by Micah Yongo

Cue the credits, then the music, and our numbed seats rise slowly in unison, and a room of strangers together arch their spines, stretch their legs, and spread their arms, as though for flight, as the cosy dimness finally lifts and ushers us back to reality with the sated sigh of having been, for a couple of hours or more, well entertained.

Glad that’s over,” she says.

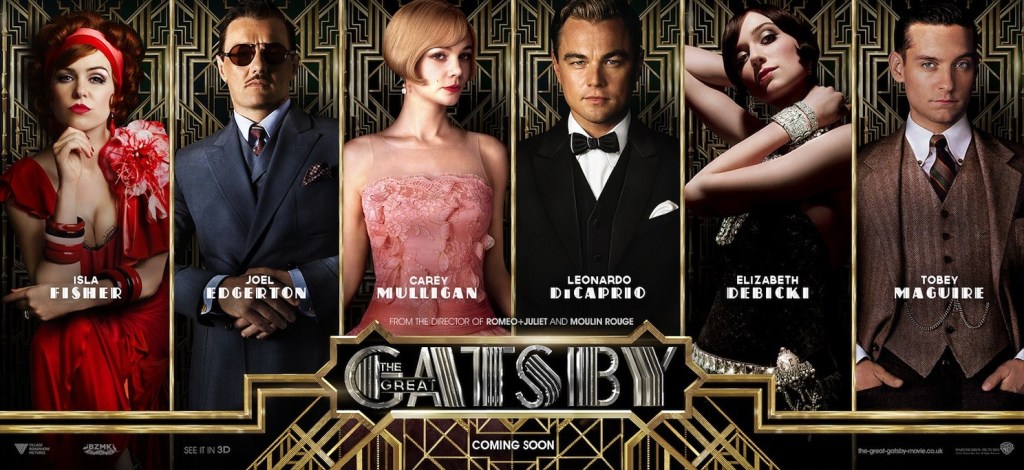

Which yanks my gaze sideways, squinting. We’ve just finished watching Baz Luhrmann’s admittedly somewhat trippy rendering of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. A work, apparently, not too far from memoir for that famous author, who’s said to have himself gorged on the heady excesses of 1920s New Jersey and later, Paris, during what he affectionately – with the kindly back-cast gaze of nostalgia – termed ‘the jazz age’. A decade in which, with the feigned austerity of prohibition finally put aside, upper class America abandoned itself to a kind of frantic hedonism – parties, alcohol, orgies – high society collapsing into a roiling hungry din, one, I thought, well captured by the drunkenly swooping camera of Luhrmann, zooming from close up to vista and back again like some crazed cosmic wrecking ball, all to the backbeat of throbbing rap/jazz fusions; Jay Z and the Charleston; forgotten past to lively present, together rendered in cartoonishly rich toffee-sweet Technicolor. The Wizard of Oz with extra vodka.

Now, granted the narrative grows a little sketchy in places and the characterisation is nigh on non-existent but the whole piece nonetheless manages to carry, or so I thought, a visceral and zeitgeisty punch that makes the watching fairly fun.

Nah, I lost interest after half an hour,” my wife shrugs, “didn’t care about the characters. There was no story.”

Which are all valid points, and yet seem, at least to me, following so cinematic an experience, borderline heretical. But then I suppose that’s the thing. I mean, I like story and characters too, but they’re not so big a deal to me if things like spectacle or suspense are well enough deployed, or if some narrative convention or norm is being subverted in a way that’s interesting, which is why I love David Lynch, and why a film like Christopher Nolan’s Memento will always be a favourite. My hook, you see, when I sit down to watch a film, or read a book, or see a play, is sort of intellectual. That’s just where I like to be tickled. Whereas my wife’s is, mostly, relational. She wants to be made to feel, I prefer to be made to think. All of which means one simple thing: The very experience I was loving for the sheer bold novelty of Luhrmann’s visual oeuvre, she, sitting right beside me, was hating. Which gets one to thinking.

