by Jagdish Patel Follow @jagdish_patel

In the UK, many photographers have used photography to examine their own identity, whether this identity rests in being black, their class, gender, sexuality or disability. In the period from the late 1960’s to the 1970’s many ‘white’ photographers also explored the social changes in Britain. This was a period when Britain began to lose its Empire, when decay and industrial decline were prevalent, which led to conflicts (industrial, racial and in Ireland) and the impact of immigration saw a rising tide of overt racism.

John Roberts identifies this shift on the ‘radicalisation of a younger generation of photographers in the wake of May 1968, and the entry of working class and lower middle class students into higher education with no attachment to the virtues of high culture’. (Roberts, 1998, pp145) In his view this led to ‘a powerful radicalisation of the critique and realism, and as such a powerful hegemony.’ (Roberts, 1998)

The works of Bill Brandt, Chris Killip, Graham Smith, Ray Jones, Ian Berry, Chris Steel Perkins and Brian Griffiths all touched upon the ‘national crisis of identity’ (Mellor, 2007). The images being produced at the time were very much in a documentary tradition. Black photographers such as Vanley Burke, Ahmet Francis, and Horace Ove also worked in a similar style, and therefore the question is, what constitutes black photography during this period? Is it just that the photographers are black, or is therefore something specific in the style of the photography?[1]

In ‘Photographing Handsworth’ (Connell, 2012), Kieran Connell compares the studio based self portrait project of Derek Bishton, Brian Homer and John Reardon to the documentary realism of Vanley Burke and Pogus Caesar. All of the photographers wanted to capture the everyday textures and realities of the local black communities in Handsworth, near Birmingham. ‘Handsworth has its share of problem.. but we were looking for images which challenged the simplistic arguments which blame certain sections of people for those problems’. (Bishton quoted in Connell, 2012) Connell notes, ‘For Burke, the recording of such stories is ‘vital’ not only, as in a conventional family album, in order to create visual mementos of important events, but also to ‘pass on the message about the experiences these people have had’. (Connell, 2012)

As he compares the different styles of images from the two projects, Connell notes that photographs which present the lives most sympathetically are those where the photographs are staged in the studio, or taken out of context of their daily lives, in factories, the streets or in the presence of police. In this sense the most authentic photographs are really not authentic at all. Once you add the elements of real life into the photographs, then the images are very difficult to separate from the usual images you would see in any newspaper. This is simply, one of the reasons why black photographers began to move away from the documentary style. For me, this point is highlighted in the book, ‘Black Britain – a photographic history’. (Gilroy, 2008), in which a document which charts the history of Black Britain, takes almost all the images from the Getty image library.

The decline in the popularity of documentary photography in photography schools also occurred for two other reasons. The first was the reappraisal of the reliability of documentary photography to document objective reality. As Roberts points out wriers such as John Tagg and Victor Burgin effectively used post-Althusserian and post-Structuralism analysis to question the relationship between the photograph as an object of objective realism and art as an object of subjective expression (Roberts 1998). Secondly, the influence of feminism and psychoanalytical theory. Stuart Hall’s own work in ‘Policing the Crisis’, resulted in many photographers rethinking how documentary photographs objectify its subjects. Many photographers therefore began to move the camera lens away from their subjects, shown by the work of Paul Graham and Nick Waplington.

As we can see, Hall’s argument that the 1980’s represented a ‘conjucture’ should also take into account wider developments within the practice of photography which affected both white and black photographers.

