by Karen Williams Follow @redrustin

Coolie connotes somebody who performs thankless, backbreaking physical labour. The word is often explained as being part of the indentured labour system that followed the abolition of slavery in the 1800s, particularly gaining popularity in the mid- to late-1800s. It is often almost exclusively used in relation to Asian labourers, especially Indian and Chinese people.

In South Africa (and parts of the Caribbean and the Pacific islands) the word is laden with history and is a racially pejorative term to refer to an Indian person. Yet, a number of western academics of Indian descent (often living in the West) have used the term coolie as a descriptive term denuded of history and racial value. This includes suggestions by academics that “coolitude” needs to be celebrated and reclaimed. Since ‘coolie’ is completely associated with Asian indenture, it has historically provided the line between the enslaved African and the indentured (and by implication, un-enslavable) Asian.

For academics and many others it is an archaic, slightly insulting word; in the places where there were ‘coolies’, it is a term of hatred and denigration. Years ago I stopped short when reading an interview with scholar Edward Said, where he said that a group of people were ‘basically coolies’, wanting to signify that the people in question were exploited.[1]

Yet I have come across no source where Indian and Chinese people who were indentured have used the word as the preferred term for themselves – at the time of indenture. Even more than a century after the start of large-scale Asian indenture, the original pejorative context and value of the word remains.

‘Coolie’ is associated with use in the English language, derived from the particular period of British empire-building and colonial entrenchment. Theories to its origins vary. One suggestion is that ‘coolie’ entered into popular lexicon to describe largely Indian (but also Chinese) indentured labourers who were contracted in areas where enslaved people had recently been emancipated, particularly in the British colonies but also encompassing the Caribbean and the United States. The Asian labourers were usually contracted for specific periods of time to replace the free labour that was previously provided by enslaved people in those areas.

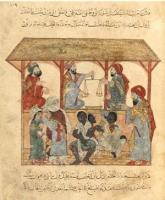

This in itself does not give a complete picture of the last years of slavery, particularly in the British colonies. From the date of emancipation (1834), enslaved people still had to serve a four-year apprenticeship to the people who had previously owned them. When Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807 (i.e the transnational shipping of slaves and open markets), British ships would often raid other European, Arab and Middle Eastern slave vessels to free the slaves onboard. The captives, known as Prize Negroes, were sent to the British colonies, where they were “apprenticed” for periods of up to fourteen years. The apprenticeships mirrored the geographical areas and industries that were developed through unpaid labour. Historian Richard Gott notes the scores of people sent to Cuba under this system of apprenticeship, remarking that the “indenture” was a way to essentially prolong their enslavement and to provide free labour.[2]

Yet the use of the word goes back much further in history, and coolie is not only used in English. Theories to the word’s etymology included it as possibly being derived from the Turkish words for slave, köle as well as qul/kul.[3]There is also speculation that the word is derived from a (peasant) group in western India, the Kolis,[4] or that it originates from the Tamil word for wages, kuli.[5]

The most benign definition of the word is that it refers to a hired labourer[6], or a porter, and during South African slavery (1652-1838), coolie was also used to mean a porter or stevedore.

Although it has fallen out of common, everyday use, the word is also present in both German[7] and Dutch. In Dutch, koelie (with the same pronunciation as in English) refers to labour that is backbreaking, humiliating and monotonous.[8] The Wikipedia entry for the word also mentions that the word originates with very low-skilled Asian labour, dating from slavery. Kuli is also present in Danish, meaning backbreaking, very low-paid work.

Even in the United States, for more than a century it has been a derogatory word for south and east Asian people, and had been used to refer to low-wage, immigrant labourers. The term was still in used in the American military during the Vietnam war, when ‘coolie’ referred to Asian farmers and labourers working in the American areas.[9] American designers also used coolie as a designation for Asian-inspired clothing, including terms like coolie pajamas, coolie hats and coolie coats.[10] In the 1950s, American baseball manager, Branch Rickey (who hired Jackie Robinson as the first black player in Major League baseball), was accused of paying players “coolie wages”[11].

This is crucial in tracing the history of ‘coolie’: although associated with indentured labour, in fact the word already had common currency centuries before and was widely used during slavery. The Dutch, German and Danish connections are critical since all of these nations had long histories as enslaving and slave trading nations: by the 1600s, all three these countries already had very extensive slavery concerns in Africa.[12]

Furthermore, the word had other applications during South African slavery. “Koeliegeld” (coolie money) was the money that enslaved people were allowed to earn by working for people other than their enslavers. A portion of the money went to the owners – and it was often a way for enslavers to make a profit out of owning other people. (In the film, 12 Years a Slave, Solomon Northup is regularly hired out in a similar arrangement.)

