by Rajeev Balasubramanyam Follow @Rajeevbalasu

An insecure, bullied child in darkest, whitest Lancashire, I wanted two things: to fit in, and to be weird.

Fitting in was never a realistic proposition. I was the only non-white kid for miles around; far shorter than everyone else, barely knew the rules of football (I loved cricket), left-handed, South Indian (a freakery insufficient to stop them calling me a Paki), and highly sensitive. This wasn’t the sort of weird I wanted to be.

When I say I wanted to fit in, I didn’t actually want to be like the white kids around me who, as we grew older, became obsessed with indie rock and shabby, baggy clothes. I just wanted them to stop picking on me. They probably were weird – I’m sure my parents found them weird – but it wasn’t the kind of weird I could relate to. All I could do was imitate and hope not to be found out.

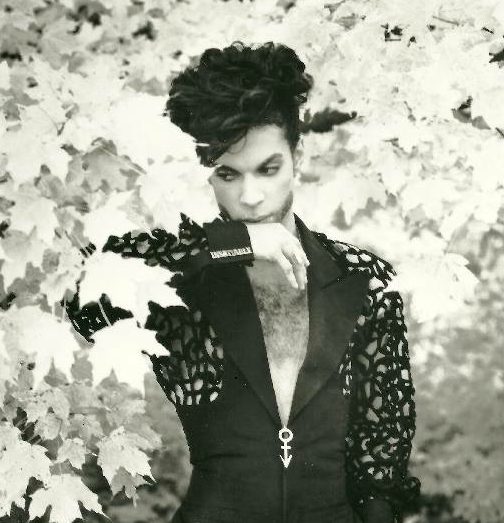

What I wanted was to be weird like Prince.

Outlandish, unbearably confident, polysexually irresistible at five feet two inches tall and with eyes like a Disney Princess’s, avant-garde in his own way, so radically himself, Prince was moving too fast, rising too fast, loved himself too much that nobody, it seemed, could hurt him.

Outlandish, unbearably confident, polysexually irresistible at five feet two inches tall and with eyes like a Disney Princess’s, avant-garde in his own way, so radically himself, Prince was moving too fast, rising too fast, loved himself too much that nobody, it seemed, could hurt him.

As I got older, it became apparent that this was what I most lacked: self-love, self-esteem, that essential, live-giving force. And it wasn’t Prince’s weirdness or coolness I envied most. It was this. When I listened to his voice I could hear it, but it was lost in me, hidden by terror and doubt, by the timidity of my own voice. His voice was free from fear, and when I listened carefully I realised that no matter what he was singing about, and usually, back then, it was sex, there was always this feeling of ecstasy, of celebration and transcendence. This was so attractive to me as a child because I was trapped inside an aggressively atheist, cynical world. Everything my peers did, they did in a secular way, and in my home life, religion was close to dirty word, something for fools. But Prince sang openly of God, and with the same breath that he used to sing about sex; they even seemed to be the same thing to him, a form of holy communion.

There’s a song called ‘The Holy River’, on Emancipation, in which he describes that process of change we all have to go through to move from a state of misery to a state of grace. It’s an age old story, the spiritual journey, but Prince, writing in the second person, made it sound possible. His philosophy of life was faith-based, positive not in the self-deluding or self-denying way that is becoming so common in the age of corporate spirituality, but in the manner of the old mystics, of sufi saints and bodhisattvas.

This is what he did. He showed us that life didn’t have to be a morose, terrifying experience, that artists didn’t have to be perpetually tortured, self-destructive, addicted, and depressive. It’s something I’ve remembered over the last weeks, listening to his albums again, mourning but feeling unable to remain unhappy for too long. Prince’s music doesn’t allow you to be unhappy. He insists you celebrate life with him, and his insistence is infectious, irresistible. Life and art, his music shows, can be positive, joyful, and transcendent of misery while remaining transgressive, avant garde, complex, and honest.

It’s a repudiation of so much that I learned in my teens from my peers and my schooling, from near all modern European thought where the intellect was everything and spirituality scorned, a suicidal intellectual leap that has become synonymous with progress. It was there in existentialist novels; it was there when rock stars shot themselves even though they were living everyone else’s dream. The message was that if one wanted to be an artist, to live distinct from ‘the mainstream’, one had to be unhappy. Happiness, like spirituality and advertising, was a photoshopped corporate illusion.

For Prince, spirituality was his source, the holy river, the stream of life, and he didn’t need an argument to prove it because he could feel it and so could we when we listened to him. Prince showed us that faith could overcome misery, and it wasn’t as if he was above suffering. He was human, estranged from his father, had lost two children, and as we now know, was in chronic pain due to damage to his hip after years of dancing in stilettos. But his philosophy of life was always positive and it was there, unfaltering, in the music that seemed to pour out of him.

In his final years, I read, he had become quite ascetic in his habits; vegetarian, celibate, eating and drinking very little, working incessantly in the name of service. Had he lived to be an old man, I like to think he would have ended up as a monk, slowly transcending all the flash and glamour of his earlier life. But he didn’t, and though I’m heartbroken this happened, I’m left with a deep feeling of gratitude. I grew up in a cynical, unhappy world, and Prince showed me the way out.

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Rajeev Balasubramanyam has a PhD in English, and holds degrees from Oxford and Cambridge Universities. His first novel, In Beautiful Disguises (Bloomsbury, 2000), won a Betty Trask Prize and was nominated for the Guardian First Fiction Prize. In 2004 he was awarded the Clarissa Luard Prize for the best British writer under the age of 35. His second novel, The Dreamer (HarperCollins), was published to critical acclaim in 2010, based on his Ian St. James Award-winning story of the same title. His newest book, STARSTRUCK, is a novel in ten parts currently serialised by the Pigeonhole ‘starring’ 10 different celebrities, including David Beckham, George Bush (Sr.), Freddie Mercury, Michael Jackson, Prince Harry and others. You can sign up at https://thepigeonhole.com/books/starstruck. Follow Rajeev on: @Rajeevbalasu

The Morning Papers is a collection of pieces about Prince. In April, Music lost a singer and musician, but we writers also lost a poet. Whether it was his characters, or his line by line precision and intimacy; Prince was every bit the alchemist of words as well as music. In this space writers were invited to talk about the artist, in whatever context they desired. Curated by Sharmila Chauhan.

The Morning Papers is a collection of pieces about Prince. In April, Music lost a singer and musician, but we writers also lost a poet. Whether it was his characters, or his line by line precision and intimacy; Prince was every bit the alchemist of words as well as music. In this space writers were invited to talk about the artist, in whatever context they desired. Curated by Sharmila Chauhan.

Leave a comment