Every few months, a high-profile case of violence against women and girls hits the headlines. But with it, a familiar debate resurfaces. Should we name the ethnic or religious background of perpetrators? Is transparency about identity necessary for accountability, or does it risk deepening racial divisions?

Some argue that we need to “name the problem” in order to tackle it. Secular feminists and campaigners, particularly those focused on issues like forced marriage or honour-based violence, often say that failing to discuss culture or community dynamics silences victims and prevents change. Their point is that without honest data, which includes ethnicity, we cannot see patterns or design effective interventions. But there’s another side to this argument, and one that feels increasingly urgent in today’s climate.

Because naming isn’t neutral.

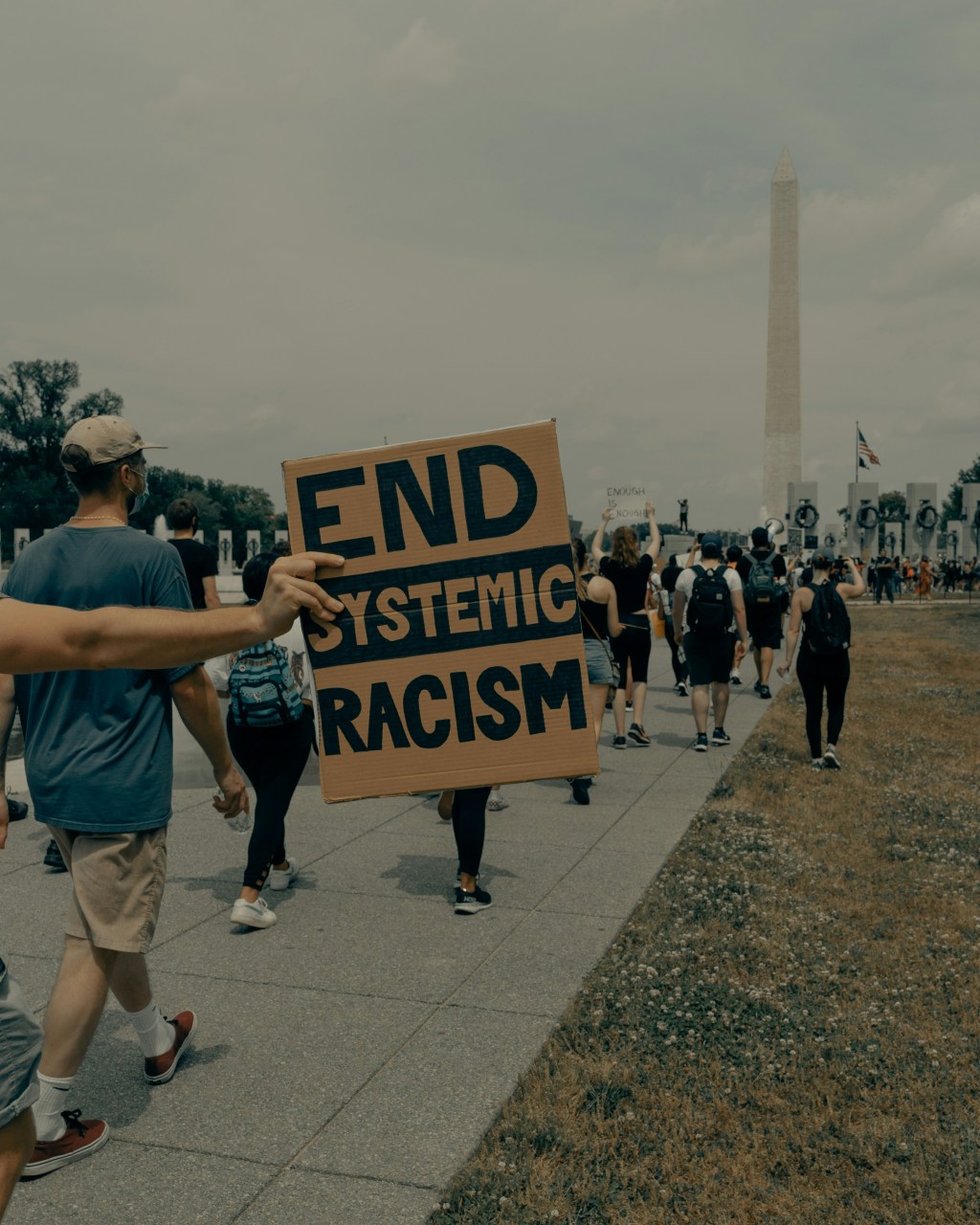

When the media reports that a perpetrator is “Asian” or “Pakistani” or “Muslim”, or “Somali”, it often collapses complex ethnic and cultural categories into a single, racialised label. “Asian grooming gangs,” “Muslim rapists” – these phrases don’t just describe; they stigmatise entire communities. And in a political moment where far-right groups are gaining traction by stoking fears about migrants and Muslims, as well as weaponising VAWG for their own racist agendas, such information becomes ammunition, not insight.

There’s also the question of double standards. When perpetrators are white, their ethnicity is rarely mentioned in the media. The violence is individualised; a man’s crime, not a community’s shame. But when the perpetrator is racialised, their identity becomes the story. This selective focus doesn’t help victims. It feeds anti-Muslim hatred and racism in general, reinforces stereotypes, and distracts from the fact that VAWG is a universal issue rooted in misogyny, not ethnicity.

Of course, data matters. We can’t design effective policy in the dark. But data should be used with care, and with an understanding of how it lands in a society where racism is rife and growing. Naming ethnicity in a headline isn’t the same as analysing data responsibly in a policy report. One informs; the other inflames.

So where does that leave us? Perhaps the answer lies in who is leading these conversations. Black and minoritised women’s organisations have been grappling with these tensions for decades. They’ve navigated how to name harmful practices without fuelling racist backlash, and how to centre survivors’ voices in the process.

As the debate continues, we needto ask: who benefits from the narratives we amplify? And who gets harmed?

Let’s make space for more honest, nuanced, and community-led discussions – before the far-right writes the story for us.

Kiran is the Head of Policy & Research at the Women’s Resource Centre

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

Leave a comment