In the autumn of 2001, photos of the stoned, dirty-looking white guys in the Strokes are plastered across my bedroom wall and I brag about getting great tickets to see their sold out show. In art class the TV is on mute while we paint and glance with teenaged disbelief at the tiny people throwing themselves out into the Manhattan air from the Twin Towers. Someone puts on Outkast’s “B.O.B.” but our teacher doesn’t like it, so the familiar symphony of Beyoncé, Kelly and Michelle starts to fill the classroom instead and the teacher is lulled back into narrating memories of trips to New York while staring at the TV.

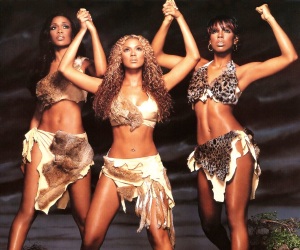

After classes my friends and I often buy snacks at McDonald’s while other kids sit and smoke by the artsy cafés. Then we take the underground to my friend Sasha’s place to watch music videos on MTV. While we look at Destiny’s Child in the “Survivor” video Sasha starts talking about Beyoncé’s stomach.

“Beyoncé is fat,” Sasha says. “Her stomach wobbles.”

I look at Beyoncé’s stomach to see if I agree with Sasha but I can’t decide — all I see is a group of pretty girls singing in harmony about overcoming obstacles — so I just ignore her. It feels like I should care as much as Sasha about Beyoncé’s stomach, but I am a late developer and those kind of thoughts have not started swirling around my consciousness yet.

I look at Beyoncé’s stomach to see if I agree with Sasha but I can’t decide — all I see is a group of pretty girls singing in harmony about overcoming obstacles — so I just ignore her. It feels like I should care as much as Sasha about Beyoncé’s stomach, but I am a late developer and those kind of thoughts have not started swirling around my consciousness yet.

When the video ends Sasha looks over at me while I take a tentative sip of my Fanta. “Do you prefer Beyoncé or Kelly?” she asks. I don’t like her question.

“Eh, they seem equally talented?” I suggest. Remembering Beyoncé’s stomach I quickly add, “Kelly has a perfect stomach, actually.”

“Oh, how can you not like Beyoncé the most? I mean, she’s black but doesn’t even look like a black person.”

“What does that even mean?” I say, wanting to get angry at her but stopping myself.

“I just love Beyoncé,” says Sasha, changing the channel to a reality show. “She inspires me.”

Sitting next to my friend I start seeing how powerful black female beauty is as a commodity, and how our bodies can get turned against us.

As adulthood comes closer, Sasha and I are less focused on developing our independent ideas and skills and more interested in Beyoncé’s stomach, Beyoncé’s hair, Beyoncé’s moves and Beyoncé’s work ethic. Other girls around us are equally mesmerised and clone themselves into her likeness. The older I get the more I am sucked backwards into the parallel world other teenagers and adults live in where Beyoncé is everyone’s default black fantasy friend and default black fantasy lover.

After seeing Formation for the first time I was in shock. I felt really happy and slightly crazy as I sat in bed watching the video repeatedly, maybe twenty times. I couldn’t believe Beyoncé had done the impossible and spoken directly to me as a black woman. Then Lemonade made me feel joy again after weeks of crying. As I listened to the recognisable lines about sadness and grief in Warsan Shire’s poetry that slid effortlessly into Bey’s soulful cadence, I fell so deeply in love with all black women who fearlessly voiced their opinions.

After seeing Formation for the first time I was in shock. I felt really happy and slightly crazy as I sat in bed watching the video repeatedly, maybe twenty times. I couldn’t believe Beyoncé had done the impossible and spoken directly to me as a black woman. Then Lemonade made me feel joy again after weeks of crying. As I listened to the recognisable lines about sadness and grief in Warsan Shire’s poetry that slid effortlessly into Bey’s soulful cadence, I fell so deeply in love with all black women who fearlessly voiced their opinions.

I hadn’t properly assessed what it was that I needed in my life, and that was to be heard.