The institution of coolie money was critical in South Africa for enslaved people, and there are numerous instances of enslaved people being able to buy their freedom from the coolie money.

In 1799, a Persian traveller Abu Talib ibn Muhammed Khan[13] (also known as Mirza Abu Taleb Khan), gave a valuable account of the use of coolie money in South African slavery. He is also very interesting because he was fêted by the upper echelons of white South African society while there, but being Muslim and not white, he comfortably crossed to the Free Black side as well, and he went to live with a Muslim landlord in Cape Town (probably a Free Black man).

“If a slave understands any trade, they permit him to work for other people, but oblige him to pay from one to four (Rix)dollars a day, according to his abilities, for such indulgence. The daughters of these slaves who are handsome they keep for their own use, but the ugly ones are either sold, or obliged to work with their fathers. Should a slave perchance save sufficient money to purchase his freedom, they cause him to pay a great price for it, and throw many other obstacles in his way.

I saw a tailor, who was married, and had four children; he was then forty years of age, and had, by great industry and economy, purchased the freedom of himself and his wife; but the children still continued as slaves[14]. One of them, a fine youth, was sold to another master, and carried away to some distant land: the eldest girl was in the service of her master; and the two youngest were suffered to remain with their parents until they should gain sufficient strength to be employed.[15]

The word comes up again after the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) with the settlement of Afrikaner families from South Africa in Kenya and Tanzania in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Accounts of the settlers regularly refer to Indian people in east Africa as “koelies”, with the local currency, the rupee, referred to as “koeliegeld” (coolie money)[16].

In the United States, in particular, it is telling how the term was not only descriptive of Asian labour, but was the impetus for highly racialised legislation. President Abraham Lincoln signed “anti-coolie” legislation in 1862 that banned American citizens from owning ships transporting the bonded labour. This was during the American civil war, and still well within the ambit of slavery. In 1862 California introduced what was colloquially termed an “anti-coolie tax” called the Chinese Police Tax[17], reportedly to “protect free white labor(sic) against competition with Chinese coolie labor(sic), and to discourage the immigration of the Chinese into the State of California”. It also levied a tax on Chinese people.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese workers from the United States and California also enacted anti-Asian legislation in its own ‘anti-coolie’ laws. American trades union leaders wanted barriers to large-scale working class Asian immigration. In 1906, after debate, President Theodore Roosevelt allowed Asian workers to construct the Panama Canal, a year after he had talked about the “coolie class” in his State of the Union address. Asian indentured labourers worked on Hawaii’s sugar plantations in 1920, despite strong trade union opposition to Asian workers.[18]

In the Caribbean, indentured labour did not start with the Asian labourers. In the 17th century, Europeans were the first wave of indentured servants to the Caribbean, representing what Trinidad’s independence leader, Eric Williams, terms white immigration and labour that “was not free but involuntary”[19]. The conditions surrounding white labour in the Caribbean are important: too often the fact of white labour has been used to spur historical untruths, particularly about “Irish enslavement”.

White indentured servants usually served a period of three years, but it could be for as long as five years. White servants were free after their stipulated time, and were generally granted a plot of land. The system was open to abuse, and bad treatment and kidnap (especially from Bristol) was not unheard of.

Williams mentions that between 1838-1924, an estimated half a million Indian indentured workers came to the Caribbean, along with Chinese workers and other Asian people.[20]

“The Asian labourer was not a slave. He was a freeman, and he came to the Caribbean on contract, generally for five years. Thus the Caribbean, which had in the seventeenth century sought in the white indentured servant a substitute for the indigenous Amerindian, turned in the nineteenth to indentured Asians as a substitute for the African slave who had supplanted the white indentured servant.”[21]

The long-term consequences of slavery and indenture have irrevocably shaped the societies in which it took place. Guyanese political scholar Walter Rodney cited that, “Indenture, unlike slavery, was constantly producing free citizens in large numbers”. Rodney had identified the indentured labour system as one of the common practices of exploitation that African and Indian Guyanese fought against, until it ended.

The conception of change which the Guyanese workers entertained during the war was by no means restricted to the exploration of the interior. On a number of vital fronts they were prepared to wage a struggle against the forces of oppression. One of their most crucial battles was for an end to indentured immigration, and subsequently for the prevention of exploitation of the same ilk.