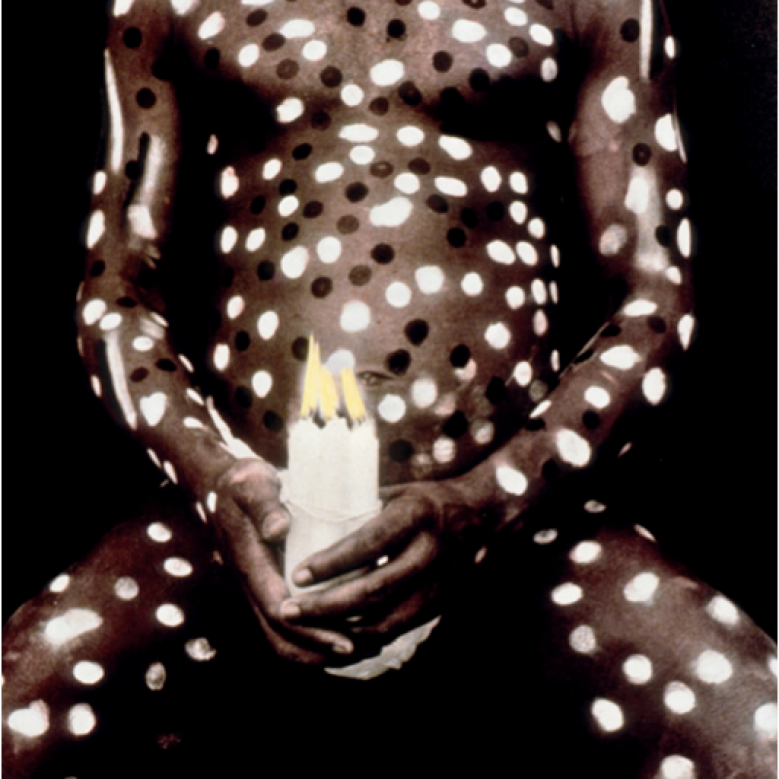

The writings of Stuart Hall have helped bring greater awareness of ‘race’ as a signifier. This has been widely written about through the comparison of the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe, and Romi Fani Kayode. Both are gay men exploring black male sexuality, and both men produce highly fetishised photograph of the black male nude. Fani Kayode reworks Mapplethorpes images through his references to his Yoruba heritage. There is no doubt that, part of the power of Kayode’s photographs rests in their relationship with the images of Mapplethorpe, which in turn relate to a series of images of masculinity from as far back as the work of Caravaggio. Hall argues that Mapplethorpe is ‘voyeurist’, whereas Fani-Kayode ‘subjectifies’ the black male. (Hall and Bailey in Wells, 2003)

For Kobena Mercer, Fani- Kayode’s heritage is crucial to his work, ‘born into a prominent Nigerian family in the prelude to political independence, Fani-Kayode grew up across three continents – Africa, Europe and America – during the three decades from the 1960s to the 1980s that saw the world transformed by the emergence of the postmodern and the postcolonial. His biography was thus shaped by the characteristic diasporic experiences of migration and dislocation, of trauma and separation, and of imaginative return’. (Kobena, 1999)

Fani Kayode is acutely aware of his background. When asked why he never displayed his work in Nigeria he explains, ‘As for Africa itself, if I managed to get an exhibition in say Lagos, I suspect riots would break out. I would certainly be charged with being a purveyor or corrupt and decadent Western values. However, sometime I think if I took my work into the dual areas, where life is still vigourously in touch with itself, and its roots, the reception might be more constructive’. (Fani Kayode quoted in Reid, 1997).

There are three lessons from Kayode works that are worth mentioning. The first is the ability of black artists to disrupt an iconic stereotype through references of their own background, secondly the impact of diaspora, which Kobena refers to ‘a rupture caused by dislocation and emigration’, (Kobena, 1999) and thirdly the ability of black photographers to question notions of modernity and tradition not just in the West but also, in the case of Fani-Kayode, in Nigeria.

It is interesting to compare the work of Fani Kayode to that of Mitra Tabrizian. Whereas the work of Fani Kayode mainly focuses upon the black body, Tabrizian places the gaze of the subject centrally in the images to make us question race, gender, and class. For example, in Tehran (2006) she constructs a large-scale town landscape in which the subjects seem to be conducting everyday business but without an apparent working infrastructure, lighting or roads. In ‘Leicestershire’ (2012), she uses ‘landscape’ and ‘documentary’ genres to address issues of migration, exile and the impact of post Fordist deindustrialisation by photographing former factory workers against the closed factories they once worked in.