In her book, The Human Condition, Nina Rosenstand refers to humanity as ‘The Storytelling Animal.’ The basic idea being that the weight of all our abilities as a species – our intellect, our consciousness of time, our awareness of finitude, of coming death – has given us a capacity for discerning meaning that is more than just an aptitude, it’s also an appetite. It’s not just that we can figure things out, we need to. It’s an itch. Which is kind of important. Because it compels us to learn, to develop frameworks in which to order things, patterns, correlations, whether of the sounds and enunciations we call speech, or cosmic cycles; the times and seasons of the year, the position of the moon, whatever – understanding of all these things and more is achieved through our being able to build one observation upon another until our world takes on a knowable shape, a form, a character we can safely interact with. Not only this, in order to reconcile ourselves with our own existence we find it necessary too for our lives to also have a shape, to be knowable, to have, yes, meaning. This is why we tend to conceive of ourselves through narrative. Why we all have, must have, to our own minds at least, an understandable story. Beginning, middle, end. This leading to that. History and legacy.

In fact, if you really think of it, it’s not the calamities of life that really trouble us so much as the unanswered ‘why?’ that will often accompany them. Meaninglessness is the thing we really fear; Chaos, as the Greek poets had it. And so since then and before, every age and people has told stories; fables, aural and written, to combat this Chaos, eliminate this sense of disorder, and persuade us against the world’s ambivalence. To give it meaning. In short, fiction has and always has had a function, one higher than mere entertainment, and, that being the case, a duty also. Which brings us to my wife’s original displeasure. Her feeling that Luhrmann had abdicated this unspoken duty, or at least failed to adequately perform it. As she so pointedly put it; ‘there was no story’.

Now, I’m going to say that these are words worth pondering; because she is not really lamenting the absence of characters and story per se, but rather something, to her as viewer, in many ways equitable: That there was no character or narrative with which she, personally, could identify. And herein lies the rub. For it is this need to identify – recognised by both artist and audience, author and reader, actor and viewer – that ultimately confers the power and import of any story. The thing being that every narrative, if it is to have meaning, at least to you personally, is really, in some complicated way, about you, or me, the paying punter. About what it is to be human. As David Foster Wallace once wrote: ‘We’re each the hero of our own drama.’

And so it’s with this in mind that the novelist, screenwriter, actor or director seeks to create and present characters that can be in some way deemed ‘sympathetic,’ designed to become surrogate and vehicle for the hopes, hurts and interests of his or her audience. A means through which we can be convincingly consoled, or absolved. Champion and scapegoat. Something we can invest in and care about (witness the more fanatic response to soap actors, referred to, by their fans, by the name of their character, not their actual name) because they are, in some way, one of us, having some struggle or emotion or challenge we can recognise.

And this really is where things get juicy. For not only can story lend a sense of shape or form to life that in some way comforts or edifies us, it, if done well, having gained the trust of its audience, can go on to also prescribe that shape, transfigure it. Lay a bridge between what is and what ought to be. In other words, good stories, perhaps the best stories, can teach, convey an argument, illustrate a point, direct its audience. Little wonder Austrian philosopher, Ivan Illich, once said;

If you want to change a society, then you have to tell an alternative story.” [1]

In fact the 17th century Scottish politician, Andrew Fletcher, went further, extending this thought to include other expressions of art when he said;

Let me write the songs of a nation, and I don’t care who writes its laws.” [2]

Chinua Achebe Things Fall Apart (The African Trilogy)

Chinua Achebe Things Fall Apart (The African Trilogy)

And there’d be more than a few examples – ranging from a book like Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart – of courageous and beautiful pieces of art that have changed the heart of those with whom they have engaged. Which is all to say there is a valid reason, on some less than conscious level, these things matter so much to us.

