by Zoé Samudzi Follow @BabyWasu

After her October interview with Tavis Smiley, I no longer think of Annie Lennox solely as the edgy, cool, and philanthropic Eurythmics frontwoman. I now see her as an embodiment of white ignorance. On her new album Nostalgia, Lennox covers “Strange Fruit,” a song popularised by Billie Holiday in 1939 that describes, vividly and hauntingly, a scene after the lynching of a black man. Lennox manages to describe her interpretation of the song without any mention of the lynching:

“Strange Fruit’ is a protest song and it was written before the Civil Rights movement actually got on its feet, got established. And because of what I’ve seen around the world, I know that this theme, this subject of violence and bigotry, hatred, violent acts of mankind against ourselves. This is a theme. It’s a human theme that has gone on for time immemorial. It’s expressed in all kinds of different ways, whether it be racism, whether it be domestic violence, whether it be warfare, or a terrorist act, or simply one person attacking another person in a separate incident. This is something that we as human beings have to deal with, it’s just going on 24/7. And as an observer of this violence, even as a child, I thought, why is this happening? So I’ve always had that sense of empathy and kind of outrage that we behave in this way. So a song like this, if I were to do a version of ‘Strange Fruit,’ I’d give the song honor and respect and I try to bring it back out into the world again and get an opportunity to talk about the subjects behind the songs as well.”

The Guardian hailed Lennox’s remake as a “brave reinterpretation.” This, of course, is in reference to her stylistic rendition of Billie Holiday’s blues vocals. The writer ignores Lennox’s very literal reinterpretation and whitewashed redefinition of the song. Lennox’s “Strange Fruit” stands in stark contrast to Holiday’s own understanding and description of her physical reaction each time she sang the song. As the story goes, the imagery was so sickening to her that she would vomit after every performance.

In her autobiography The Heart of a Woman, Maya Angelou recalls a discussion her son Guy had with Billie Holiday in 1957 about this very song:

On the night before [Holiday] was leaving New York, she told Guy she was going to sing “Strange Fruit” as her last song. We sat at the dining room table while Guy stood in the doorway.

Billie talked and sang in a hoarse, dry tone the well-known protest song. Her rasping voice and phrasing literally enchanted me. I saw the black bodies hanging from Southern trees. I saw the lynch victims’ blood glide from the leaves down the trunks and onto the roots.

Guy interrupted, “How can there be blood at the root?” I made a hard face and warned him, “Shut up, Guy, just listen.” Billie had continued under the interruption, her voice vibrating over harsh edges.

She painted a picture of a lovely land, pastoral and bucolic, then added eyes bulged and mouths twisted, onto the Southern landscape.

Guy broke into her song. “What’s a pastoral scene, Miss Holiday?” Billie looked up slowly and studied Guy for a second. Her face became cruel, and when she spoke her voice was scornful. “It means when the crackers are killing the niggers. It means when they take a little nigger like you and snatch off his nuts and shove them down his goddamn throat. That’s what it means.”

The thrust of rage repelled Guy and stunned me.

Billie continued, “That’s what they do. That’s a goddamn pastoral scene.” (Angelou, 1981, pp. 15-16)

Lennox’s artistic “reinterpretation” and subsequent narrative erasure is an illustration of white ignorance. White ignorance emerges from racialised epistemologies of ignorance. Epistemologies of ignorance pertain to not only knowing and not-knowing (epistemology is the branch of philosophy theorising about knowledge and its scope and nature), but also the “active reconstruction of one’s knowing” in a manner that may deliberately alter, obscure, or altogether erase the narratives of another (McHugh, nd). The epistemologies of wilful ignorance play a central role in whiteness’ epistemology of denial, that is the deliberate recreation of histories, events, sufferings and narratives of an other – in this case black people. These knowledges constitute a systematic social construction, “a political consequence of conflicting interest and structural apathies” (Proctor, 1995). It is in this context that whitewashing and cultural appropriation operate: it is a combination of white entitlement to cultural products, dominant narratives, and (re)definition of existence that these products become redefined at the expense of the cultural traditions from which they originate.

Lennox’s artistic “reinterpretation” and subsequent narrative erasure is an illustration of white ignorance. White ignorance emerges from racialised epistemologies of ignorance. Epistemologies of ignorance pertain to not only knowing and not-knowing (epistemology is the branch of philosophy theorising about knowledge and its scope and nature), but also the “active reconstruction of one’s knowing” in a manner that may deliberately alter, obscure, or altogether erase the narratives of another (McHugh, nd). The epistemologies of wilful ignorance play a central role in whiteness’ epistemology of denial, that is the deliberate recreation of histories, events, sufferings and narratives of an other – in this case black people. These knowledges constitute a systematic social construction, “a political consequence of conflicting interest and structural apathies” (Proctor, 1995). It is in this context that whitewashing and cultural appropriation operate: it is a combination of white entitlement to cultural products, dominant narratives, and (re)definition of existence that these products become redefined at the expense of the cultural traditions from which they originate.

In examining these epistemologies of ignorance as a product of the structures and ideologies of whiteness, we see the constructions or erasure of narratives in order to reproduce dominant racialised worldviews. Ignorance and dominance are inextricably linked in the context of whiteness because the forced perpetuation of particular worldviews can be construed as the “refusal of multiple ways of knowing,” (May, 2006). Charles Mills discusses the concept of white ignorance by stating that it emerges from white supremacy and the tacit agreement of those invested in whiteness to fundamentally misrepresent the world and to subordinate all other narratives pertaining to knowing and understanding (2008).

