CONTENT NOTE: This piece will discuss rape and sexual assault (Here is a list of support services for survivors – via Alison Phipps).

by Shane Thomas Follow @tokenbg

For those who don’t know, here’s what you need to know: Footballer Ched Evans was found not guilty of rape in a trial that ended last Friday. We’ve written about him before. He was initially convicted in 2011, before being released on licence in 2014. Evans protested his innocence, and the conviction was subsequently quashed on appeal with the case being retried, resulting in last week’s verdict.

After numerous failed attempts to return to football, Evans was signed by Chesterfield. While well within their rights, the club’s motivation for doing so was clear when you read the comments from manager, Danny Wilson (who previously managed Evans at Sheffield United): “I think the decision of the club was very brave, but it was calculated, too… If he gets anywhere near where he was at Sheffield United, he’ll be a massive asset… If I didn’t know Ched, I probably wouldn’t have made the decision, but I did know him. And I know what he’s capable of as a player. That’s why we brought him.”

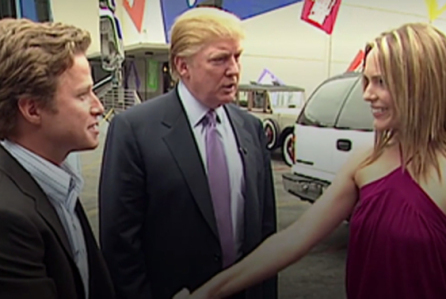

This all takes place during a time where a number of stories have converged to bring the issue of rape culture into sharp focus. The main one being Donald Trump acting unsurprisingly deplorable, as well as the Socialist Workers Party holding an anti-racism conference, despite being an anti-woman cesspool.

This all takes place during a time where a number of stories have converged to bring the issue of rape culture into sharp focus. The main one being Donald Trump acting unsurprisingly deplorable, as well as the Socialist Workers Party holding an anti-racism conference, despite being an anti-woman cesspool.

Football may be perceived as an escape from the real world, but it’s still very much a part of it. It influences, and is influenced by, what happens outside its bubble. A recent Evans goal was gleefully acclaimed by Chesterfield’s Twitter page. The replies below the tweet were a sewer of misogynist sentiment.

What Wilson and Chesterfield chief executive Chris Turner haven’t considered, or haven’t cared to consider, is that football’s place in British culture makes it a key breeding ground for educating men. There’s more to be gleaned from the sport than playing a high press or trying to find space in between the lines.

Similar concerns abound in the case concerning NBA player Derrick Rose, who is in the middle of a civil trial where he and two friends are accused of gang-raping a woman[1]. Like Evans, Rose has declared his innocence. And like Evans, the case hinges around the issue of consent.

It’s alarming that when initially questioned, Rose seemed unable to define what consent was. But equally alarming was when asked if his friends knew why they were heading to the home of the alleged survivor, Rose said, “We men. You can assume. Like we leaving to go over to someone’s house at 1:00, there’s nothing to talk about.” Evans, meanwhile, made this immodest observation in his trial: “Footballers are rich. They’ve got money. That’s what girls like.”

While not proof of guilt, these statements give a disconcerting snapshot of how Evans and Rose view men and women. To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with casual sex, whether it’s a little or a lot[2]. But ambiguity around consent provides men with an escape hatch from accountability. As Lauren Chief Elk-Young Bear and Shaadi Devereaux sapiently put it, “when we license men to treat consent as a matter for negotiation, predatory behavior becomes the norm.”

This ugliness is laid bare when we see that (according to Rape Crisis) roughly 85,000 women are raped every year, with a recent ONS report listing a 22% increase in police recordings. While men are also survivors, it’s women (and non-binary people read as women) who are left especially vulnerable[3].

In lieu of not fully comprehending consent, far too many men have decided that only they get to define it. I suspect Evans and Rose feel that – possibly beyond unfaithfulness – they have done nothing wrong. Had Evans not been charged (roughly 80% of instances go unreported), would the incident have been one of those, “You’ll never guess what I got up to last night, lads. Don’t tell the missus” stories?

Jessica Luther tackled this topic in her essential book, Unsportsmanlike Conduct, and writer Katelyn Burns explicated further: There’s more to team sports than just playing well. There’s a whole social structure, and for boys especially, that edifice is built on layers of masculinity.” She adds, “There was an unspoken hierarchy of respect based on who did what with which girl the weekend before.”

