by Sara Tafakori and Gilda Seddighi Follow @SaraTafakori Follow @GilSedd

‘From the American people to Iranian social media users: if your expert opinions and discussions about the American election have ended, please do shut up for a moment and let us Americans work out what the heck we do now’. This tweet by a presenter of a diasporic Iranian channel[1] shortly after the election result, promptly went viral, travelling from Twitter (considered a more elite platform in Iran), to Telegram, which has skyrocketed in popularity to reach a much broader audience. The tweet satirically acknowledged the flavour of ordinary Iranians’ online engagement with the American election. Iranian social media users have engaged with the outcome of the US presidential contest in quite different ways from Western media commentators.

The presidential election in the US, with all its controversies and burgeoning debates, has come to an end, if not with an outcome the mainstream media would have imagined. One of the striking features of Trump’s victory has been its representation in the Western mainstream media in terms of shock and horror, as a ‘catastrophe’ which seems to have disrupted an otherwise ‘ordinary world’ for their audiences. For these outlets, the election has generally posed questions in the vein of what-will-happen, what-to-expect or how-to-predict-the-future in the face of ‘the end of the West as we know it’. This rendering of unpredictability and uncertainty of a future that is yet to come for the ‘West’, has contrasted markedly with the content and direction of reactions to Trump’s victory in Iranian social media. Nonetheless, whilst Trump’s victory immediately trended across social media platforms worldwide, what has so far attracted attention has been the reactions on Western media platforms.

After the announcement of the result, the dominant image of the election in the Western media remained that of fear and anguish about this ‘apocalyptic’ event. By contrast Iranian platforms were filled with avalanches of commentary in which hysteria over the election of Trump in the mainstream media was picked up and made fun of in streams of witty and satirical comments circulated on social media. What stood out in these responses was their rejection of the narrative of Trump’s victory as a yet-to-unfold catastrophe or a disruption of the ‘normal’. Instead, a flurry of tweets sought to present the uncertainty associated with the US election as a part of a prolonged and endured continuity of social and political insecurity and war in the Middle East in general, and Iran in particular. The tweets speak to the reality that the election of Trump is not only of significance to the American audience for its immediate effects or to Europeans for their economic or military alliances; what has been neglected is precisely its impact on people ‘outside’ the West. For example, there are political, military and economic implications of American politics that have long had consequences for the contemporary politics of the Middle East. This is especially so since the inception of the War on Terror instigated by George W. Bush’s administration in response to the 9/11 attacks.

Here, we have extracted some of the popular comments produced within ‘Farsi Twitter’ and ‘Hyperactive-Farsi Twitter’, two group channels operating on Telegram, which has now become the most popular messaging app for sharing, networking and generating content in Iran and in the diaspora with reportedly over twenty million users. The focus on these two pages is not only for their popularity, but also for their function as platforms, compatible with most mobile phones, iPads and laptops/desktops, which has facilitated the (re)sharing of the perceived best Farsi tweets among a greater variety of users. The administrators select and re-share popular tweets on Farsi Twitter in their channels which enable subscribers to copy, share, and/or forward these accounts to other Telegram users or groups, regardless of whether the recipients are already signed up to the page. The instance below is one of hundreds of thousands of tweeted images and texts reshared on Farsi-Twitter channels during the first day after Trump’s victory. It humorously emphasises that the Trump-induced uncertainty is part of a broader and longer-term uncertainty in the Middle East and not a new phenomenon:

‘One of my colleagues is American. She’s sitting in the corridor crying now. Does it mean that the situation is really this serious or[but] that we [Iranians] have just got so used to it [the bad situation]?’

(Hashtag on Election_US)

In this example, the tone seems flat and descriptive at first, distanced from the colleague’s anguish. This overemphasised flatness of tone alerts us to the sense of a continuum, rather than a sense of the situation as uniquely disturbing. In what becomes a darkly amusing performance the subject insists on being or becoming s/he ‘who does not ‘feel’ any of the singularity of Trump’s election. If anything, there’s a sense of familiarity with the precarity of the given situation. Here, the one who does not ‘feel’ the urgency of the event is surrounded by others’ sentiments of danger. In this situation, the tweeter is the one who demands recognition, to be taken out of the crowd of those feeling the immediacy of the catastrophic Trumpian world. So, a separation occurs as a result of rejection of one’s inclusion in the Western mainstream narrative of apocalypse. It’s a separation dramatised in the image, as we view from afar the sorrow for ‘the end of the world as we know it’.

It is of course the case that a very small percentage of people in the US would be able or likely to read this tweet and reflect on the question it poses. In this sense, the question is mainly directed towards an online community who orient to Iran as ‘home’; but that seems to suit the prevailing emphasis in these tweets on the particularity of Iranian and Middle Eastern experience, as against the presumed universality of American and Western experience. One of the most succinct and sardonic statements of such parallels is a tweet in Arabic, which was also shared on Iranian social media. It points to commonalities of experience and perception across the countries of the region in reaction to the Western media discourse concerning a single, uniquely alarming event. :

‘OK then, the Daesh (IS) thing is ending soon. Prepare yourself!’

This tweet, which was seen over 100,000 times and shared over 4,000 times, positions each recent US president alongside their associated terrorist enemy to suggest fatal connections. It foregrounds the forgotten continuity of disaster for people outside the scope of the Western mainstream media, and rejects the idea of Trump’s victory as a singular catastrophe. The paired pictures, with their captions, create a series of specific connections between particular terrorist or fundamentalist groups, and the US presidents. All smiling, Bill Clinton is paired with the Taliban, George W. Bush with Al Qaeda, Obama with Daesh (IS), and finally, as a prediction of the future-about-to-become-present, Trump is paired with a zombie from a horror movie.