In this light, Annie Lennox’s statements, though reprehensible, make sense. Her feminism and conceptualisation of the world are both created from and centred on the preservation of these epistemologies of whiteness and the necessary ignorance and denial therein. Lennox had previously criticised the sexualisation of women in the music industry “from a perspective of a woman that’s had children.” She went on to comment about Beyoncé in the context of her own understandings of feminism:

“I was being asked about Beyoncé in the context of feminism, and I was thinking at the time about very impactful feminists that have dedicated their lives to the movement of liberating women and supporting women at the grass roots, and I was saying, ‘well that’s one end of the spectrum, and then you have the other end of the spectrum…Listen, twerking is not feminism. That’s what I’m referring to. It’s not—it’s not liberating, it’s not empowering. It’s a sexual thing that you’re doing on a stage; it doesn’t empower you. That’s my feeling about it.”

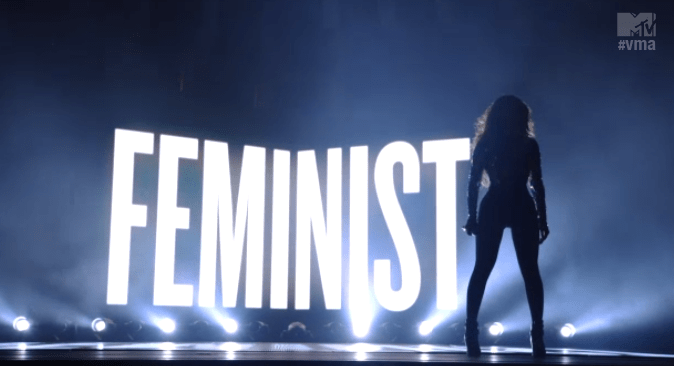

The reduction of Beyoncé’s dancing, sexual expression, and identification with feminism to mere “twerking” seems to come from a highly prescriptive and limited understanding of what feminism is. Lennox’s feminism is one where other cultural histories, aesthetics and performances are denigrated. Even in appropriating black female sexuality and using black women’s bodies as literal performance props, Miley Cyrus has largely escaped the feminist condemnation squarely aimed at black women. Mainstream white feminism’s entrenchment in white ignorance can render white women unable and/or unwilling to create space in feminism for nuanced and alternative understandings of women’s sexual agency and racialised experiences, and it led Annie Lennox to overlook the history of racialised violence and oppression that inflects Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” Even the line “black bodies swinging in the southern breeze” didn’t jar Lennox out of her wilful and racialised ignorance. Lennox’s refusal to recognise the historical context and significance of the song and to meaningfully engage with black history illustrates some of the tensions that continue to shape many of the interactions between intersectional feminism/womanism and white-centred mainstream feminism. The imbrication of whiteness in feminist movements perpetuates the notion that feminism is an exclusive playground, the entrance to which is protected fervently by white western middle-class cisgender heterosexual and able-bodied gatekeepers.

It is crucial to understand that this ignorance is not innocuous. It has far-reaching implications for what we collectively understand and hold to be true. Lennox’s treatment of “Strange Fruit” was not simply an unknowing misrepresentation of a song: it is a part of wider structures of social amnesia that systematically erase resistant narratives and counter-discourses, an Orwellian forgetting of something we once knew to be true (Wylie, 2008). This form of erasure has been called epistemic violence because the systematic suppression of narratives of oppressed people is an injustice that exists as a form of violence in itself. Not only is this erasure a form of epistemic violence, but the silence on the matters of race, sexuality, and gender-based violence serves as a mode of complicity with the dominant and oppressive status quo. My intention in drawing attention to Annie Lennox’s treatment of “Strange Fruit” is to show one way in which white feminism can be complicit with epistemic violence and injustices.

What is especially challenging about these forms of epistemic ignorance is that they cannot be informed and ‘corrected’ by fact alone. Stories of racism, news clippings of trans female murders, discussions of demographic-specific vulnerabilities, and constant critique by those who are the subjects of structural inequalities would be more than sufficient to establish ‘truth’. It is only through a conscientious process of acknowledgement and engagement that meaningful change can come about: an important albeit difficult conscientious process not wholly unlike the one that occurred at the Women in Africa and in the African Diaspora conference in Nigeria in July 1992. But what does this engagement look like? What are the particular processes through which we can mitigate these often overlapping epistemologies of ignorance? Admittedly, these are complex manifestations of deeply entrenched hegemonic histories and ideologies. I certainly don’t have all the answers, but perhaps if we can begin to describe the workings and varied effects of these oppressive phenomena, we can begin to bring them out of the shadows, name them, and work together to devise strategies for building and sustaining counter-narratives, discourses, and new epistemic traditions.

References

McHugh, N. (nd). Telling her own truth: June Jordan, standard english and the epistemology of ignorance.

Proctor, R.N., 1995. Cancer wars. New York: Basic Books.

May, V.M., “Trauma in paradise: wilful and strategic ignorance in Cereus Blooms at Night. Hypatia, 21(3), 107-135.

Mills, C.W., 2008. White ignorance. In: R.N. Proctor and L. Schiebinger, eds. Agnotology: the making and unmaking of ignorance. Stanford University Press, 230-249.

Wylie, A., 2008. Mapping ignorance in archaeology: the advantages of historical hindsight. In: R.N. Proctor and L. Schiebinger, eds. Agnotology: the making and unmaking of ignorance. Stanford University Press, 183-205.

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Zoé Samudzi, a first-generation American of Zimbabwean origin, has recently finished a masters degree in community development at the London School of Economics. She is dedicated to taking a critical and intersectional approach to all topics of interest, particularly in gender politics and public health discourse. You can catch her tweeting at @BabyWasu

This article was commissioned for our academic experimental space for long form writing curated and edited by Yasmin Gunaratnam. A space for provocative and engaging writing from any academic discipline.

Leave a reply to Bart Cancel reply