Continuing his series on Anti-Blackness in South Asia, Dhruva Balram discusses violent attacks on Black Africans in India and how the root of the issue is the anti-Blackness in India that has existed for centuries

Read the other articles in the series

In January of 2016, in Bengaluru, India, a Sudanese national ran his car over a 35-year-old Indian woman, killing her. A mob gathered. They burnt his car as he fled. A 21-year-old Tanzanian woman who was driving by along with three friends was stopped. She was dragged out of the car, stripped, beaten, and paraded around, eventually being pushed out of a slow-moving bus passing by which she tried to board to escape. Her friends were also beaten up. Five months later, a Nigerian student in Hyderabad was allegedly beaten over a parking dispute. Two days after that, on 22 May 2016, 29-year-old Masonda Ketada Olivier was hailing an auto rickshaw after a party in New Delhi. He got into an altercation with individuals who insisted that they are allowed to board ahead of him. Olivier was subsequently beaten to death.

The death of Olivier prompted a long overdue and much-needed discussion between heads of state in Africa and their international relations with India. There were talks of a crisis. It was the latest and most high-profile incident of racism yet by Indian citizens towards African nationals. With Africa Day looming in New Delhi, several nations threatened to boycott the official Indian government celebrations. This prompted interventions from the Indian government and assurances that the safety of African nationals in India became a priority. In March of 2017, less than a year after Olivier’s death, a mob of Indian nationals in Greater Noida beat students from the Association of African students in India. They used metal rods, garbage bins, and other miscellaneous objects that could be used for violence. Over 100 people in New Delhi protested that any Africans living in rented homes left immediately.

“The numbers of people enslaved and the exact length of the trans-Indian slave trade have not been definitively established, but historians believe that it preceded the transatlantic enslavement by centuries. Even though it is largely ignored as the international slave trade, examples of its impact abound”

In response to the mob’s public assault on African students, External Affairs Ministers Sushma Swaraj said, “Before the inquiry is completed, please do not say it is driven by racial discrimination. We do not immediately say that attacks in the United States are due to racial discrimination.” There is a continual mindset in South Asia where we believe conditioned actions, our societal beliefs and misconceptions are not racist. Only now do we seem to even be discussing our inherently internalised colourism and racism. But, all we need to do is look back to understand the present.

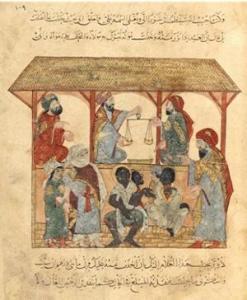

History in South Asia is rife with anti-Blackness. In a article published by Media Diversified in 2016, historians stated that they believe that the Indian Ocean slave trade preceded the transatlantic one. “The numbers of people enslaved and the exact length of the trans-Indian slave trade have not been definitively established, but historians believe that it preceded the transatlantic enslavement by centuries. Even though it is largely ignored as the international slave trade, examples of its impact abound.”

The article dissects how even “words like “coolie” and “kaffir”, often associated with the Asian indentured labour system prevalent under later European colonialism, had roots and common usage in the periods of Indian Ocean slavery from the 1600s onwards.” Despite having suffered at the hands of colonisation, history in South Asia is intertwined with violence towards Black bodies. The subjugation of Black bodies has been intrinsically linked with South Asian oppression reflecting colonial, anti-Blackness in our communities. And it doesn’t help that India’s most famous individual, Mohandas Gandhi, has a racist past.

Legendary Indian freedom fighter and icon for peaceful protests everywhere Mohandas Gandhi used the terms “Coolie” and “kaffir” interchangeably. In 1893, Gandhi wrote to the Natal parliament saying that a “general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are a little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa.”

Dr Ọbádélé Bakari Kambon, a research fellow at the University of Ghana, and the man who initiated the #GandhiMustFall campaign is understandably upset. “What people did not see is that he was against Black people,” he said when discussing Mohandas Gandhi. “He was an Indo-Aryan, upper-caste Hindu; he was always fighting for upper-caste Hindus and he was never fighting for Black people there in India.” Dr Kambon has successfully fought to remove a statue of Mohandas Gandhi outside the University campus. He has also spoken on the topic at length, telling the Caravan, “From 1893 to 1913, he was always saying — these Kaffirs, we don’t want to work with them; even when it comes to striking, we are not trying to strike alongside these Kaffirs”.