Both sets of phenomena appear, from without, to stand for larger, unstoppable and inscrutable forces in play. They are linked to each other in a manner that is at once enigmatic, and yet traceable. A further deterioration into chaos on one side is mirrored faithfully by deterioration on the other. In this respect it is clear that this Middle Eastern perspective on the US elections, far from making light of Trump’s election, far from merely indulging schadenfreude, partakes of a far more profound and numbed pessimism. This pessimism sees the event as one of many stages – perhaps the last, but who can tell? – in an ongoing catastrophe, not as an unaccountable disruption by a deus ex machina of an otherwise progressive forward movement.

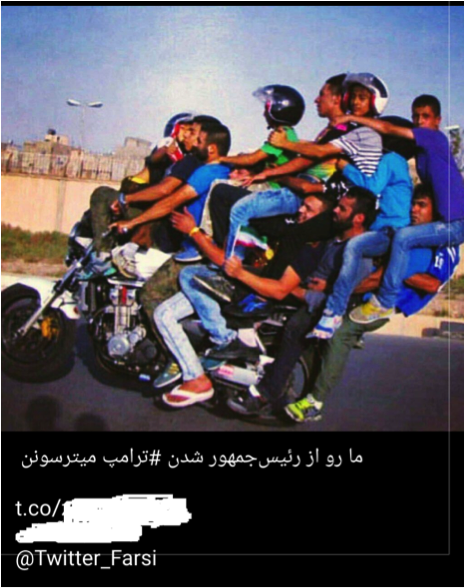

The emphasis of such tweets on the neglected mode of the continuity of the state of precarity in everyday life is not always accompanied by explicit reference to American political and military interventions in the region, but commonly bears upon the implications of such actions within what can be called ‘home politics’. Through making fun of the insecurity surrounding lives branded as ‘Middle Eastern’, this common Iranian positioning – that the present is merely part of a continuum of catastrophe – stands as opposed to the positioning of the Western media in the aftermath of Trump’s victory. While the latter indicates concern about a future ‘loss’ of ‘progress’ achieved up to ‘now’ – presumably during the Obama presidency – Iranians have tended to generate content which questions the assumption about the uniquely precarious nature of the present moment that is embedded within this anxiety. The tweeted image and caption below best illustrate this point:

‘They [the West] are scaring us [Iranians] about Trump’s presidency [?]”

In the above tweet, one sees more people than one could imagine, including children, riding on a motorbike. Whilst the image wittily mediates a sense of insecurity and danger, it is not only the contradiction between the depiction of how ‘we’ ride on a motorbike, and the presumed high Western standards of road safety that makes this picture humorous . It is also the caption – ‘They are scaring us about Trump’s presidency [?]’ – which suggests that this comedic exaggeration of endemic uncertainty actually speaks the ‘truth’ of everyday life – for Us. If anything, the mocking tone conveys familiarity with a state of precarity, which They can never know. The tweet makes fun of the sense of interruption in normal social and political functioning associated with Trump. Here, then, simultaneously with the rejection of inclusion in the Western narrative, another kind of inclusion is brought to the fore, involving self-recognition of a common Iranian and Middle Eastern experience.

What is striking, as we have said, is that the humorous mediation of the U.S. election on Farsi online platforms presents anguish and fear as already existing components of life in the Middle East in general and Iran in particular, rather than subjecting its audience to speculation and prediction about a newly uncertain ‘future’. The language of sarcasm, implicitly conveying sentiments of pain and distress, dominates the outpouring of Farsi messages on Twitter and Telegram as the two popular and widely used social media platforms. This sardonic mediation takes ‘home’ politics and everyday life as its point of departure in reflecting on the US election. In their tendency to target the apocalyptic features of the mainstream media narrative through narrating the everydayness of ‘home’, these tweets paradoxically emphasise the traumatic impact of the intersection of home politics and international politics in an era marked by the impact of sanctions and repeated military interventions.

In rejecting the mourning that is claimed to be the result of Trump’s volcanic interruption of America’s liberal and progressive self-image, the over-excited Iranian social media commentary disturbs the exceptionalism that has been at the heart of recent Western media coverage. Iranian tweeters have affectively and playfully thrown into question the longstanding constructed distinctions through and by which the West defines itself against the rest of the world.

[1] Hosting a show on the very popular private and cable ‘Farsi1 channel’ operating outside Iran, Sina Valliallah is a familiar face in Iranian households.

This article was commissioned and edited by Yasmin Gunaratnam for our academic experimental space. A space for provocative and engaging writing from any academic discipline.

All work published on Media Diversified is the intellectual property of its writers. Please do not reproduce, republish or repost any content from this site without express written permission from Media Diversified. For further information, please see our reposting guidelines.

Sara Tafakori is a PhD candidate at the University of Manchester researching the emotional politics of sanctions on Iran. In her pre-migratory life as a journalist and reporter in Iran, her commentaries and articles featured in national newspapers and journals. Her interests include migration, gender and sexuality, Western mainstream media, the intersection of social media and the politics of belonging and nationalism. She tweets at @SaraTafakori.

Gilda Seddighi is a PhD candidate at the Center for Women and Gender Research and the Department of Information and Media Studies at the University of Bergen, Norway. Her PhD research focuses on social media users’ expressions of emotion in the production of grievable lives in the aftermath of Iranian Presidential Election of 2009. She tweets at @GilSedd.