I found it a work of so much heart, and so heartening, that it has changed me forever. I don’t believe another black woman, anywhere, who says they don’t feel the same kind of love for Bey somewhere in their soul that I now feel (no matter how prominent they are).

For people who thought that every inch of Beyoncé’s artistry had been revealed, and perhaps made up their minds about her years ago, maybe even as far back in time as Survivor, the viewing of Lemonade must have been enervating.

It’s nice to see that nothing’s changed when a work of art by a black woman comes under the same scrutiny as her appearance. Certain people probably stopped looking after the camera panned in on Beyoncé’s flared nostrils, her smooshed-up face growling in anger, in the hell-hath-no-fury scene of the song “Don’t Hurt Yourself”, thinking it was just a stereotypical chapter in an overly sentimental story. And they probably felt Formation was a publicity stunt gone overboard.

Everyone of a certain age grew up examining her videos. Among people (like myself) born in the 80s and 90s, the so-called “millennial generation”, she is, presumably, one of the most recognisable celebrities. “Millennials” have grown up conflating black women and casual entertainment, which has made me feel particularly uneasy whenever I have gone on a date with someone for the first time or am romantically attracted to someone, and am also looking for signs of whether the person might think I’m some sort of sensual “Cater 2 U” woman. This is often the case whether they are black, beige or brown — so I purposely wear loose dresses, eat ice cream, and wear big glasses that cover my face.

I can still remember a time when seeing myself in the mirror didn’t necessitate self-consciousness, long before I’d heard anyone say anything about Beyoncé’s stomach. I’m satisfied with my appearance, but I don’t post any selfies, partly because the need I had to define my self-worth to others faded away, partly because I saw how I was comparing myself too much to popular black beauty vloggers on YouTube and other people with a lot of social capital.

Keeping up with famous and beautiful people requires a lot, a lot, a lot of work and money. Hours every day spent painting, pressing, rubbing, washing, shaving, patting, tweezing, exercising until faint, going hungry and checking your reflection. I did that for years, because I thought I couldn’t go back to being ignored and obese, and it made me really shallow. At certain times I’ve felt like there was a chance I could become addicted to plastic surgery and go into massive debt if I didn’t stop caring about showing others how special I thought I looked in some new makeup in selfie after selfie. I understand how using makeup to your advantage can be really fruitful, something a lot of famous black women demonstrate with their wealth and influence, but beauty culture is toxic when it persuades women to strive towards anesthetizing ourselves by changing everything about our natural bodies, instead of staying in the confusion and doubt of our minds. Looking unattractive or being overweight doesn’t contribute to me automatically disliking myself; it’s the people who critique how Beyoncé’s stomach “wobbles”, who regularly convince me that getting my eyebrows on fleek is crucial to my survival.

Still, I hate it when it is suggested that taking selfies is purely shallow, or that caring about makeup is insignificant. That denigrates my way of dealing with our beauty-obsessed world, where my self-worth as a black woman is tied to my appearance, to superficial greed. White women have a gigantic revolving wardrobe of different identities at their disposal, ranging from Lena Dunham’s barefaced, experimental androgyny to Kim K’s high gloss femininity to Hillary Clinton’s soft blonde pragmatism. Black women have to make a difficult choice between being either hypersexualised or ignored just to survive.

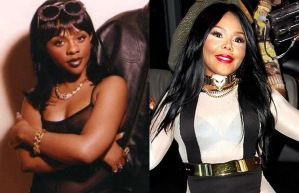

It’s interesting to see what has happened to an accomplished black artist like Lil’ Kim, a woman who used to defy gender boundaries by inviting us to “suck [her] dick”. She has now been pressurised into conformity, bleaching and remoulding her once dark, black features to be as white as possible. By changing her appearance in this way, Lil’ Kim is open about where her interests and beliefs lie. She is a black woman penetrated by white power.

It’s interesting to see what has happened to an accomplished black artist like Lil’ Kim, a woman who used to defy gender boundaries by inviting us to “suck [her] dick”. She has now been pressurised into conformity, bleaching and remoulding her once dark, black features to be as white as possible. By changing her appearance in this way, Lil’ Kim is open about where her interests and beliefs lie. She is a black woman penetrated by white power.