Why comic book fans argue so vehemently about the latest film adaptation of the Superman franchise. And why how Baz Luhrmann renders The Great Gatsby on screen matters so much to the audience who will see it. These things are, in a way, the canons of our culture.

Now, all this brings us to a dilemma; the other concern of the artist, the one I, out the corner of my eye, look out for when sitting down before whichever medium – film, theatre, dance etc. – I’ve chosen to be entertained by. I’m talking about the artist’s aim to not only convey her truth or ‘message’, whatever that message might be, but to also advance the form she is using to communicate it. Her goal, in this instance – unlike the weighty works of Lee, Orwell and Achebe mentioned above – is not to change or challenge her audience, and thereby her society, but rather her medium, the norms and conventions of her art. To – as was once said of Michael Jordan – change the game.

This is what we call innovation. And this is the thing – watching The Great Gatsby – that was intriguing me, and not my wife. It wasn’t necessarily the story that was so exciting as much as the way Luhrmann was telling it, or to be precise, filming it.

Luhrmann, it needn’t be said, is an unusual filmmaker, at least in this day and age. His past works – La Boheme, Romeo + Juliet, Moulin Rouge – reveal a heightened and theatrical sensibility, a taste for melodrama (in the original sense of the word), whilst the man himself makes no bones about what he seeks to impose on his audience when they sit down to watch something he’s made. As he once put it; ‘In my films, I’m demanding that you say, “Are you in or are you out?”’1

‘Participatory cinema’ as he and others have called it – an approach aimed at arranging the medium, as much as possible, around the viewer in order to synthesise their world with the one in which the narrative is taking place2. Which means yes, there was no hip-hop music in 1920s New Jersey, just as there were no guns in 14th century Verona. But the game here is not to faithfully depict the milieu in which the story plays out, but to convey it, and more specifically, convey it to you, us, sitting here in our 21st century post post-modernism. Something Luhrmann goes about achieving through what is, in effect, an elaborate kind of visual surround-sound simile, 3D and all.

And so for the tingle-thump rhythms and staccato vocals of Jay Z, read the 1920s jazz of a burgeoning black middle-class, dancing in the throes of the Harlem Renaissance, where the music itself – improvisational, unpredictable, agile – is both offspring and signifier for a world bubbling amid shifting fault lines of class and culture. A world in which, to quote the Langston Hughes poem of the time (I, Too) African Americans were beginning to take their place ‘at the table’ and exert their own unique influence on popular American culture. The economy was booming, the straitening effects of prohibition were coming to an end, the first world war was a receding memory in whose wake industrialization was rapidly expanding, there was mass immigration from overseas and The Great Migration of African Americans from the south, all churning a melting pot of change that left old societal norms up for grabs.

In other words, a stiff and sterile period in history this was not, yet to have filmed Gatsby in a more traditional way, a naturalistic way, for Luhrmann, would have rendered it so. And so the man, to his credit, unwilling to forfeit truth for conventional realism, chose instead to innovate i.e. to literally make new; something the American novelist and essayist, Anais Nin, once claimed to be the very ‘function of art’. A function I couldn’t help feeling Luhrmann accomplished pretty well.

Now, you may say, and I’d understand if you did, that judged in light of my wife’s preference for character and story and all, as has been explained, it represents (teaching us to identify with our fellow man, connecting us with concerns to which we would be otherwise ignorant, advancing our moral rectitude), that it would seem – this more aesthetic preference of mine – something less noble, of lesser human value. Superficial. It’s pretty self-referential after all, unconcerned perhaps with improving the mores of society. It could even be said to be insular, self-centred. I mean, we’re no longer talking about how art can change the world, we’re discussing how art can change art. Which seems trite in comparison. The emphasis no longer what the story is, but the way it’s told. Style over content. Form over substance.

