1700-1799. Accessed 24 August 2016.

1The South African academic Neville Alexander found out late in life that his grandmother was formerly enslaved, and from Ethiopia.

2 Kramats – Cape Mazaars. Accessed 22 August 2016.

3 South African History Online: 1700-1799. Accessed 24 August 2016.

4Ward p.86

5Willemse

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Karen Williams works in media and human rights across Africa and Asia. She was part of the democratic gay rights movement that fought against apartheid in South Africa. She has worked in conflict areas and civil wars across the world and has written extensively on the position of women as victims and perpetrators in the west African and northern Ugandan civil wars.

Indian Ocean Slavery is a series of articles by Karen Williams on the slave trade across the Indian Ocean and its historical and current effects on global populations. Commissioned for our Academic Space, this series sheds light on a little-known but extremely significant period of international history.

is a series of articles by Karen Williams on the slave trade across the Indian Ocean and its historical and current effects on global populations. Commissioned for our Academic Space, this series sheds light on a little-known but extremely significant period of international history.

This article was commissioned for our academic experimental space for long form writing curated by Yasmin Gunaratnam. A space for provocative and engaging writing from any academic discipline.

If you enjoyed reading this article, help us continue to provide more! Media Diversified is 100% reader-funded – you can subscribe for as little as £5 per month here or support us via Patreon here

Leave a comment