This piece isn’t a retrial of Ched Evans. The verdict is in. But what does require urgent scrutiny is the micro and macro influence men have, and how we often choose to inflame rape culture rather than act as a fire blanket. Much like the effects of Brexit on our immigration discourse, these cases serve to exacerbate an already troubling paradigm. Because unlike many other crimes, patriarchy has obtruded on the judiciary to make each case a referendum on the how the world mediates with women.

If someone is charged with burglary and found not guilty, we don’t cast doubt on future occurrences of burglary. Yet Evans’ accuser was forced to change her name and move home on five separate occasions due to doxxing and harassment, while the alleged victim in the Rose case has had her credibility called into question by dint of little more than photos of herself on her Instagram. She also isn’t permitted to remain anonymous throughout the trial.

I wonder if any male footballers felt uneasy about Evans restarting his career, or if any of the New York Knicks roster feel uncomfortable sharing a locker room with Rose? This is where the individual intersects with the systemic. Because there’s one area in which men seem to have little issue with consent. It’s in our massed consent to stay silent, affirming our male peers to prize their desires over women’s safety (Jeff Van Gundy being a rare exception). The sad irony is that men aren’t lacking a protective instinct. It’s what they’re trying to protect that’s so worrisome.

I wonder if any male footballers felt uneasy about Evans restarting his career, or if any of the New York Knicks roster feel uncomfortable sharing a locker room with Rose? This is where the individual intersects with the systemic. Because there’s one area in which men seem to have little issue with consent. It’s in our massed consent to stay silent, affirming our male peers to prize their desires over women’s safety (Jeff Van Gundy being a rare exception). The sad irony is that men aren’t lacking a protective instinct. It’s what they’re trying to protect that’s so worrisome.

Often the only noise to come from men is to parrot the canard that women are cunning and vindictive, wanting to destroy an innocent man to absorb his fame and money like a succubus. While there’s a history of false claims being made by white women against African American men that furthered white supremacy, who ever parlayed a fraudulent rape accusation into social betterment?

Teaching consent is hugely important, but its efficacy may be limited if men’s prime directive remains the consumption of women[4]. An enduring plank of succeeding at manhood is – in the words of Khadijah White – “the control and degradation of weaker others.”

The insulation of patriarchy is something men are clinging to like an infant with a comforter, and nothing is seen as worth giving that up; not even a structure that frames women as pleasurable commodities to be used and disposed of. This is the capitalism in the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy that bell hooks speaks of, where the mindset of collecting sexual encounters mirrors the mindset of acquiring material goods. A zero-sum game where men must not only win, but women must lose.

Retraumatising survivors and absolving assailants illustrates that: “In actual military conflict, war only has to be declared once. But the structural and individual effects of patriarchy work on an ouroboros loop, with a war on women being declared again and again.” Attacking a singular woman will also work to cast aspersions on the entire gender, while this dynamic is inverted for men, who can avoid any collective blame for the actions of an individual male because #NotAllMen.

And all to protect the citadel of patriarchy. It should be noted that misogyny isn’t even considered a hate crime throughout Britain. The Margaret Atwood line about women being afraid men will kill them is as relevant now as when it was first written. You may have noticed I’ve primarily referenced women in this piece. That’s because I’m saying nothing they – including those who identify differently on the gender spectrum – haven’t said first, and often.

Progress can only occur we listen to them, when we believe them, when we stop awarding each other man points for winning at patriarchy. When we stop – as Ijeoma Oluo magnificently put it – using women to authenticate ourselves as men.

Men have shown we don’t care about rape survivors. Despite the online celebrations, we don’t even care about Ched Evans. But we care that his acquittal means that we’ve ostensibly won. How many men will now feel ever more empowered in their shameful treatment of women?

Social privilege doesn’t only confer power. It confers power without consequence. And therein lies the problem. Men remain largely free to wield the unearned power of our gender, and it’s women who often suffer the consequences.

[1] – Lindsay Gibbs reporting of this case has been outstanding.

[2] – But only if you’re a man, it seems. Promiscuity is a common tool used to discredit women in these cases.

[3] – A lack of resources leave women of colour especially vulnerable.

[4] – Also, does this arrogation of women’s bodies contribute to the scarcity of out gay male players in sport?

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

“Two Weeks Notice” is Shane Thomas’s bi-monthly column encompassing “Pop culture to sport, and back again“ Shortlisted for EI Arts, Culture and Entertainment commentator of the year 2015

Shane can be found on Twitter, both at @TGEISH and @tokenbg (and yes, the handle does mean what you think it means).

Leave a reply to OirishM Cancel reply