Pollack notes that Tabrizian, ‘Across her many projects, which are often practices on photography as practices within it, we note. .. Tabrizian questions the masquerades which our identities and sexualities are currently but precariously held.. the game is not to strip the veil and expose the truth.. (but) to know what masks we wear, to define the texts we performs and to accept the necessity for critical knowledge’. (Tabrizian, 1990, p11)

Tabrizian’s work takes what Kobena earlier described as the ‘ruptures of migration’, and is able to engage both with the ideological background but also provide a commentary on how we construct the modernity. As Gilroy wrote ‘What was initially felt to be … the curse of homelessness or the curse of enforced exile … is reconstructed as the basis of a privileged standpoint from which certain useful and critical insights about the modern world become more likely.’ (Gilroy, 1998, pp111)

Although Hall seems to suggest that the more recent photographers are influenced by commercial factors, rather than social history and politics, I think we can show from Tabrizian’s work that this is not the case, but neither is the work weighted downs by racial signifiers. In his paper, ‘New Ethnicities’ (1989), Hall moved is own identity away from an essentialist black identity, but in the process he also moved away from many of the black community groups. [2]

It is important to recognise that although identity is fluid, it is also rooted in something, either a place like Belgrave Road, or Tottenham or some locality, or a religion or family connections, or cultural connections. This helps provide a sense of ‘belonging’. Bell Hooks in her book ‘Belonging’ reflects upon her home state of Kentucky, America, and her adult cosmopolitan life in New York. She notes that the countryside where she grew up was important for her sense of identity, despite have a clear cosmopolitan outlook in New York.

The nobel prize winner, Amartya Sen in his book, ‘Identity and Violence’, (Sen, 2007) argues people have a multitude of identities, but often policy makers tend to herd people into boxes and in the process they take away the complexity of their identity. For example he argues that the Bangladeshi community in Brick Lane, came from a secular democracy in Bangladesh, a state formed from a bitter war with the Muslim state of Pakistan. However policy makers in Britain treat everyone as ‘Muslims’, and therefore the younger generation have developed a strong Muslim identity, much more stricter than their parents generation. The writings of Bell and Sen therefore offer a different perspectives which takes into account local histories and culture.

In this article, I have tried to examine some of the issues raised by Stuart Hall’s history of black photography which are relevant to black photographers mentioned, and show some of the difficulties in balancing between assessing the artistic object, examining the ethnicity of the artist, and assessing the relationship of practitioners to the art establishment.

As long as black people are marginalised in the UK, and people migrate between nations, people will feel dislocation and have some sort of diasporic identity. There are people who have a global outlook and feel dislocation, and there are also people who feel quite happy living in their locality, but feel dislocation because of marginalisation or a sense of powerless. Where people feel they belong, and where they feel dislocated from will vary.

Hall’s work doesn’t necessarily help us understand this aspect of modern Britain. As Glen Doy’s states ‘if we do not listen to the voices of the creators of black culture, attempting to understand why and how they represent things then we play a part in suppressing active subjects from history and culture’ (Doy, 2000)

Read Part I

_________________________________________________

[1] Val William notes that magazines Creative Camera, CameraWorks and Ten 8 all together as they all were concerned with the notion of Britishness, and people such as Martin Parr and Daniel Meadows specifically moved from the middle class southern homes to photography the changes in northern Britain.

[2] For example the writer Sivanandan wrote, ‘All that melt into air is solid : The Hokum of New Times’, in Sivanandan, 1990 criticizing Hall’s New Ethnicity paper. Hall also wrote in‘From Scarman to Stephen Lawrence’, (1999) about the death of Michael Menson in 1998 who was thrown into the Thames in a race attack as a example of the complacency of the Home Office. Menson was not thrown into the Thames, but died from burns in Enfield. (Student found guilty of Micheal Menson murder, 1999, The Guardian, 21 December)The case was recently highlighted as a serious case and the family was put under surveillance and authorized by the Home Office. (Stephen Lawrence Independent Review, 2014) These mistakes can be compared to his close involvement in the Independent reviews of both the Handsworth Riots (1985) and South riots (1979)

____________________________________________________________________________

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

_____________________________________________________

Jagdish Patel spends his time working as a photographer and writer in London and Nottingham. Previously, he worked in the charity sector with different communities, including spending 10 years as the Assistant Director of human rights charity the Monitoring Group. He is interested in using photography as a research tool to explore the relationship between place, belonging and identity. The territory covered when we think about this can be vast, covering the issues of ecology, our relationship to land and land ownership, equality and human rights, migration, the politics of race and class, and the act of memory and remembering. He continues to work commercially and manage Saffron Moon Photography. He also co-founded the Nottingham Photographers’ Hub, a social enterprise which helps vulnerable communities through photography. Find him on Twitter @jagdish__patel

_____________________________________________________________

Media Diversified is a 100% reader-funded, non-profit organisation. Every donation is of great help and goes directly towards sustaining our organisation.