By Phenderson Djeli Clark Follow @pdjeliclark

This is Part 2 of a three-part series. Part 1 is here.

In modern fantasy, with its fascination with medieval Europe, it seemed almost fated that acts of “othering” would take root. Some of Western Europe’s founding notions of non-Westerners trace back long before colonialism, as early as the medieval era, where xenophobic fears (rational and irrational) of Muslim, Tartar or Mongol enemies were part of popular, religious, state and academic culture. We know this in part from the literature of the time, where non-Europeans (and non-Christians) are depicted as less than human and prone to wickedness.

(Courtesy of Grandes Chroniques de France, Bibliothèque Nationale)

The 12th-century Frankish epic The Song of Roland describes the Saracen king Marsile as “cankered with guile and every felony” and who “loves murder and treachery.” As a Muslim he is accused as one who “fears not God, the Son of Saint Mary” and is described as “black…as molten pitch that seethes.” The epic goes on to describe Marsile’s army: “Ethiope, a cursed land indeed; the blackamoors from there are in his keep, Broad in the nose they are and flat in ear, Fifty thousand and more in his company… When Roland sees those misbegotten men, Who are more black than ink is on the pen, With no part white, only their teeth….”

Similarly, in the 12th century Sowdone of Babylone the Christian Duke Savaris is slain in battle by Astrogot, a black giant of Ethiopia, a “king of great strength” who was “the devil’s son of Bezelbubb’s line.” In his command is another giant named Alagolafore, born of Ethiopia with skin both “black and hard.”

Ideas of exotic and dangerous “others” that lay poised to destroy Western Christendom continued beyond the era of the Crusades. And after 1453, with the fall of Constantinople to Muslim Ottomans, notions of the “dread Turk” haunted the minds of Europeans for generations, as their Eastern enemies rolled through the Balkans and reached the outskirts of Vienna. These fears of “enemies at the gates” would finally subside with the end of the Habsburg-Ottoman rivalry in the 18th century, coinciding in the political and economic ascendency of Western Europe.

Tolkien’s Southrons and Easterlings bear some interesting similarities with such medieval xenophobia. Tolkien was, after all, a medievalist. And his fans often point out that the uncomfortable racialisms in his literature mirror the perceptions of the Europeans he studied. At least that’s the excuse. But Tolkien didn’t live in medieval Castile or 17th-century Vienna. He lived in the 20th century. By this time the non-Western world had become the domain of European colonialism, now recast as a region to be studied, analyzed and categorized: the home to crumbling tyrannical empires with outmoded ideas and exotic (though inferior) cultures. It doesn’t seem hard to imagine that Tolkien was as influenced by such popular colonial notions of race and Empire as he was by WWI and industrialization. What we then see in his works are a melding of the old “threatening” East, mingled with many of the modern “othering” elements of exoticism and inferiority. It is a fetish that has become emulated in other works of modern popular fantasy, to varying degrees.

At one extreme, we have works like Frank Miller’s 300, which purports to tell the tale of the ancient Greek conflict with the Persian King Xerxes, recast as a didactic Orientalist fantasy. In Miller’s graphic novel, the Persians are made over as near monsters and tyrants–the opposite of the noble, freedom-loving and hyper-masculine Spartans. The moral of the story is clear: had the “democratic” Spartans fallen to the enslaving Persians, what we know as the modern “free” Western world may not exist. Never mind that the Spartans of history were hardly models of liberty; or that the Achaemenid kings of Persia were less than tyrannical monsters. What was necessary was to cast the Greeks in the role of the West, and the Persians as nightmarish “others.”

As if to emphasize these differences, Miller goes as far as to make many of the Persians “black.” The Persian king Xerxes in the comic is depicted as an ominous black giant, decked out in piercings and bling. The film adaptation only carries forward this extreme racialization in part; some of the Persians remain black; most are merely swarthy; nearly all are monstrous, with iron veils and other exotic forms of dress. The Immortals are outfitted in frightening looking Japanese mengu masks, under which their faces are disfigured. Xerxes, however, is reduced to a towering bronze non-distinct “other,” his fluid gender identity also marking him as deviant.