Ọbádélé Bakari Kambon, research fellow at the University of Ghana

Gandhi stated that “black people are one degree removed from animals” and when he was in jail, he is quoted as saying they “live like animals”. Gandhi, in 1904, wrote to a health officer in Johannesburg that the council “must withdraw Kaffirs” from an unsanitary slum called the “Coolie Location” where a large number of Africans lived alongside Indians. “About the mixing of the Kaffirs with the Indians, I must confess I feel most strongly.” When Durban was hit by a plague in 1905, Gandhi wrote that the problem would persist as long as Indians and Africans were being “herded together indiscriminately at the hospital.” As Dr Kambon explains, “In 1906, according to his autobiography, he had this huge epiphany. (Gandhi took a vow of celibacy and stated that he learnt the error of his ways). But some of the worst things that he said and did after that so-called vow.”

I always thought of Gandhi as our saviour, the person that brought independence to India. What I (and the rest of the country) is never taught is that he only gave a sliver of people independence: educated, upper-caste individuals while continuing to oppress others, namely darker-skinned individuals. As evidenced by recent beatings, riots and deaths, the treatment of African nationals in India is a particular problem. But as with any other anti-blackness and colourism it works within a troubling societal context.

“Having lived in India for over 5 years, Lawrence has seen the violence first-hand. Rather than dwelling on the negatives that come with anti-Blackness, the systemic and entrenched racism that he and others have to face, Lawrence wants to change the narrative of what it means to be dark-skinned, to be Black in India”

Dr Shingi Mtero, of Rhodes University, wants to see a more just society where we can learn from these mistakes: “Many people across the world believe that Africa is a single country, that Africans live in huts, and would not be able to develop if it were not for the assistance of European powers; these problematic, racist stereotypes can only be deconstructed by exposure and awareness of the reality of Africa” she wrote in an email. “So until South Asians travel to African countries, interact with different types of African people, and are presented with different images of African countries in the media – their perceptions will remain the same.”

Ezeugo Nnamdi Lawrence, the director of African affairs at the Indian Institute of Governance and Leadership, echoed the sentiment stating, “Certain mainstream tools including media and local NGOs have a role to play along with the government in sensitising the misconstrued perceptions towards my people.” Having lived in India for over 5 years, Lawrence has seen the violence first-hand. Rather than dwelling on the negatives that come with anti-Blackness, the systemic and entrenched racism that he and others have to face, Lawrence wants to change the narrative of what it means to be dark-skinned, to be Black in India.

“Building progressivism in the network of African students through the Association of African students in India (AASI) which is fast becoming a Pan-Indian African students sponsored organisation would not have been possible if we had not focused on positivities where there are adversaries that were supposed to negate such success,” he wrote in an email. “We have been able to set a standard and representation of the African at all levels from grassroots to the international community,” he added. “We have come to the realisation that Africa can be made greater by Africans and having experienced the love and hate from others is enough motivation. Personally pushing for the actualisation of the Pan-African Renaissance and a Global South relationship of mutuality and respect has been very well received and this no doubt will further strengthen the future ties between Africa and India.”

Ezeugo Nnamdi Lawrence, director of African affairs at the Indian Institute of Governance and Leadership

Anti-Blackness may be a scourge, and the subjugation of violence against Black bodies is the end result of it, but it is a complex web that creates these issues. Bollywood’s depiction of African people; our own diaspora’s co-option and exploitation of Black culture; and the horrific caste-based violence that continues to play out on a daily basis in South Asia. There are however ways that South Asians can start to repair our views towards darker-skinned and African people.

For Lawrence, it starts with education. “African history, languages, and culture need to be inculcated in the curricula of schools at various levels so that the knowledge of African can be shared with the younger ones.” There also needs to be education on how diverse the continent of Africa is within India and cultural exchanges between the countries will break down preconceived notions. For wealthy Indians there is always travel abroad to Europe and the USA, but rarely any to anywhere in Africa. Media companies also have a huge role to play in the depiction of African people in India.

Evidenced by an earlier piece on Bollywood I wrote and further cemented by mass media’s portrayal of Black bodies, negative stories about Africans cannot be the only thing we see and read about. Like South Asians complain that white-centric media paints us with a single brush, we need to ensure that we don’t do the same to other cultures. As Lawrence puts it, “Africans are no lesser humans and should not be treated any different, we know who we are, and we know how much we have contributed to the growth of humanity.”

Dhruva Balram is an Indian-Canadian freelance journalist exploring interests in pop culture, music, communities, societal issues, and South Asian identity, Dhruva is currently based in London, UK.

Read the other articles in the series

Follow @dhruvabalramIf you enjoyed reading this article, help us continue to provide more! Media Diversified is 100% reader-funded you can support us via Patreon here or subscribe for as little as £5 per month here