But before you clamber so readily atop your high ground I’d ask you to consider a few things. That perhaps this seemingly unimportant concern – the desire to innovate – to take the way a thing is and turn it this way and that, to, in short, experiment, is as purely human as the desire and need to speak, as much a part of us as our values, indeed, is one of our values. And perhaps it is with this, the impulse to innovate, to pioneer, that I – as I sit watching Gatsby, or Mulholland Drive or some other unconventional film – identify. And if so this is no small or trite thing, this restless jaunty spirit of invention and enterprise has given us the wheel, steam engines, the iPod. It is, and has proven itself to be, as big a part of our progress as the societal concerns Messrs Achebe and Orwell took aim at. The advancing of our humanity, our capacity to feel, is of no greater value than the advancing of our art, our ability to imagine, innovate, invent. And it’d be a brave man or woman who’d be bold enough to say that one can trump the other.

And so I submit, dear reader, that film, books, whatever, cannot just be about finding new stories to tell, but also exploring new ways to tell them. For in the same way in which the stories of characters we identify with speak to us, to what it is to be human, so does our witnessing of those stories that take on new forms. They speak to us of breaking barriers and conventions, of finding new and interesting ways to do things, of evolving. They speak to us of being bold enough to explore, to be creative. That’s what made Picasso inspiring, so too Mozart, so too Kubrick, and every other artist that has ever been radical or courageous enough, for a moment at least, to discard convention and seek a new way. Because to do so is as much a part of our humanity as anything else. We are born to create, innovate, imagine.

And so perhaps my wife is right, she usually is. The characters in The Great Gatsby were poorly rendered, the narrative woefully expressed, the events a little incoherent. But there’s more to film and art, as there is to life, than these conventions, regardless of their comforts. There’s the alternative. The unconventional. The experimental. Different. Risky. The way of Picasso, of Mozart, and of Kubrick, and so too – I’d stretch my argument to say – of every activist or humanitarian who has ever allowed their discontent with the established status quo to cause them, in the words of one great man, to ‘have a dream’. To conceive a new way for things to be. It wasn’t just their compassion, their ability to empathise or identify with others, it was also their capacity to imagine new realities, possibilities beyond the present norm, to pursue something different.

And it is both these two things – to relate and innovate – that make art, in all its many forms, important, powerful even. Because these two values – to feel and to think, to connect and to imagine, to empathise and innovate – are what reveal the best of us. And to see them expressed, both and each of them, in film, in photography, in song or whatever else, is like having a TV commercial advertising our better selves played to us, reminding us of the quintessential attributes of our very humanity.

And so perhaps it is this truth Luhrmann doffs his cap to with his own inventive style, in several scenes of The Great Gatsby tacitly referencing the Harlem Renaissance, acknowledging the role, even then, the arts (literature, poetry, music) had to play in the progress that was made, and in so doing providing a clue with which to answer that old and oft repeated question: Why does art matter?

And as for the answer? Why does art matter? Why does it matter that you write, act, paint, photograph, sculpt, dance, invent or whatever else? Well, put simply, it matters for the same reason it did during those tumultuous days in 1920s New York.

It matters because art does not just imitate life, it also reminds us how to live it.

- Taken from a really interesting interview with Luhrmann in which he discusses the ‘heightened theatrical cinematic language,’ he prefers, and how he seeks to use this artifice ‘as a big lie that reveals a big truth.’

- It’s an approach it could be argued has its roots in phenomenology, a branch of philosophy concerned with the study of subjective experience. There’s some interesting work out there right now applying the principles of this concept to design and art. This talk captures the idea well:-

Related

Tracklist For “The Great Gatsby” Soundtrack Features New Music From Jay-Z, Beyonce, Andre 3000

Micah Yongo writes about creativity, literature, culture and film. He is part of the Writers of Colour collective and has been published at mediadiversified.org. When he isn’t busy writing articles he can be found, with knuckle to chin, at his blog Thoughthouse or else working on his own fiction writing. Micah tweets as @micahyongo.

This piece was edited by Désirée Wariaro

Leave a reply to Carrie Mulligan Cancel reply