As if to emphasize these differences, Miller goes as far as to make many of the Persians “black.” The Persian king Xerxes in the comic is depicted as an ominous black giant, decked out in piercings and bling. The film adaptation only carries forward this extreme racialization in part; some of the Persians remain black; most are merely swarthy; nearly all are monstrous, with iron veils and other exotic forms of dress. The Immortals are outfitted in frightening looking Japanese mengu masks, under which their faces are disfigured. Xerxes, however, is reduced to a towering bronze non-distinct “other,” his fluid gender identity also marking him as deviant.

Long before Miller’s 300, the Battle of Thermopylae, on which the graphic novel and film are based, was translated from the fantastic into the real world, becoming a metaphorical rallying cry for European colonizers as they fought against hordes of swarthy “others” in the varied lands they conquered. This theme of the “few” brave white men (symbolizing Western civilization and progress) standing against backwardness and primitivism, served as the basis for Victorian writings on historical events such as the Anglo-Zulu War. And it became a staple of white heroic romanticism in later films, from John Wayne in Fort Apache (1948) to Michael Caine in Zulu (1964).

But as I said before, this matter is complicated.

Taking a more nuanced approach, there is Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time. In this expansive series we have the Aiel, who by description appear white (with blonde or red hair) but whose culture pulls on everything from Native American to Zulu to Bedouin customs. As desert people they are exotic and nobly savage to a fault, even following codes of honor that appear to have origins in the Japanese Samurai. Most of the cultures in the book of what passes for the “West” appear built on Eurocentric norms, even though adopting (or appropriating) varied aspects of non-European culture, making for an interesting mix. Picture white women in medieval European dress adorning their foreheads with the Bindi. The most swarthy Westerners, the coppery-skinned Domani, are also the most sexualized–with their women making seduction an art form and prone to wearing see-through clothing. Much the same can be said for the dark-skinned Sea Folk, whose work as traders is only equaled by the “graceful” nature of their women, their normalized semi-nudity, and the brutality with which they treat subordinates.

The most pronounced exotic “others” in the series appear in the form of the Seanchan–a mysterious empire from across the sea. Though multiracial in composition, their culture is unmistakably Eastern, bearing clear hints of Japanese, Chinese and Ottoman influences. Of particular interest, they are even ruled by a “black” Empress. True to their Orientalist nature, the Seanchan are conquerors; engage in slavery; have bizarre customs; are controlled by tyrannical rulers; and practice harsh codes of honor and status that overemphasize their exotic “difference.”

Unlike Tolkien and Miller, however, none of these “others” are really the bad guys in the larger plot of Jordan’s work; even the conquering Seanchan view the requisite chaotic-evil “mooks” following a Dark Lord as the real enemies. In a notable difference, we also get the varying perspectives of these “others” through their own voices. They talk amongst themselves and share their innermost thoughts, giving meaning and depth to their customs and beliefs. Turns out, they don’t even all think alike! Sure, there’s a great deal of “racial ventriloquism” going on. And Wheel of Time has other problems, namely a contradictory meshing of vastly empowered gender roles for women alongside a contradictory streak of sexism. But the nuance in diversity is certainly a step in the right direction.

And then of course, there’s George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire. If you’re acquainted with the books, you got that uneasy feeling of “otherness” upon first reading about the lands beyond Westeros, coming upon Dothraki, the people of Qarth, and elsewhere in Essos. Certainly in this grim dark fantasy, the citizens of Westeros are no saints: they can be terribly regressive, ignoble and prone to all sorts of nefarious acts. But even they seem to pale in comparison (pardon the pun) to the sheer savagery of the Dothraki, who kill for pleasure and rape anything that moves, or the utter brutality practiced in Slaver’s Bay, where those in bondage are treated as less than animals and killed on a whim. Westeros has its share of religious septons and drowned gods, but it is the East that is filled with wizards and a Red God who demands human sacrifices. For all its faults, Westeros has at least outlawed slavery. And it is again in the East where Varys is castrated and entire armies of eunuchs can be found in The Unsullied.