Part of the emotive force of the word coolie is that it evokes (Indian) degradation, coupled with silent passivity. Rodney locates indenture as a site of political struggle and part of a larger fight for freedom. The political resistance to indenture is also invoked by the thousands of Chinese labourers brought in to work on Cuba’s sugar estates, working alongside the enslaved Africans. The Chinese indentured labourers were also seen as the backbone of various independence movements and supporters of freedom struggles on the islands – and not passive toilers under indenture.

At the same time, indenture was no guarantee for social and economic advancement: one of the more instructive lessons of my childhood was taking shortcuts through the sugar plantations on South Africa’s east coast, and deep inside the farms finding tiny chalkwhite stone houses housing multiple generations of (usually Tamil) Indian workers in the dark airless hovels. These families had likely lived there since their indentured ancestors arrived more than a century before, and it was very unlikely that their next generation would get off that plantation anytime soon.

In a final historical twist, the push for sugar production and its need for labour in the 1800s might have been the consequences of the defeat of slavery in Haiti. Saint-Domingue (as pre-independence Haiti was called) was the major global sugar producer, accounting for a major share of European sugar markets. World markets were affected by the overthrow of slavery on the island during the 1791-1804 revolution. Besides being the world’s largest sugar producer, Haiti also supplied smaller amounts of coffee, indigo, cotton and other goods to the world market. In the early 1700s, Saint-Domingue had wiped out the British competition and was well on the way to taking over world markets through the quality and cheapness of its product.[22] The Haitian revolution fundamentally changed the supply of sugar to world, providing the impetus for increased production in other parts of the world to fill the gap.

References

Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience: Ed. Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. ,Civitas Books 1999

Children of Bondage – Robert C.-H. Shell, Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg

Collins – Pocket Turkish Dictionary: Harper Collins Publishers (First Edition), 2011, Glasgow, Great Britain

Cuba: A new history – Richard Gott, Yale Nota Bene/Yale University Press (New Haven and London) 2005

Echoes of Slavery – Jackie Loos, David Phillips Publishers

Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and his struggle with India, Josef Lelyveld, Vintage Books, (April) 2012, New York

The Boers in East Africa: Ethnicity and Identity – Brian M. du Toit, Praeger Publishers

From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean: Eric Williams, Andre Deutsch (London) 2003

Masses in Action – Walter Rodney (first accessed 25/06/16)

[1]It will be interesting to look at whether the word is used mainly by people who live and work in fairly privileged settings in Europe and north America, as opposed to those academic descendants who live and work in the Third World – and where the real value of the word still retains its resonance.

[2] Gott p.60

[3]Collins Pocket Turkish Dictionary

[4] Lelyveld p. 9

[5] Ibid

[6]Gandhi, L: A History Of Indentured Labor Gives ‘Coolie’ Its Sting, November 25, 2013

[7] Discussions with Ulli Klecz 09 May 2015, Cape Town

[9] A history of indentured labor gives coolie its sting

[10] Ibid

[12]While the Dutch, through its Dutch East India and Dutch West India companies are well documented, the early German enslaving history through its Brandenburg African Company. Accounts of slavery on Africa’s east coast and in South Africa regularly mention Danish slaving ships.

[13] He is referred to as Persian (born in India) even though his name is Arabic.

[14] All children born to enslaved mothers would automatically be enslaved at birth.

[15] Loos, p. 6

[16] Du Toit p.90

[18] Ibid

[19] Williams pp 95-6

[20] Williams p. 348

[21] Williams p.351

[22] Williams p.133

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Karen Williams works in media and human rights across Africa and Asia. She was part of the democratic gay rights movement that fought against apartheid in South Africa. She has worked in conflict areas and civil wars across the world and has written extensively on the position of women as victims and perpetrators in the west African and northern Ugandan civil wars.

Indian Ocean Slavery is a series of articles by Karen Williams on the slave trade across the Indian Ocean and its historical and current effects on global populations. Commissioned for our Academic Space, this series sheds light on a little-known but extremely significant period of international history.

Indian Ocean Slavery is a series of articles by Karen Williams on the slave trade across the Indian Ocean and its historical and current effects on global populations. Commissioned for our Academic Space, this series sheds light on a little-known but extremely significant period of international history.

This article was commissioned for our academic experimental space for long form writing curated by Yasmin Gunaratnam. A space for provocative and engaging writing from any academic discipline.

If you enjoyed reading this article, help us continue to provide more! Media Diversified is 100% reader-funded – you can subscribe for as little as £5 per month here or via Patreon here