Her internalised colorism is relatable. Even as a mixed-race black woman with European features, I often wish my skin colour were as invisible as a white girl’s. It is a double bind for a black woman to care about her appearance; either we are popular and sexualised or we are alone and ugly. In her memoir, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, the former slave Harriet Jacobs situated the physical beauty of black women as a harmful factor that ”hastens [our] degradation”, in stark contrast to the normalised physical attractiveness of white women. When I became a full member of the cult of prettiness I gradually stopped eating. My body shrank and I got more attention.

Statistics on rape and assault say that racially ambiguous women, closely followed by black women, are much more likely than white women to be abused in America. Those statistics suck me right back into the dark times when men and women of all races have elbowed themselves into my personal space and greedily used me to fulfil their selfish needs, like a pet or a Black girl sex doll.

Although political black music is a paradigm-shifting cornerstone of popular culture, a black woman manifesting her freedom is such an anathema that we always scramble to find faults in her. The trivialities in Beyoncé’s orbit — the style choices, messy family matters, and provocative song lyrics — are examined more closely because of her gender as well as her race. It isn’t a coincidence that it took Beyoncé decades of work and albums to express herself as anarchically as Prince, a musician who exerted his independence from the earliest stage of his career. The scrutiny put on a famous black woman is particularly apparent in comparison to the freedom of artistic expression granted to famous men. It’s hard to fathom the bravery of Beyoncé, but it’s clear that the precision with which she publicly unwinds her politics is a matter of necessity.

Even in 2016, it’s hard to be a black woman; just being yourself carries huge consequences, which can make Lemonade a dissonant viewing experience. It feels like we’ll always keep running, using our immense creativity to further our rebellion, although we will never really escape our addiction to whiteness.

Even in 2016, it’s hard to be a black woman; just being yourself carries huge consequences, which can make Lemonade a dissonant viewing experience. It feels like we’ll always keep running, using our immense creativity to further our rebellion, although we will never really escape our addiction to whiteness.

I hope a fundamental change will occur in our treatment of all black women in our daily lives — including those who are hypersexualized and those who are strange, outspoken and free — before we become a society where everyone has to abandon their identity for the creepy miasma of beauty culture. A woman attempting to run away from her oppressor is a scary thought to people who would rather she stayed warmly maternal, enticing and, ultimately, unfree. In many ways, Beyoncé has freed herself and her body of servitude, paving the way for the rest of us to follow.

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Read more by Désirée Wariaro here.

Read more by Désirée Wariaro here.

If you enjoyed reading this article, help us continue to provide more! Media Diversified is 100% reader-funded – you can subscribe for as little as £5 per month here

I can’t abide anymore of the worship of this woman. She doesn’t represent me or is not a figure of black womanhood that me or black women should look up to precisely because of the reasons you’ve written about in this article. She has been bred from birth to be a pop star. She has been taught to distance herself from the black community except as a means to further her career. She has transcended all of the travails that the average black person has to deal with because of her pop tart status. I claim no connection with this woman. If anything, though Solange has been brought up the same way, any admiration I have would be for her more than Bey. Solange has created a space that is all her own separate from Bey and her mother that seems to be defiantly her own. She embraces her natural hair and isn’t beholden to any pressures of catering to becoming a sexualized tool of the music industry. I may be a little harsh in my disdain but I have a problem with any worship from not only the black/brown diaspora but from white people as well. This is a problem that begs more analysis and discourse. Thanks.

LikeLike

I thoroughly enjoyed this article and a fresh perspective on Beyoncé as it relates to women, black women and our expression/interpretation of art. I recall a white women saying Beyoncé should put on some clothes on stage after the Superbowl performance. She’s not setting a good example for her daughter. My response was yes, she should put on some clothes like CHER, BRITTANY SPEARS, MILEY CYRUS, MADONNA, AND ALL OF THE BALLERINAS OF THE WORLD. 😊

LikeLike