Even more troublesome, unlike Jordan’s Seanchan, almost every perception of this Eastern world in earlier books is told through the storyline of the pale-haired young innocent heroine Daenerys Targaryen. It is her tale we’re following, as she is sold by her brother to the Central Asian-Mongolian derived Dothraki as a bride for their leader. From there on, we follow along as Daenerys makes her way from one exotic locale to the other. And we immediately become aware of one thing: even if these Eastern lands are more wealthy and perhaps even much more learned, she’s still somehow better than the people and cultures she encounters.

Like a 19th-century colonizer carrying the White Man’s Burden, Daenerys is aghast at the customs she encounters–and is determined to do something about it. She tries to put a stop to the Dothraki’s use of rape as a weapon of war. She destroys the despotic wizards of Qarth. And when she comes across Slaver’s Bay, she burns up the “Middle Eastern-ish” slave traders and sets upon a crusade as the “great white emancipator”–freeing city after city and breaking the bonds of the enslaved through blood and fire.

If reading all of this in the books was uncomfortable, it was only magnified by HBO’s adaptation–which made the exotic Essos more “othered” than we had possibly imagined. As comedian Aamer Rahman pointed out back in 2013 in his rather bluntly put article titled “Daenerys’ Whole Storyline on Game of Thrones is Messed Up,” the visual image of a dark-skinned savage Khal Drogo raping the pale-haired innocent Daenerys every night “like a hound takes a bitch” is a lasting image.

And of course, let’s not forget the very first episode of the series which featured a troupe of all-black women Dothraki dancers gyrating in exaggerated sexual frenzy—who I’ve come to dub the Dothraki Twerk Team. Don’t get me wrong, twerking is a wonderful form of amazing expressive dance. But given the dearth of black women in the series, their muted, eroticized bodies stood out starkly on the screen. Then again, in GRRM’s universe all the recorded black people are crammed into a place called the Summer Isles—and are known for their nautical prowess, archery skills and rather uninhibited sexual mores.

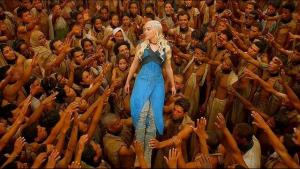

Daenerys’s role as the “great emancipator” is also played up to great effect, and has become a staple of the show’s recent plotline. In this cinematic version of events, Daenerys curiously remains so pale she never seems to tan under the scorching sun, and is often hailed like Lincoln entering Richmond by throngs of slaves. In the books, the slaves of Yunkai are actually described as quite diverse; but being filmed in Morocco, here they mostly appear as swarthy extras with skin-tones ranging from brown to black.

In the Season 3 finale the producers blatantly play up this contrast in a way that seems hardly unintentional, giving us a shot of a milk-pale Daenerys that stands out so much in this swarthy crowd that as the camera pans high into the sky she becomes a white dot–a sharp bit of light in a sea of dark bodies. It’s a full frontal dose of “othering”: all the traits common to the exotic, backwards tyrannical East, with a white saviour figure to boot, who sets about the task of colonization for the betterment of the swarthy locals.

The books admittedly present these events without hammering you over the head with it. And (don’t want to give away any spoilers) these colonial ventures eventually run into a few snags. But the main themes remain the same. And the depictions of the East, even compared to the less-than-flattering ones of Westeros, are still filled with Orientalist tropes and imagery. As these “others” never speak for themselves, what we get is a Fodor’s guide to Essos narrated through the storyline of the fair-haired Westerner; and thus her gaze becomes our own.

Part 3 of this series talks about how to avoid “othering” and racialisation in fantasy and SFF.

_____________________________________________________

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

_________________________________________________

Read more by Phenderson Djeli Clark Find him on Twitter @pdjeliclark

Read more by Phenderson Djeli Clark

- Oh Come All Ye White Saviors (mediadiversified.org)

- The ‘N’ word through the ages: The madness of HP Lovecraft (mediadiversified.org)

- Dieselpunk: Myth and Metaphor (mediadiversified.org)

Leave a comment